In the search for ways to reform the flawed current welfare system, some form of basic income guarantee has received more attention. My colleague Michael Tanner has reviewed some of the related pros and cons, but most of those studies confined themselves to the immediate to short-run impact on work, leaving many important questions unanswered. A new paper from Daniel Price co-authored with Jae Song offers one of the first studies to analyze the long-term impact of cash assistance from the negative income experiments that took place last century. Their findings suggest “unintended and unexpected long-term consequences for recipients” and ambiguous effects on their children. It’s important to understand these effects when considering ways to try to address the many problems with the troubled status quo.

In the 1960s and 1970s, when interest in a basic income was at a peak, there were large-scale evaluations of the idea of unconditional cash transfers in the Seattle and Denver Income Maintenance Experiments (SIME and DIME, respectively). Recipients were given an unconditional cash transfer that was phased out as earned income rose, for a period of either three or five years. There were a host of studies analyzing the impact on poverty, work impact, and other measures, but these were more focused on the short-term effects.

This paper is so important because, as the authors explain, “virtually no other research has been conducted on the impact of cash assistance—or, indeed, any other type of government assistance—on beneficiaries themselves long after the assistance has ended.” Some of this is due to data limitations, and the authors are able to combine SIME/DIME date with administrative records from the Social Security Administration and the Washington State Department of Health.

The impact on poverty and material hardship is more straightforward and easier to measure, but some of the effects on work effort and other measures are still not as well understood. In this paper the authors find some evidence that participation did seem to have an impact on both work and earnings later in life for adult recipients. Participation reduced the probability a worker was active in any given year by 3.3 percentage points, and decreased average earnings by $1,800 (about 7.4 percent of mean annual earnings).

Another way to put it: for each $1 in additional government transfers, the authors find that an individual’s discounted lifetime earnings are $4.50 lower.

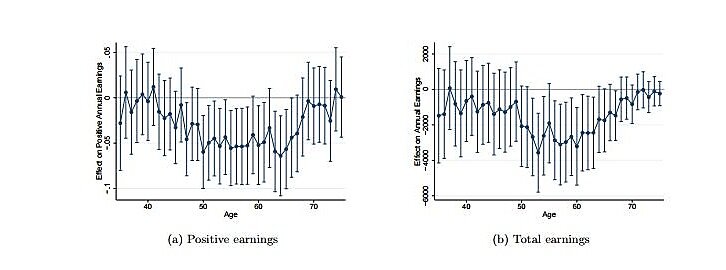

Impact on Propensity to Work and Earnings for Parents, by Age

Source: Price and Song (2016).

Notes: Each data point represents the estimate and 95% confidence interval of the coefficient on a dummy for financial treatment status in one regression, limiting the sample to data from individuals when they are a certain age. Earnings variables are based on one observation per year for all years between 1978 and 2013.

These effects are mostly concentrated towards the end of a person’s working life between ages 50 and 60. Song and Price suggest three channels that might explain this pattern of some reduced work effort during the experiment, minimal effect immediately after, and then larger effects decades later as former participants near retirement age. If these adults saved some of those transfers, they might be more able to reduce work hours or retire earlier. If they worked less, the wages they were able to command might be lower because they had less time to develop their skills and human capital. Or it could change their preferences, by making them place more importance on leisure time that they were able to increase during the experiment.

This could have significant implications for discussions about how to address some of the worst shortcomings of the current welfare system. The substantial reductions in earnings and work effort should be incorporated into how we think about the ramifications of these programs.

The parents weren’t the only ones affected by these programs, their children were too. There is a wide range of plausible effects on the children: parental benefit receipt could the probability of their children also receiving benefits and reducing work effort. It’s also possible that the additional income from transfers will allow parents to invest more in their children and increase their human capital and earning potential later in life.

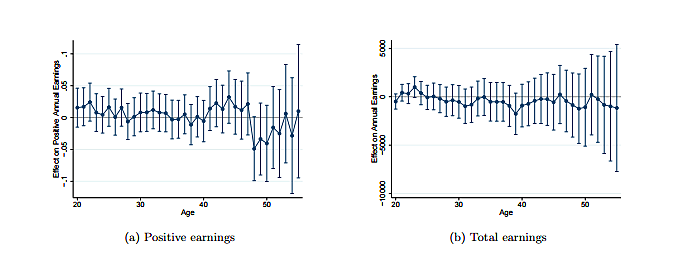

In this long-term analysis, the authors find “little evidence of an effect on children for any variable studied.” These include probability of applying for disability, propensity to work, and impact on annual earned income. The results for children should be considered with caution due to the number of tests that they run on child outcomes. These findings cut both ways, in a sense: it doesn’t seem to be the case that parents getting sizable cash assistance during the program duration discouraged work for their children, but there also weren’t substantial positive effects on children’s eventual work outcomes due to more investment or other effects of having higher household income. In their words:

Taken as a whole, our results suggest that cash assistance could have unintended and unexpected long-term consequences for recipients without significantly improving their children’s earning potential or decreasing their propensity to use government benefits. On the other hand, in our context, we can rule out the idea that cash assistance creates a welfare culture that decreases children’s earned incomes or their dependency on disability benefits by a large amount.

Impact on Propensity to Work and Earnings for Children, by Age

Source: Price and Song (2016).

Notes: Data from Denver families only. Each data point represents the estimate and 95% confidence interval of the coefficient on a dummy for financial treatment status in one regression, limiting the sample to data from individuals when they are a certain age. Earnings variables are based on one observation per year for all years between 1978 and 2013.

These findings highlight why experiments with rigorous evaluation are so important because there are significant effects that aren’t yet fully understood. Studies like this can produce surprising results and new evidence that forces policymakers and researchers to update how they think about these issues. There are some aspects of cash assistance and a basic income guarantee that the authors can’t analyze here, for example these experiments treated a small share of people within their respective cities and the impact of a community wide experiment could be significantly different. The one thing we do know is that much more research in this sphere is needed to understand the limitations and unintended consequences involved.