General David Petraeus and Brookings Fellow Michael O’Hanlon recently took to the Wall Street Journal to assure the American people that, despite sequestration, there is no military readiness crisis. A few days later, Thomas Donnelly and Roger Zakheim published a rebuttal in the National Review claiming that the challenges of too few personnel and aging, overextended equipment induced a “wasting disease.” They alleged that the size of the defense budget was a misleading statistic without context.

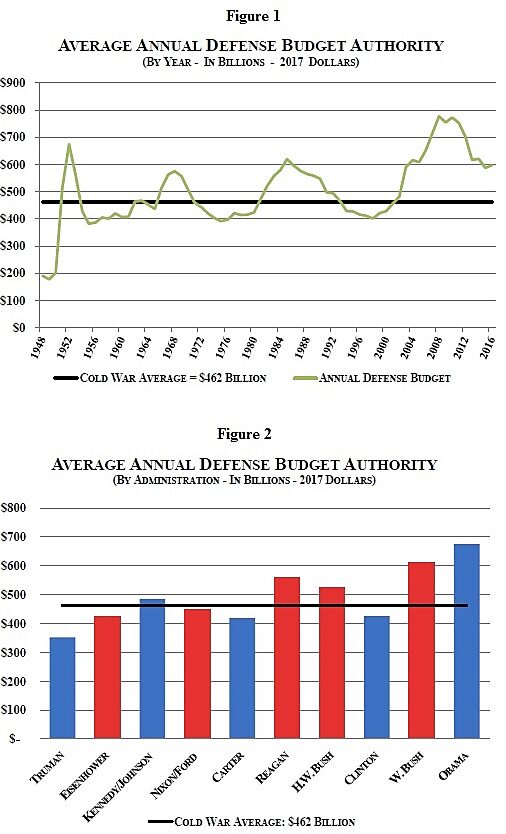

So, here’s some context. After a rapid demobilization following World War II, the United States slowly rebuilt its forces to balance against the Soviet Union. Spending remained far above pre-World War II levels for the remainder of the decades-long conflict, and ever since. The Pentagon budget averaged $462 billion from 1948–1990 (in FY2017 dollars), with notable spikes for the Korean War, Vietnam War, and the Reagan build up in the 1980’s (See Figure 1). With the end of the Cold War, we see a fairly steep decline in military spending during the H.W. Bush and Clinton years. In the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the reductions of the 90s gave way to much larger Pentagon budgets, as the George W. Bush administration embarked on the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Defense spending during the early years of the Obama administration remained above $750 billion as the president ramped up the war in Afghanistan while working to end the war in Iraq. In constant, 2017 dollars, annual Pentagon spending during Bush 43’s eight years in office averaged $612 billion; under Obama, the average is $675 billion (See Figure 2).

One side-note regarding the grouping by presidential administration: Taken alone, the picture can be misleading, in that Reagan inherited Carter’s final budget, Clinton inherited H.W. Bush’s, etc. And, besides, Congress, not any single president, makes the final decision on what the government spends. It is also true, however, that Congress has typically deferred to presidential preferences, particularly when it comes to military spending. Had Clinton wanted more, he likely would have gotten it (and did, starting in 1999); Obama, meanwhile, could have requested less (and, eventually, did). Those variations within four- or eight-year terms get lost in a graph that lumps all the years together in one fat bar for each president.

With respect to whether current spending levels are far too low, far too high, or somewhere in between, the Budget Control Act (BCA) of 2011 and its threat of sequestration tried to rein in spending on both defense and non-defense discretionary spending, but has been only partly successful. Congress has found ways around the defense caps, in part by funneling extra money to the base budget through the Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) account, which is exempted under the BCA. And, under the BCA caps revised late last year, estimated military spending would average at least $551 billion from 2017 to 2021 (.pdf, see page 15) — and likely more than that if Congress doesn’t kick its OCO addiction. That’s 28 percent higher than in 2000, and 19 percent higher than the Cold War average.

In short, if there is a readiness gap, it’s not due to lack of funding. The BCA, by itself, has not resulted in significant cuts in military spending. In inflation-adjusted dollars, we spend more today than during the average Cold War year, and more than we spent at the start of the War on Terror. It would appear that we are mostly getting less “bang for our buck” than during previous generations.

Defense acquisition and compensation reform would help the Department of Defense to better channel scarce resources to its priorities. Similarly, the Pentagon has repeatedly requested the authority to close unneeded military bases, which a short-sighted Congress refuses to allow. But such common-sense reforms, that are supported by a broad bipartisan coalition of defense budget experts (including O’Hanlon, Donnelly and Zakheim), would not be enough to close the means/ends gap.

We also need to revisit the military’s requirements, which are a function of the nation’s overly ambitious grand strategy. We should shift away from primacy, which expects the U.S. military to meet all dangers, in all places, at all times, and instead pursue a strategy that expects other countries to address urgent threats to their security before they become threats to their region, or the globe. Restraining U.S. policymakers’ impulse to use the U.S. military might induce greater self-reliance on the part of U.S. allies, but, as important, it would reduce the likelihood that the United States will become involved in foreign conflicts that sap our strength and undermine our values.

Graphs prepared by Caroline Dorminey and James Knupp

Source: FY2017 Green Book, includes OCO funding