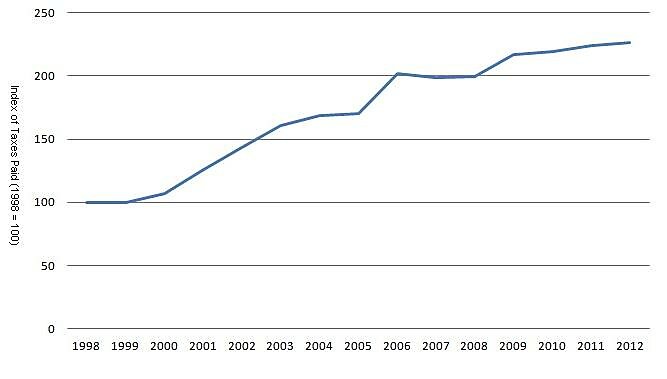

When I read in my local paper, the Sun Gazette (published in Washington’s Virginia suburbs), that the Arlington County Board was planning to raise property taxes, I prepared the chart below. It shows how my own property taxes have risen since I bought a house in 1997 (with my first tax bill, in 1998, set at 100).

I had the following letter published this week in the Sun Gazette:

[Arlington] County Board members are discussing raising the real estate tax rate by 5 cents. The Sun Gazette on Feb. 28 published a chart showing that the proposed rate was actually higher in 2000 and 2001. But what you didn’t show was the soaring level of real estate assessments. Property taxes are much higher than they were a decade ago. My first Arlington tax bill was in 1998. My 2012 bill was more than double the 1998 rate–about a 127-percent increase. I think that’s true for most Arlington homeowners. It’s not easy to find past budgets on the county government’s Web site, but I would assume that the county’s revenue has gone up approximately as much. So Arlington isn’t hurting for revenue; it’s just itching to raise spending even faster than tax revenue rises. The Sun Gazette quoted County Board member Libby Garvey saying that a 5‑cent tax hike is “a very good compromise.” Not for taxpayers, it isn’t.

This pattern happens in many states and localities, of course: they spend money freely in good times, then run into trouble when the economy or the housing boom slows down. As Chris Edwards told a reporter in 2009, states during the preceding years had “repeated the same mistakes they made in the late ’90s, assuming the good times were going to last forever.” And when the money stops rolling in, they don’t want to cut back–so they decide to raise taxes to keep their revenue and spending at the high levels they reached during the boom.