As The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, and several other news outlets reported recently, although it has managed to avoid setting off another taper tantrum like that of 2013, the Fed is having a bad case of unwind jitters, thanks to unanticipated tightening in the market for fed funds.

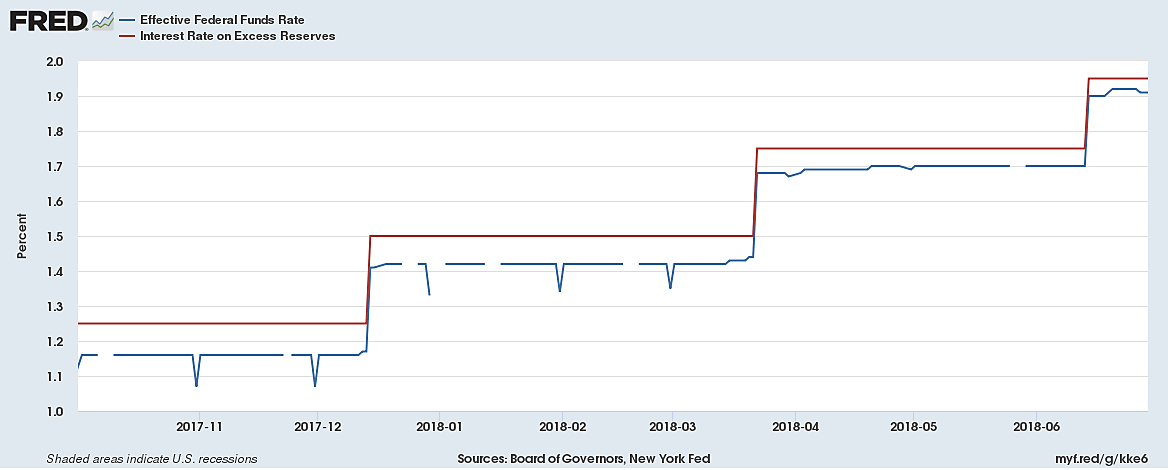

That tightening has manifested itself in a considerable narrowing, since the Fed began unwinding in late October 2017, of the gap between the Fed’s IOER rate and the “effective federal funds” (EFF) rate — meaning the actual rate banks have had to pay other banks, or GSEs with Fed accounts, for unsecured, overnight funds.

In effect the narrowing IOER-EFF gap means that the Fed’s recent IOER rate hikes have ended up being more potent than was expected. As a step toward addressing the problem, the FOMC at its last meeting decided to redefine its funds rate target range upper limit. Now, instead of being equal to the going IOER rate, the upper limit is defined as the IOER rate plus 5 basis points. By itself the new definition is the sheerest of window dressings. But because the Fed, which had been contemplating raising its IOER rate to 200 basis points, could now raise it to just 195 basis points, whilst still sticking to its original rate move, as defined by the upper and lower bounds of its rate target range, the change marked a slight retreat from the Fed’s original tightening plans.

That the Fed risked over-tightening if it adhered to its original normalization plans is something Heritage’s Norbert Michel and I warned about, in an American Banker op-ed, a little over a year ago. “If the Fed keeps paying banks not to lend at the same time it starts slimming its balance sheet,” we said, “we could be in for very tight money.” That’s because the Fed’s plans called for it to shrink its balance sheet at a predetermined rate, while also adhering to a schedule of rate hikes aimed at re-establishing a supposedly “normal” effective funds rate sometime in 2019. Last May the Fed anticipated getting the funds rate back to 3 percent; since then it has lowered that goal to 2.8 percent.

That raising the IOER rate tightens money is obvious enough. But why, in a system in which banks hold trillions of dollars in excess reserves, should shrinking the Fed’s balance sheet itself lead to further tightening? The short answer is that, instead of being spread evenly throughout the banking system, excess reserves have mostly piled-up in a small number of very large banks, and especially in a handful of foreign banks with U.S. branches. For various reasons these banks find the return on reserve balances especially attractive compared to what they might earn by parting with those reserves. When the Fed was gobbling-up assets, these banks were gobbling-up reserves, thereby keeping them from contributing to any general increase in lending.

Now that the Fed has begun selling assets in order to buy-back reserves, the same IOER payments that encouraged certain banks to hoard reserves in the first place are discouraging them from parting with them. Instead, banks that held relatively small reserve cushions are choosing to swap reserves for other assets, and to rely more on federal funds to stay liquid. That means competing harder for a relatively small pool of fed funds, now supplied exclusively by GSEs, and driving the fed funds rate up closer to the IOER rate. (That the EFF rate never goes noticeably above the IOER rate is easily explained by the fact that the supply of fed funds becomes highly elastic at rates at or above the IOER rate, for such rates will convince even the most aggressive reserve hoarders to disgorge reserves.)

The question remains whether, and how, the new circumstances will alter the Fed’s future plans. Should money market conditions continue to tighten, Fed officials will face two options. One is to reduce their planned IOER rate increases, either by reducing their announced target range increases or by further increasing the difference between the IOER rate and the range’s upper limit. The other is to renege on their promised balance sheet unwind.

Not surprisingly, Fed officials appear increasingly inclined to take the latter course, and to thereby abandon a large chunk of their long-promised normalization plan. As the NYT reported,

That narrowing gap between the federal funds rate and the interest on excess reserves, or IOER, has stoked a debate over whether the Fed’s reduction of its massive bond holdings, which started in October 2017, has made it more expensive for banks to borrow excess reserves to meet regulatory requirements or fund their daily needs, analysts said.

This outcome was also one I predicted a while ago. In a March working paper version of Floored!, my forthcoming book-length critique of the Fed’s post-crisis operating system, I wrote that

the Fed’s determination to raise its policy rate (or rates) to a preconceived “normal” level, and to do so within a relatively rapid span of time, seems imprudent, and may, if pursued obstinately, ultimately cause it to further delay its planned balance sheet reduction, or even to abandon it altogether.

Of course, the Fed could easily stick to, or even hasten, its balance-sheet unwind, while still providing for a plentiful supply of federal funds, by lowering its IOER rate enough, relative to other market rates, to encourage the handful of banks now holding 90 percent of all excess reserves to part with them. But that would mean abandoning the Fed’s “floor” operating system, and establishing a “corridor” system in its place. Alas, whether its because they subscribe to some dubious Fed economics or for other reasons, most Fed officials seem unwilling to entertain such a switch — despite having once planned on it, and despite the well-established advantages of corridor systems, and their corresponding worldwide popularity.

It may yet be possible to change those officials’ minds. Let’s hope so. For if not, as I warned in a previous post, the day may not be far off when Mr. Powell finds himself transformed into the world’s first Six Trillion Dollar central banker. That is perhaps a burden he’s willing to bear. But it shouldn’t be one we’re willing to assign, to him or to any other mortal.