The pandemic has caused or accelerated the demise of numerous U.S. companies, and your local department stores are among the hardest hit. Government lockdowns and consumer reluctance in 2020 intensified longstanding pressures on the brick-and-mortar retail industry, pushing many iconic names, such as Neiman Marcus, J.C. Penney, and Belk, over the edge and into bankruptcy – events that have elicited laments about not only the companies and workers involved but the broader, long-term decline of brick-and-mortar retail and, by extension, the American middle class. Such claims, however, are heavy on nostalgia but light on facts – especially when it comes to the e‑commerce jobs replacing lost department store jobs. Indeed, while department store closures are undoubtedly difficult for the companies, workers, and (perhaps) communities involved, their secular decline has little to do with the state of the middle class and may, in fact, be something to celebrate.

On the first issue, the decline of department store jobs actually coincides with rising median personal incomes and disposable incomes (though the latter data are incomplete):

As we’ve discussed here previously, other data on middle-class wages and incomes show that the primary cause of the “shrinking” middle class is Americans moving up, not down, the financial ladder. Thus, there’s little data to suggest that “the collapse of America’s middle class crushed department stores.” Instead, this is far more likely a simple case of – pandemic aside – increasingly wealthy Americans preferring the convenience and variety of e‑commerce or the uniqueness of brick-and-mortar niche retail over the traditional department store model – a preference that anyone who’s recently wandered a cavernous department store looking for a shirt or toaster, only to find it’s out of stock, probably understands. (And don’t even get us started on the parking garages.)

Second, there’s reason for optimism when considering the jobs in e‑commerce that are most likely replacing many of those lost from department store closures. As Figure 2 below shows, e‑commerce and related jobs began their steady rise just as department store jobs began to fall (around 2010):

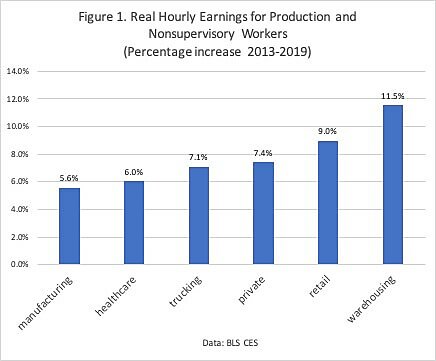

These e‑commerce jobs are not just increasing but – contrary to conventional wisdom – increasingly well-compensated. As the Progressive Policy Institute’s Michael Mandel recently explained, for example, the “e‐commerce era” (2013–19) has seen hourly earnings for production and nonsupervisory workers in the warehousing industry increase 11.5 percent (inflation-adjusted)—a much better pace than brick‐and‐mortar retail and other industries. In the last year, moreover, wage gains in retail/warehousing/delivery (5.2 percent) outpaced private-sector wage gains (4.4 percent).

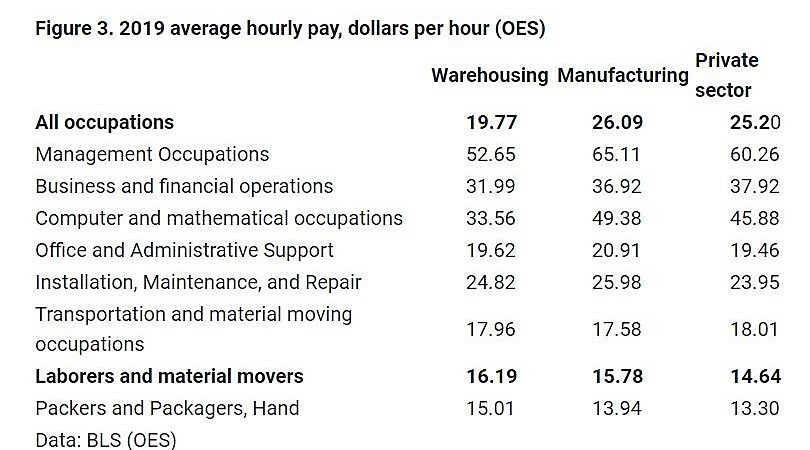

In fact, Mandel finds that “blue-collar” and administrative jobs in e‐commerce/warehousing now pay better than in the oft-revered manufacturing sector or the private sector overall, while the “picking and packing” jobs done by e‐commerce fulfillment workers “are clearly better paid than the typical jobs in the brick‐and‐mortar retail sector, by about 30 percent.”

With e‐commerce fulfillment centers popping up all over the country—there are 110 Amazon centers in the U.S. alone, and they’re planning 1,000 more (to compete with Walmart, which just announced raises for its e‑commerce workers)—these jobs are increasingly “local.” (Large e‑commerce sites often help small retailers (brick & mortar or otherwise) too – local jobs and output that wouldn’t be included in the data here.)

Furthermore, as Figure 3 below shows (latest data available), warehouse and other types of jobs in e‑commerce compare quite favorably to similar jobs at department stores:

As Mandel notes, the wage data above do not include benefits or alternative forms of non-cash compensation, for example, the company stock (“restrictive stock units”) that many Amazon employees receive. That many e‑commerce jobs do not require the standard workday schedule or can be done remotely also can provide workers with more flexibility and contribute to a better work-life-balance. (And as one of us who spent many long weekend hours on his feet in a Dallas Galleria shoe store can confidently state, those mall retail jobs are hardly cushy gigs.)

These figures also show the variety of jobs that e‑commerce companies – known for their sophisticated technology and unparalleled customer service – offer. Some require physical prowess and limited education or training, while others demand “soft skills” (for customer-facing operations), organizational skills (for managerial work), or even mathematics or engineering degrees.

All of this paints a much more hopeful message about the future of American retail and the dynamic U.S. labor market more broadly, as well as the necessity of considering the “creation” and not just the “destruction” in the standard Schumpeterian process. Retail – driven by both longstanding changes to consumer preferences and the more recent effects of COVID-19 – is undoubtedly experiencing disruptions that can be difficult for certain American workers. But many of the jobs lost are being replaced by jobs that are, on average, better than the old ones in several important ways (not to mention more responsive to consumer wants and needs). While this process can be painful for some, especially during a pandemic, it is an unavoidable part of economic growth – one that, contra the pessimism and nostalgia, will make us all better in the long run.