I must be losing my touch. I’ve let nearly two months pass without responding to Ezra Klein’s defense of RomneyCare, ObamaCare, and other centrally planned health care systems. (For those who want to get up to speed: his original post, my reply, and his response.) So here goes.

Klein notes that he and I had each used flawed measures of RomneyCare’s impact on health insurance premiums in Massachusetts. Fair enough. But Klein ignores the study I cited by John Cogan, Glenn Hubbard, and Dan Kessler, which estimates that RomneyCare increased premiums in Massachusetts by 6 percent. The CHK study has limitations, but it is the best estimate available. I hope Klein addresses it.

Klein’s fallback position is that even if RomneyCare increases premiums, that’s not an indictment of the law because cost-control was not one of its goals. Never mind that Mitt Romney boasted, “the costs of health care will be reduced.” Klein knows political rhetoric when he sees it. Yet he oddly sees no parallels between the phony-baloney promises of cost-control used to sell RomneyCare and the phony-baloney promises of cost-control used to sell ObamaCare — despite ample assistance from people like Medicare’s chief actuary and Alain Enthoven (“the American people are being deceived”).

Then Klein throws down his trump card:

[E]ven a cursory read of the evidence would show that whatever the drawbacks of central planning, it covers people at an extremely low cost. Romney Care’s cost problem is a result of pasting a coverage-oriented quick fix atop our insane health-care system. Compare its costs to the British system, the French system, the German system, or any other system, and whatever your conclusions, you won’t walk away unimpressed by the ability of centralized systems to cover whole populations for much less money than we spend.

Oy, where to begin? First, Klein violates Cannon’s First Rule of Economic Literacy: he writes that centrally planned systems cost less, when what he means is that they spend less.

Second, the phrase “whatever the drawbacks of central planning” is some serious hand-waving. Those “drawbacks” include (among other things): the Medicare program’s suppression of comparative-effectiveness research, error-reduction efforts, care coordination, and other delivery innovations; Canada’s human-rights violating Medicare system; and the suppression of untold innovations in health insurance and medical treatment by government price controls. Other than a few drawbacks, Mrs. Lincoln…

Third, our “insane health-care system,” as I blogged previously, “is the product of the old raft of government price & exchange controls, mandates, and subsidies.” Prior to ObamaCare, government already controlled half of all U.S. health care spending directly, granted control over another quarter to employers, and regulated health care more heavily than perhaps any other sector of the economy. Klein and his fellow central planners can’t deny paternity. Our “insane health-care system” is the product of central planning.

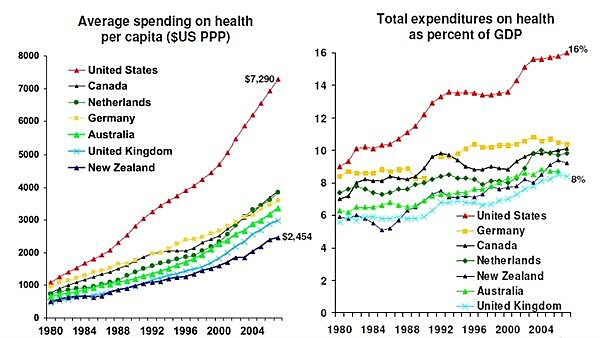

Finally, only a cursory read of the evidence could lead to the conclusion that central planning contains health care spending. Klein posts the following charts and concludes that since all those (other) centrally planned systems spend less on health care than the United States, central planning must result in lower health care spending.

Photo credit: By Robert Giroux/Getty Images[/caption]

But if that were true, then one would expect per-capita spending on elderly Americans — who have universal coverage through the centrally planned Medicare program — would not be far out of line when compared to how much other nations spend per elderly resident. Yet the United States is just as far out of here as overall. According to the OECD, the United States spends about twice as much per elderly person as Canada, and more than twice as much as Australia spends. (Alas, I’m not cherry-picking; these are the only four nations for which the OECD provides recent data.)

[caption align=“aligncenter”]Source: OECD, author’s calculations[/caption]

(One could argue that the reason for this is that Medicare exists alongside the world’s largest (ostensibly) private health care sector, whose evils spill over into Medicare. If that were the case, then moving all Americans into Medicare should reduce U.S. health care spending, bringing it back into line with other nations. But consider that Klein and The New Republic’s Jonathan Chait both acknowledge that Congress had to throw $2 at the health care industry for every $1 that ObamaCare cut from future Medicare spending. How exactly could Congress move 250 million Americans into Medicare (which presumably would reduce overall spending), or reduce Medicare spending later, given those constraints? How, exactly, would an independent rationing board survive the political dynamics that produce such outcomes? Prediction: it won’t. The narrative that central planning contains health care spending just doesn’t hold water.)

Klein, The New Republic’s Jonathan Cohn, and others have taken a big step by acknowledging that RomneyCare is struggling. When they shift the blame to “the American health care system,” however, they obscure what’s really happening. As I closed my previous post: “RomneyCare and its progeny ObamaCare are attempts by the Left’s central planners to clean up their own mess. If Klein and Cohn want to defend those laws, pointing to the damage already caused by their economic policies won’t do the trick. They need to explain why government price & exchange controls, mandates, and subsidies will produce something other than what they have always produced.”