T

he shadow banking literature has vastly and rapidly expanded since the financial crisis, and has produced some interesting pieces, as well as some exaggerated claims, in my view. While I am not writing today to address those claims, I still wish to question a closely linked concept that has simultaneously sprung up in the literature and in particular in the post-Keynesian one: shadow money.One of the most elaborated and comprehensive academic research papers on this particular topic is the recently published Gabor’s and Vestergaard’s “Towards a theory of shadow money.” It’s an interesting and recommended piece. But while I agree with some of their writings, I have to find myself in disagreement with a number of their points and examples* and in particular their central claim: that repurchase agreements (“repos” thereafter) are shadow money; that is, a type of monetary instrument used within the shadow banking system.

For some readers that might not know how a repo works, below is a concise definition provided by the IMF:

Repo agreements are contracts in which one party agrees to sell securities to another party and buy them back at a specified date and repurchase price. The transaction is effectively a collateralized loan with the difference between the repurchase and sale price representing interest. The borrower typically posts excess collateral (the “haircut”). Dealers use repos to borrow from MMFs and other cash lenders to finance their own securities holdings and to make loans to hedge funds and other clients seeking to leverage their investments. Lenders typically rehypothecate repo collateral, that is, they reuse it in other repo transactions with cash borrowers.

Given repos’ (and their asset counterpart: reverse repos) properties, my view is that repos aren’t shadow money but a shadow funding instrument. While it might not sound such a big issue, I believe the distinction is important from an analytical perspective as well as to avoid confusion. Let me elaborate.

Gabor and Vestergaard define shadow money as “repo liabilities, promises backed by tradable collateral.” According to them, shadow money has four key characteristics:

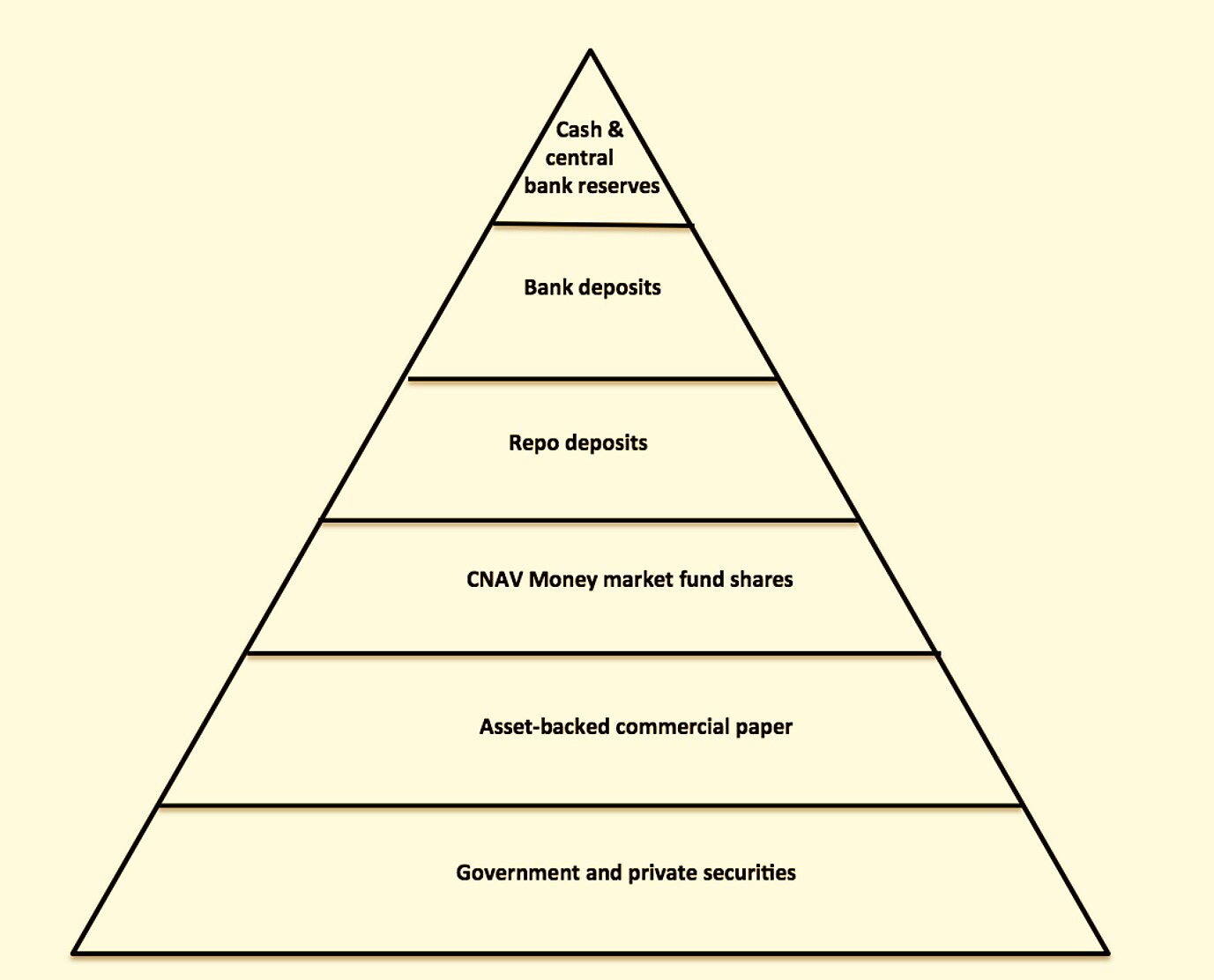

a) In modern money hierarchies, repo claims are nearest to settlement money, stronger in their “moneyness” than ABCPs or MMF shares.

b) Banks issue shadow money. The incentives to issue repos are incentives to economize on bank deposits and bank reserves.

c) Shadow money, like bank money, relies on sovereign structures of authority and creditworthiness. The state offers a tradable claim that constitutes the base asset supporting the issuance of shadow claims.

d) Repos create (and destroy) liquidity at lower levels in the hierarchy of credit claims.

They offer this chart of “modern” money hierarchy:

I have to object to repos being classified as “money.”

Money, as typically defined by economists, has three characteristics: it is a medium of exchange, a unit of account and a store of value. High-powered money (the “outside money” of the financial system) currently fits this definition, as a final settlement medium.

The “moneyness” concept, a term now popularised by JP Koning’s excellent blog, asserts that various types of assets have various degrees of money-like properties. In this quite old but classic post, JP argues that anything from beers and cattle to deposits benefits from some degree of moneyness. In another old post, Cullen Roche provided the following good “money spectrum” chart (although I’d disagree with his outside money/deposit ranking):

Therefore, most goods and assets have some monetary properties: some can be used as media of exchange or store of value. All represent a claim of some sort on money proper. As a general (but inaccurate) rule, the more their price in terms of outside money fluctuate, and hence their conversion risk raises, the further away they are on the moneyness scale. But conversion (almost) on demand also implies that, in order to have some money characteristics, a good or asset needs to be tradable.

Now let’s get back to repos as shadow money.

Repos are a liability issued by the debtor in exchange for high-powered money, of which reverse repos are the asset counterpart held by the creditor (and hence the claim on the high-powered money originally transferred, plus interest). The debtor also transfers an extra asset (i.e. the collateral) to the creditor for security purposes at a pre-agreed haircut depending on its credit quality and market risk sensitivity.

We get here to the main point of this post: repos have little money-like property due to their non-tradability and lack of on-demand convertibility.

Indeed, a repo liability is of course non-tradable, in the same way that any debt that one owes cannot be traded for another type of liability. It can only be refinanced and/or extinguished. A reverse repo (or repo claim) however, could potentially have tradable properties, allowing a creditor to exchange his claim almost instantaneously on the market. Problem is: this does not happen. Unlike bonds or other assets, and due to the very specific features of such private agreements, there is no secondary market for repo claims. Once a repo has been agreed upon, the contract is fixed between the two parties until maturity (or default). Consequently, repo claims can effectively be assumed to have no liquidity.

Seen this way, it is hard to classify repos as “money,” and they certainly do not deserve their third place in the moneyness hierarchy above. So what are repos? As I previously said, they are a funding instrument. Given that the shadow banking system makes use of repos on a large scale, we can potentially call them a “short-term secured shadow funding instrument.” And please note that repo issuance isn’t limited to banks and broker-dealers; other institutions also use them.

You’ll be tempted to reply: “what about deposits? They have no secondary market and are not tradable either.” This isn’t strictly accurate. While they are both promises to pay a certain amount of money proper at a certain date, there is a very specific difference between deposit liabilities (“on demand” ones especially) and repo liabilities. Banks themselves are deposits’ secondary market: deposits can be ‘traded’ within the bank’s own balance sheet and swapped for cash on demand. And when dealing with a counterparty that does not hold an account with the same bank, banks take over the responsibility of transferring the underlying funds (i.e. high-powered money).

If repos aren’t “money”, what else could be considered “shadow money?” Well, assets provided as collateral do have liquidity, tradability, and therefore some “moneyness.” Those assets can sometimes be used in further transactions. This is why I am wondering whether or not there isn’t some confusion with “shadow money” proponents’ terminology. While their writings clearly emphasise the “shadow money” nature of repos themselves (and Poszar seems to be using the same definition here), many other academic authors have instead referred to the most commonly-used types of repo collateral (high quality and highly liquid sovereign and corporate bonds) as “shadow money” (which indeed makes more sense to me, although I do not fully adhere to this concept either).

There are plenty of things worth discussing regarding this theory of shadow money and the use of repos in general, but the money-like properties of repurchase agreements isn’t one of them. Let’s focus on their funding properties instead.

______________

*I also believe that their shadow money expansion theory is subject to the same critique as other endogenous outside money theories, such as MMT’s.

PS: The fact that repos are backed by marketable collateral does not confer any specific monetary property to repo claims. Marketable collateral is used in many other types of lending transactions, in particular in private banking-type lending. Also, repos and any other collateralised lending are expected to be repaid at par, independently of the valuation fluctuations of their underlying collateral.

PPS: Baker and Murphy build on Gabor’s and Vestergaard’s piece and just published a blog post that argues for a new “investment state,” in a typical post-Keynesian interventionist fashion.

[This article originally appeared on Spontaneous Finance]

Disclaimer

This post was originally published at Alt‑M.org. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Cato Institute. Any views or opinions are not intended to malign, defame, or insult any group, club, organization, company, or individual.

All content provided on this blog is for informational purposes only. The Cato Institute makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information on this site or found by following any link on this site. Cato Institute, as a publisher of this article, shall not be liable for any misrepresentations, errors or omissions in this content nor for the unavailability of this information. By reading this article and/or using the content, you agree that Cato Institute shall not be liable for any losses, injuries, or damages from the display or use of this content.