News this week that Ford Motor Company will invest $1.6 billion to build a new small-car production plant in Mexico has elicited the usual responses from the usual politicians, each one decrying “un-American” companies and a U.S. trade policy that encourages multinational corporations (MNCs) to invest in countries with cheap labor or other “unfair” advantages over the United States. Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump, for example, called Ford’s decision an “absolute disgrace” that – similar to recent offshoring decisions by Carrier and Nabisco before it – shows just how badly America is “losing at trade” and just how horribly our free trade agreements have hurt the American working class.

Trump’s critique, echoed by other protectionist candidates and the news outlets that love them, is nothing new: it’s basically the same dire warning of a “giant sucking sound” of investment moving offshore that candidates like Pat Buchannan, Ross Perot and John Edwards have been spewing ever since the United States first started liberalizing trade through the NAFTA. Yet, like most things Trump and trade, the candidate is very wrong, having erroneously treated a few highly-publicized and emotional anecdotes as if they are broadly representative of American economic reality.

Indeed, a quick look at the latest facts on U.S. and global investment show that not only is there no “giant sucking sound” here, but America remains, by far, the world’s top investment destination.

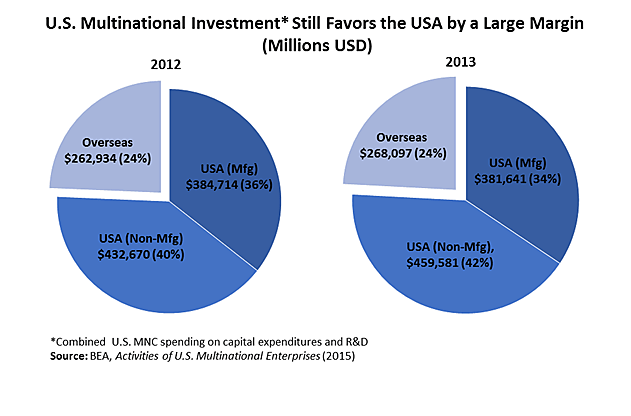

First, American MNCs continue to invest far more in their domestic operations than in their offshore affiliates. In fact, the most recent Bureau of Economic Analysis report on the Activities of U.S. Multinational Enterprises finds that these firms spent about three times as much on capital expenditures and research & development at home as they did abroad in 2012 and 2013 (the latest data available). In fact, U.S. manufacturing MNCs alone invested about one-and-a-half times as much in the United States in 2012 and 2013 as all U.S. MNCs invested abroad during the same years:

The numbers for automakers like Ford aren’t this stark, but they’re still impressive: the Center for Automotive Research estimates that, of the $18.25 billion in additional North American investments that U.S. car companies announced in 2014, $10.5 billion was earmarked for projects in the United States, while $7 billion and $750 million was planned for Mexico and Canada, respectively. These numbers demonstrate that, while Ford and other MNCs might occasionally choose to invest in Mexico or elsewhere, they’re still investing heavily in the United States too.

Furthermore, more investment by American MNCs abroad does not mean less investment at home. Additional crunching of the same BEA dataset by my colleague Dan Ikenson reveals that MNCs’ investments in their U.S. and foreign operations are complementary, not substitutes. In other words, one more dollar spent by U.S. multinationals abroad does not translate to one less dollar spent in the United States; in fact, it’s much the opposite: expansion abroad typically means expansion here at home too. These data destroy the myth, advanced by Trump and others, that when Ford and others choose to send their investment dollars abroad, American jobs go with them.

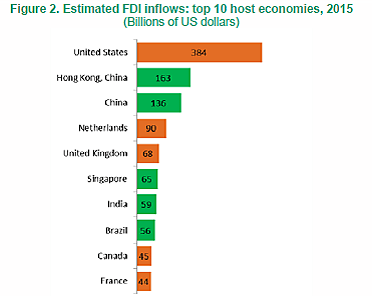

Second, there is little evidence that the United States is “losing” at the global investment game: America remains the world’s top destination for foreign direct investment (FDI), and it’s not even close. The UN Conference on Trade and Development estimates that FDI inflows into the United States in 2015 reached their “highest level since 2000” at $384 billion – more than double second place Hong Kong and almost triple third place China:

This pole position is not unusual – except for a one-time blip in 2014 due to a major telecommunications merger, the United States routinely sits atop UNCTAD’s FDI rankings. Such position makes clear that, despite America’s policy faults, the country remains the most attractive investment destination in the world.

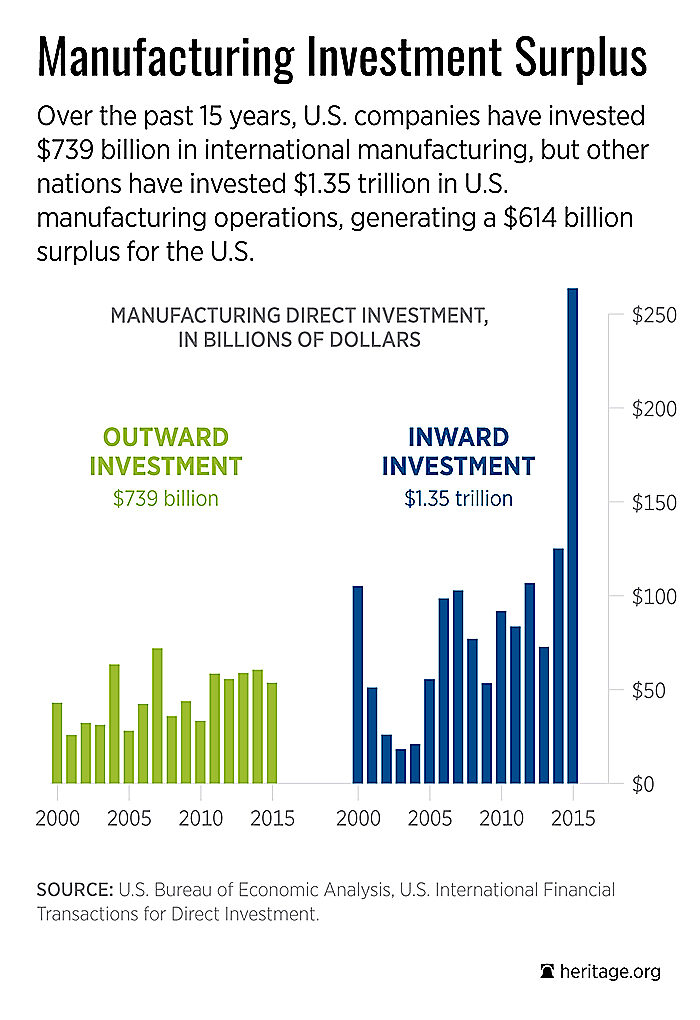

And this foreign investment isn’t just going to sexy, innovative sectors like information technology; it’s going to American manufacturing too. According to new research from the Heritage Foundation’s Bryan Riley, the United States amassed a whopping $614 billion “manufacturing investment surplus” with the rest of the world between 2000 and 2015:

Riley’s data, also from the BEA, further demonstrate the eye-popping magnitude of the United States’ comparative advantage as a global investment destination – one that should finally put to rest the silly notion that U.S. and global trade and investment liberalization has caused American manufacturers and services providers to leave our shores for greener, cheaper pastures (or for foreign companies never to arrive). Sometimes U.S. (or foreign) companies invest abroad; more often they invest here. That decision is based on a complex, company-specific examination of cost and other factors, not some rudimentary quest for the cheapest labor or slackest environmental regulations.

There are certainly things that the U.S. government could do to improve the country’s attractiveness as a global investment destination – reforming one of the world’s most onerous corporate tax regimes is an obvious place to start, as is fixing our increasingly-sclerotic labor market. But the numbers here leave little doubt that, for now at least, the only “giant sucking sound” we’re hearing in America is the one of investment dollars being hoovered into the U.S. economy, not out.

The views expressed herein are Mr. Lincicome’s alone and do not necessarily reflect those of his employers.