Republican Senators Tom Cotton (AR) and David Perdue (GA) are unveiling a bill today at the White House that would slash the number of legal immigrants by about 50 percent over the next decade. This bill will be very similar to the RAISE Act that both Senators introduced in February, which I criticized here. Their new bill, if it is similar to RAISE, would cut legal immigration by about 50 percent by reducing family reunification, eliminating the diversity visa, and statutorily limiting refugees without increasing skilled-worker immigration. So much for the talking point that immigration hawks are “only against illegal immigration.”

Cotton-Perdue Does NOT Create a Skills-Based Immigration System

Supporters are saying that this bill would create a “skills-based immigration” policy but nothing could be further from the truth. Cotton-Perdue does not increase skilled immigration at all – it only cuts non-employment categories like families and the diversity visa while creating a points-based system for employment-based green cards that does not increase the numerical cap. The new Cotton-Perdue bill would do nothing to boost skilled immigration and it will only increase the proportion of employment-based green cards by cutting other green cards. Saying otherwise is grossly deceptive marketing.

President Trump stated that he wanted to create a merit or skills-based immigration system like in Canada or Australia, but the Cotton-Perdue bill would not come close to achieving that goal. The immigration systems in Canada and Australia do emphasize skilled immigrants over family members but their immigration systems allow in far more immigrants, as a percentage of the population in both countries, than the United States. It is important to control for the population of the destination country when comparing the relative openness of different immigration systems.

New immigrants to Canada who arrived in 2013 were equal to 0.74 percent of that country’s population. New immigrants to Australia in 2013 were equal to a whopping 1.1 percent of their population. By contrast, immigrants to the United States in the same year equaled just 0.31 percent of our population. The only OECD countries that allow in fewer immigrants relative to their populations than the United States are Portugal, Korea, Mexico, and Japan. Seventeen other OECD countries allow in more immigrants than the United States as a percentage of their populations.

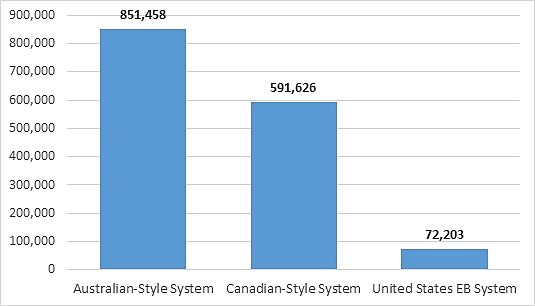

In 2013, the number of skilled-worker immigrants to Canada was equal to 0.18 percent of that country’s population. If the Cotton-Perdue bill intended to copy Canada’s skills-based immigration system, then it would increase the number of annual employment-based green cards from the current level of about 75,000 to about 592,000 annually – a 7.9-fold increase in the number (Figure 1). If the Cotton-Perdue bill wanted to copy Australia’s skills-based immigration system then it would have to increase employment-based immigration to about 852,000 annually – an 11.4-fold increase.

Figure 1

Annual U.S. Employment-Based Immigrants under Different Immigration Regimes, 2013

Sources: OECD, EuroStat, E‑Stat, Citizenship and Immigration Canada, Department of Homeland Security, Author’s Calculations.

Because Canada and Australia allow in more skilled immigrants, the number of family-based immigrants admitted as a proportion of their respective populations is also higher relative to the United States. In 2013, family-based immigrants to Australia and Canada were equal to 0.26 percent and 0.23 percent of their respective populations. Family-based immigrants to the United States in 2013 were equal to just 0.21 percent of our population in that year. An important caveat is that Canada and Australia do not allow in as many distant relatives as the United States. If Canada and Australia are the models for a skills-based immigration system, as President Trump stated, then the result would be more family-based immigrants in addition to more skilled-immigrants.

Canada and Australia also have large-scale regional immigration systems that allow Provinces and States, respectively, to allow in foreign workers in addition to their federal systems. Senator Johnson (R‑WI) introduced a bill this year to create just such a state-sponsored migration system in the United States that is modeled on the Canadian program and would accrue tremendous benefits to Americans. Senator McCain (R‑AZ) recently became a co-sponsor. Any bill that would seek to create a skills-based immigration system based on the Australian or Canadian models would include a state-sponsored migration system like the type proposed by Senator Johnson.

Cotton-Perdue Will Not Raise Wages

The RAISE Act was named after its intent to raise the wages of native-born American workers by reducing the supply of lower-skilled immigrants. However, that has not been the effect of immigration restriction in American history. Congress restricted immigration to raise American wages at least three times in American history – 1882, 1924, and 1964. It failed each time.

Congress’ 1964 cancellation of the Bracero program is most instructive. Bracero was a guest worker visa that allowed Mexican workers to migrate to American farms. Congress canceled it after intensive lobbying by labor unions and bad publicity due to flaws in the program. Economists Michael Clemens, Ethan Lewis, and Hannah Postel took advantage of this natural experiment that was “designed to raise domestic wages and employment by reducing the total size of the workforce” to see how American farm wages adjusted. Their superb paper found that canceling Bracero had little measurable effect on wages.

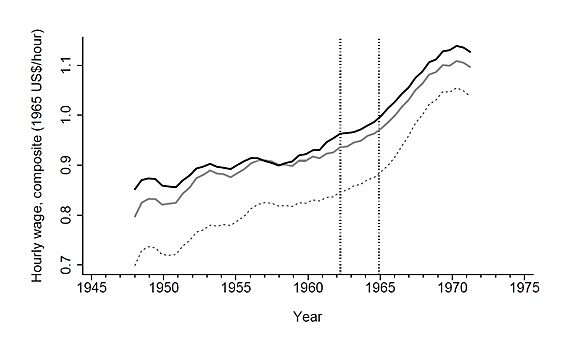

Figure 2

Farm Worker Wages before and after Bracero, by State

Figure 2 from their paper compares the quarterly average real farm wages by states where Braceros made up more than 20 percent of seasonal agricultural labor (black line), states where Braceros were fewer than 20 percent of the workforce (gray line), and states where there were no Braceros at all or only negligible numbers (dashed line). Clemens et al. write that “[t]he figure shows that pre- and post-exclusion trends in real farm wages are similar in high exposure states and low-exposure states. It also shows that wages in both of those groups rose more slowly after bracero exclusion than wages in states with no exposure to exclusion.” The farmers did not adapt to the decline in legal migrants by raising wages. Instead, they mechanized and planted less labor-intensive crops.

The similarities between Bracero’s cancellation and the Cotton-Perdue bill are enough to make this new research a compelling reason to reject the bill out of hand. The first similarity is that the Bracero program allowed in half a million workers a year before it was eliminated – which is about the same number of green cards that the Cotton-Perdue bill would cut. Second, Bracero workers are somewhat similar to the workers who would enter on the family-based green cards that Cotton-Perdue intends to cut. Third, Braceros were also concentrated in some states just like new immigrants are. The historical and economic experience with cutting legal immigration in the past should deter would-be supporters of this bill.

Furthermore, immigration bears little blame for low wages. The National Academy of Sciences’ (NAS) literature survey on the economic effects of immigration concluded that:

When measured over a period of 10 years or more, the impact of immigration on the wages of native-born workers overall is very small. To the extent that negative impacts occur, they are most likely to be found for prior immigrants or native-born workers who have not completed high school—who are often the closest substitutes for immigrant workers with low skills.

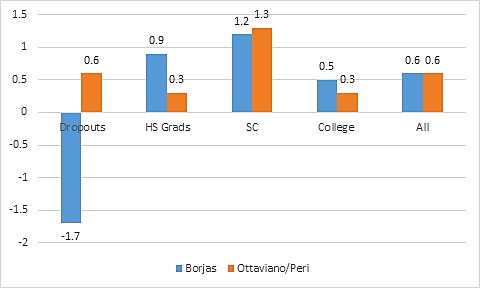

Furthermore, the small long-run relative wage impacts on native-born American workers by education are close to zero according to the most authoritative studies by economists George Borjas and Gianmarco Ottaviano and Giovanni Peri, both of which take up much of the NAS report. They disagree when it comes to immigration’s impact on the wages of dropouts, even though the effect is small and positive for all native-born workers lumped together in both studies (Figure 3). The 2015 American Community Survey reports that only 9.4 percent of native-born Americans over the age of 25 are dropouts – the category of native-born workers who are most likely to be negatively affected. Thus, over 90 percent of American workers are in education-skill categories where immigrants increase relative wages according to George Borjas’ relatively negative findings.

Figure 3

Relative Impact of Immigration on Native Wages by Education

Sources: Borjas, p. 120; Ottaviano & Peri, Table 6.

Note: Borjas looks at 1990–2010. Ottaviano and Peri look at 1990–2006.

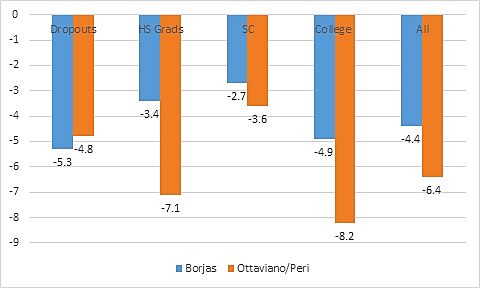

Assuming that the Bracero research by Michael Clemens, Ethan Lewis, and Hannah Postel does not apply to Cotton-Perdue, which is extremely unlikely, the main potential beneficiaries are other immigrants. Both Borjas and Ottaviano & Peri find that the wages of immigrant workers do drop because of competition with new immigrants even though native wages do not (Figure 4). That is because new immigrants have skills and educations most similar to previous immigrants, so they compete against each other more than with natives who have different skill and education levels. Reducing immigrant wage competition with immigrants is not a popular goal for the population most affected. Figure 25 of this Bulletin shows that immigrants are much more likely to support liberalized immigration in spite of wage competition.

Figure 4

Relative Impact of Immigration on Immigrant Wages by Education

Sources: Borjas, p. 120; Ottaviano & Peri, Table 6.

Note: Borjas looks at 1990–2010. Ottaviano and Peri look at 1990–2006.

Cotton-Perdue Is a Bad Political Bargaining Chip

More seasoned political observers around Washington DC suspect that the Cotton-Perdue bill is intended to be a bargaining chip that they can drop in exchange for other reforms like mandated E‑Verify or another large-scale increase in immigration enforcement. This is similar to when proponents of the 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) originally included cuts to legal immigration but had to settle for only boosting enforcement when many Republicans supported preserving the legal immigration system.

Cotton-Perdue is not a good political bargaining chip for at least two reasons. First, virtually zero Democrats would support a cut to green cards and at least half of Republicans would join them. Cotton-Perdue will die on its own due to lack of support – like the RAISE Act did a few months ago – or be stripped out of any immigration bill in which it was included. The bill has no chance so it cannot be credibly used as a bargaining chip to gain concessions elsewhere despite what President Trump says today. Second, the public is more supportive of immigration than it was in the mid-1990s when Congress last seriously considered cuts in the legal system. In 1995, 65 percent of Americans wanted less immigration while only 38 percent do today. Cotton-Perdue would not be popular on Capitol Hill or with the American electorate so it is not a credible bargaining chip.

Conclusion

The Cotton-Perdue bill would not create a skills-based immigration system as President Trump has said he wants, it will not increase American wages, and it is not a credible bargaining chip in any future negotiations in Congress. Interestingly, the current U.S. immigration system is gradually selecting a higher proportion of skilled immigrants over time without Congressional reform. The Cotton-Perdue bill deserves to be criticized but it is not a serious threat that should gain concessions from Congressmen or Senators in both parties who either support immigration reform or the current level of admissions.