The House Homeland Security Committee will markup and likely pass the Border Security for America Act (H.R. 3548) today. Among the bill’s 95 pages is this:

The Secretary of Homeland Security shall take such actions as may be necessary (including the removal of obstacles to detection of illegal entrants) to construct, install, deploy, operate, and maintain tactical infrastructure and technology in the vicinity of the United States border to deter, impede, and detect illegal activity in high traffic areas.

Media outlets are describing this as codifying Trump’s “border wall.” I have previously detailed the numerous problems with building a border wall, including the fact that it would require huge amounts of private land along the Southern border. This deprivation of the right to private property is serious, but it’s compounded by the fact that the government seizes the land first and only then, many years later in some cases, provides just compensation. Unfortunately, the Supreme Court has long ago signed off on this procedure. It’s a problem that Congress must fix.

The Problem of Seizing Private Land

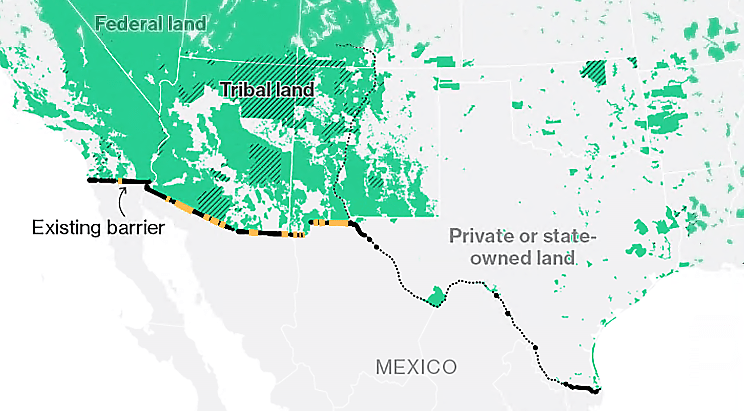

Figure 1 is a map of the border that shows the federally owned portions in green. Tribal land, which comes with its own restrictions, is green with black stripes. The existing border fencing is in black and yellow. The yellow portions are vehicular barriers, and the bolded black is the pedestrian or “real” fence. The dotted line in Texas is the Rio Grande River. As you can see, most of Texas is without any barriers and is almost entirely privately owned.

Figure 1

Border Fencing and Federal Land

Source: Bloomberg

One reason why Congress built the fences where it did is due to the problems associated with seizing private land. In July 2007, Customs and Border Protection spokesperson Michael Friel explained to The Seattle Times that the fences “were going up first in New Mexico, Arizona and California, where much of the land already belongs to the federal government.” He added, “We realize that in Texas there are folks that own property, that have land on the border. That dynamic is different.”

DHS’s Inspector General (IG) concluded in 2009 that “acquiring non-federal property has delayed the completion of fence construction,” and that “CBP achieved [its] progress primarily in areas where environmental and real estate issues did not cause significant delay.” The IG report again:

For example one landowner in New Mexico refused to allow CBP to acquire his land for the fence. The land ownership predated the Roosevelt easement that provides the federal government with a 60-foot border right-of-way. As a result, construction of fencing was delayed and a 1.2‑mile gap in the fence existed for a time in this area. CBP later acquired this land through a negotiated settlement.

The IG found more than 480 cases in which the federal government negotiated the “voluntary” sale of property, and up to 300 cases in which condemnation would be sought through the courts.

Legal Process and Legal Authority to Seize Private Land

Congress has already given the administration authority under a 1996 law and a 2006 law to condemn and seize land using eminent domain to build barriers. One way to address eminent domain along the border is simply to ban it. Rep. Ruben Gallego (D‑AZ) has introduced a bill today that would do so. This would be effective, but it may not be politically feasible, given the wall fever that has descended on Congress.

Another approach would address the process. Right now, when Border Patrol wants to take someone’s land, they send them a letter offering them a nominal low sum of money for their land and threatening to file condemnation proceedings against them if they don’t accept it. In 2006, when the Secure Fence Act fences were built, many property owners accepted the low offer because they did not understand their right to negotiate over just compensation in court. Just compensation is a constitutional guarantee. Under the 5th amendment, “private property [cannot] be taken for public use, without just compensation.”

Just compensation refers to the fair market value of the property seized—what you could get for the land if you attempted to sell it—but less than what you would demand to receive in a voluntary sale. But in many cases, the seizure of a single strip of property in the middle of someone’s property can depreciate the value of the entire land. For this reason, it is necessary to present evidence in a court of the total impact of the seizure to the landowner. Other issues that may arise in this process are the exact boundaries of someone’s property and who exactly holds financial interests in the land. These issues also take time to sort out.

Seizures without Just Compensation

Here’s the problem: under the eminent domain statute, the federal government can seize property almost as soon as they file a condemnation proceeding—as soon as the legal authority for the taking is established—then they can haggle over just compensation later. It’s called “quick take.” Quick take eminent domain creates multiple perverse incentives for the government. 1) They can quickly take land, even when they don’t really need it, and 2) they have no real incentive to compromise or work with the land owner on compensation. The land owner’s bargaining power is significantly diminished. The federal government already possesses the property.

This means that for years, people who are subject to a border wall taking go without just compensation. The government is supposed to compensate the landowner for this time by paying interest on the agreed amount. But in the real world, many people cannot survive for years being deprived of income that they might have from the land. According to an NPR analysis of 300 fence cases, the resolved cases took more than three years to resolve. In other cases, the process took seven, eight, or even 10 years. Some cases are still pending a decade on.

Congress could rectify this injustice by requiring the federal government to work out just compensation before the wall is built or, better yet, before the land is taken. That would give the landowner a fair position to negotiate with the government and give the government a reason to respect their rights. That it would slow up a pointless waste of taxpayer dollars is just an added bonus.