Something promising is happening at the Department of Housing and Urban Development. Recent New York Times and Wall Street Journal articles suggest Secretary Ben Carson and his team are impressing on policymaker’s minds that 1) local policymakers have created housing affordability problems and 2) local policymakers can solve those problems.

According to the Times article, “as city and state officials and members of both parties clamor for the federal government to help, Mr. Carson has privately told aides that he views the shortage of affordable housing as regrettable, but as essentially a local problem.”

Meanwhile, a Journal article published this week reports “[Carson] plans instead to focus on restrictive zoning codes. Stringent codes have limited home construction, thus driving up prices and making it more difficult for low-income families to afford homes, Mr. Carson said.”

Carson is right to describe housing affordability as a local problem, and smart to signal HUD can’t and won’t solve the problem for local policymakers.

For its part, Cato scholars have argued for zoning reform in numerous places. Earlier this month, Cato Institute published a new issue brief on zoning regulation and housing prices. Elsewhere I’ve written about zoning in the context of Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing, the controversial HUD rule the agency opened for public comment and revision earlier this week.

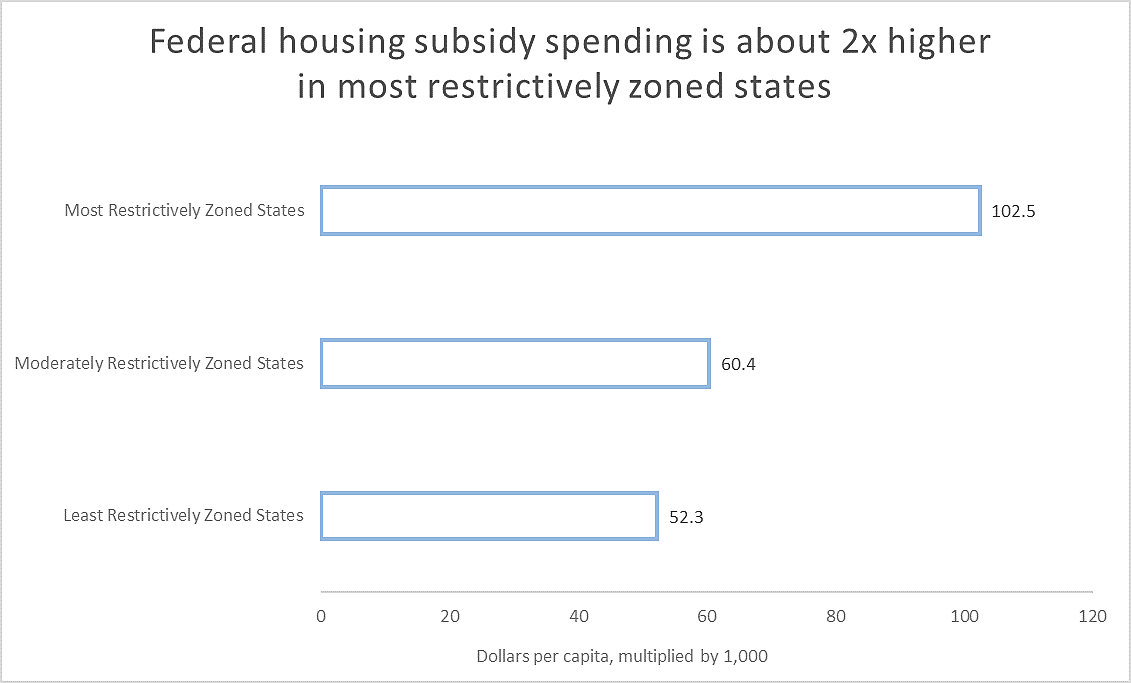

Carson seems to understand that federal assistance has encouraged poor local policies. In a Cato report published last year I show that the federal government subsidizes housing in states with more restrictive zoning at higher rates than those with less restrictive zoning. Specifically, the most-restrictively zoned states receive nearly twice the federal dollars per capita compared to the least-restrictively zoned states (see figure).

Because restrictive zoning drives the cost of housing up, local governments actively undermine the purpose of federal housing subsidies when they adopt restrictive zoning and land use policies. HUD staff have mentioned housing vouchers cost more money each year to service the same number of people.

Local zoning regulations grow every year, so it makes sense HUD would see climbing costs. For fiscal conservatives that care about efficiently using government dollars, attaching pro-market zoning requirements to HUD grants is arguably a cost-saving device. Pro-market zoning requirements also support the purpose of housing affordability subisidies by ensuring cities are doing their part to allow development.

Determining whether attaching requirements to grants is a constitutionally-sound strategy is best decided by a legal expert. However, Carson’s new focus on educating policy makers on the damaging consequences of local policy, while acknowledging HUD cannot overcome local problems by spending money, is a welcome change.