In my opening post about Scottish banks’ suspension of specie payments, I explained that, although the suspension was technically illegal, it failed to provoke any lawsuits in part because it was no less in the interest of many Scottish citizens, and Scottish bank creditors especially, than it was in that of Scottish bankers themselves. Rather than sue their banks, large numbers of prominent Scotsmen resolved publicly to make and receive payments in notes issued either by the Bank of England or by the Scottish banks themselves.

But while many Scots may have been willing, at least grudgingly, to accept bank notes rather than specie in payments, it doesn’t follow that none were harmed by the suspension. In today’s post I’ll consider just what the costs were, and who bore them. I’ll then turn in my third and final post to considering whether these costs should be regarded as a black mark against the Scottish bankers, and as a reason for denying that the Scottish free banking episode serves as a good example of the advantages of unregulated banking.

Gold versus Paper

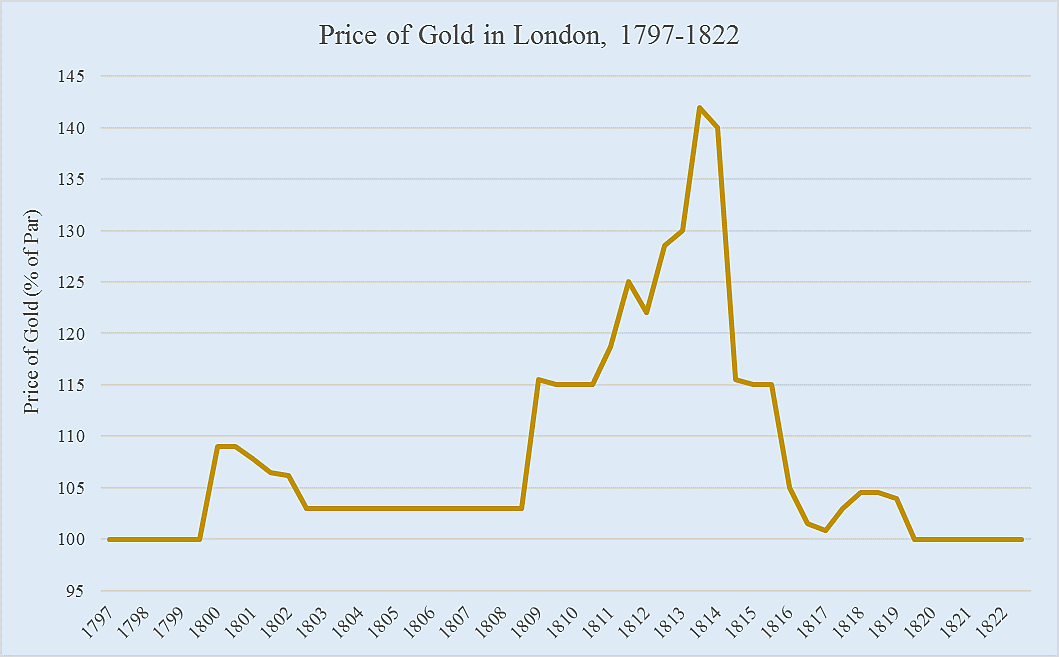

The most obvious way in which holders of Scottish banknotes may have suffered from the suspension of specie payments would have been by finding that those notes were no longer worth their par value in gold, that is, that the cost, in banknotes and subsidiary coin, of an ounce of fine gold had risen above £3 17s 10.5d.[1]

It is, moreover, tempting to assume that the suspension led to an immediate and substantial decline in banknotes’ value, by eliminating what had been a crucial check against banks’ temptation to over-issue paper currency, thereby undermining the public’s confidence in it.

In the present instance, however, that’s not what happened. Instead the public, reassured by the British government’s promise that the Bank Restriction was to be a temporary measure only (and despite repeated extensions of the deadline for resumption), retained its confidence in paper currency to a remarkable degree. For its part the Bank of England continued to regulate its note issues as if specie payments hadn’t been suspended at all, no doubt in part because its directors also understood that they might be obliged to resume payments within a relatively short time. Scottish and English country banks in turn continued to be no less disciplined by the scarcity of Bank of England paper than they had formerly been by the scarcity of specie.

The upshot of all this, as can be seen in the chart below, is that a substantial portion of the Bank Restriction era banknotes, and Bank of England notes in particular, did not suffer any substantial loss of value relative to gold. Until 1808 the premium approached 10 percent on one occasion only — during the first quarter of 1801. Generally it was insignificant. (Even during the long stretch, between 1803 and late 1808, when the chart shows a constant 3 percent premium, gold’s market price was often lower, the 3 percent premium having been one that the Bank of England alone elected to pay at the time as a matter of its own peculiar policy.) “Month after month had passed away,” Henry Adams observes,

not only without bringing depreciation, but even rapidly increasing the stream of precious metals which flowed toward England, so that people were little inclined to dwell upon the dangers or temptations of restriction, and probably overestimated its value as a safeguard against panic.[2]

Following the 1801 spike, gold again fell close to par, from which it varied only insignificantly until 1808, thanks in part to the British governments’ willingness to limit its demands upon the Bank for wartime accommodation.

For some purposes, of course, and especially for that of paying for foreign goods, banknotes were no substitute for gold. But in that case, provided the particular need for gold could be demonstrated, the Scottish banks were often prepared to accommodate it, albeit quietly. “There is reason,” says William Graham,

to believe that cash [specie] payments were not stopped so entirely in Scotland as they were at the Bank of England. All the Scots banks kept stocks of gold, and it is probable that, notwithstanding the theory that the notes of Scotland turned out the gold, there was more gold in the country than was generally supposed, for the more prudent measures of the banks in their exchanges and issues could not fail to attract some of the gold which was displaced by excessive issues in England.[3]

In any case, gold could always be had in London and, to a more limited extent, in some other English markets, if not for its official price of £3. 17s 10.5d then for something not far from it. In that case, the main disadvantage consisted of transport costs amounting, in the case of shipments to Scotland, of between half and three-quarters of one percent of the purchase price, plus a fixed insurance fee.

The Great Blockade

In the fall of 1808 circumstances changed radically, thanks mainly to the delayed effects of Napoleon’s Continental System, which had closed the European market to British exports two years before. For the first time gold commanded a substantial premium that peaked at over 40 percent during the last half of 1813. Under the circumstances — and the British government’s contrary official stance notwithstanding — it would be ludicrous to maintain that the public, whether in Scotland or elsewhere where the suspension remained in effect, continued to regard banknotes as equivalent to gold.[4]

Yet it would be a mistake to assume that the harm done to Scottish and other holders of banknotes and deposits was proportional to the extent to which the price of gold rose above its par value. By 1808 the “paper pound” had been an established fact for more than a decade, making it extremely doubtful that many contracts were still being entered into on the assumption that the payments called for would be made in anything save paper money and token coin. The “promise to pay” that every banknote bore was likewise understood to mean nothing more than a promise to replace one specimen or type of paper money with another.

Under these circumstances, it was only reasonable for merchants and laborers to determine what they regarded to be the right sums, not of gold but of banknotes themselves, to demand in exchange for their merchandise and labor, while allowing for the risk that paper would fall in value relative to gold. And it was likewise only reasonable for persons who deposited either silver or gold in a bank to determine whether the promised return — here, again, understood as a return likely to be paid in paper money — was sufficient to make the deposit worthwhile. Finally, it was possible for many who distrusted the paper standard to protect themselves by trading bank money for gold while it was still at or close to par, albeit by sacrificing the interest return banks promised them. In short, although there’s no doubt that many were caught short by the unprecedented post-1808 increase in the price of gold, and still greater increase in prices more generally, the overall losses attributable to that increase were presumably far less than those that would have ensued from an otherwise equivalent but immediate devaluation of a previously convertible currency.

Scotland’s Small Change Problem

The appreciation of gold after 1808 was, on the other hand, not the only source of anguish stemming from the banks’ decision to suspend specie payments. Besides denying bank liability holders ready access to gold at its official price the suspension denied them access to silver; and although gold rather than silver had been Great Britain’s de facto medium of account, it was lack of access to the less precious metal that proved particularly troublesome to many bank customers, and especially to merchants and manufacturers of all kinds. For those merchants and manufacturers needed small-denomination media with which to make change and pay their workers; and because banknotes were generally available only in larger denominations, they couldn’t serve the purpose even if they were still worth their nominal value in gold.

The problem was especially acute in England, where the smallest notes issued either by the Bank of England at the onset of the crisis were for £5 — a princely amount when you consider that the average wage worker was lucky to bring in 10 shillings a week, or one-tenth that amount! It was mainly owing to their fear of being deprived of means of payment suitable for their everyday needs, including gold guineas and half-guineas as well as smaller silver coins, that the English public panicked upon learning of the restriction. “It is no exaggeration to say,” writes William Graham, “that had the Bank of England at this time issued one pound notes…the storm would have been prevented.” The panic, he adds, “was purely a scarcity of a suitably small circulating medium in which the public could have confidence, and not a commercial crisis in any sense.”[5]

It was only after panic had set in, in March 1797, that the Bank first issued £1 notes, thereby helping to relieve the small-change problem and, ultimately, to bring more specie out of hiding and into its coffers. Eventually English and Welsh country banks, which had also been prevented from issuing notes of £5 or more, were also granted permission to issue £1 and £2 notes, thereby providing further relief. Coin remained necessary, however, for amounts below £1, causing numerous other expedients, including private tokens, to be resorted to in lieu of official silver coins.[6]

In Scotland the situation was better in so far as banks there were already allowed to issue £1 notes when the crisis broke out. Consequently the panic was largely limited from the start to a scramble for smaller-denomination silver coins. In Memoirs of a Banking-House, Sir William Forbes, who was then head of Forbes, Hunter and Co. (forerunner of the Union Bank of Scotland) offers a vivid account of the situation he and other Edinburgh bankers confronted then. The bankers having plastered the city with handbills and notices announcing their decision to suspend, the counting house of Forbes, Hunter and Co. at once found itself

crowded to the door with … fishwomen, carmen, street-porters, and butchers’ men, all bawling out at once for change, and jostling one another in their endeavors who should get nearest to the table, behind which were the cashier and ourselves endeavoring to pacify them as well as we could. … [W]e felt the hardship on the holders who were deprived of the means of purchasing with ready money the necessaries of life, as there were no notes of less value than twenty shillings, and it was with the utmost difficulty they could get change anywhere else; for the instant it was known that payment in specie were suspended, not a person would part with a single shilling that they could keep, and the consequence was that both gold and silver specie was hoarded up and instantly disappeared. …Saturday was the day on which we had the severest outcry to encounter; for on that day we had always been accustomed to the largest demand for silver to pay wages.[7]

“The banks,” William Graham writes, “were besought to issue smaller notes than for one pound,” but were prevented from doing so by the Bank Notes Act of 1765. Instead “recourse was had to tallies, tokens, and sometimes even to tearing a twenty-shilling note into quarters, for which the bankers afterwards freely paid the proportional sum.”[8]

But in March Parliament, having relieved the situation in England and Wales somewhat by allowing banks there to issue £1 notes, in turn brought relief to Scotland by suspending the provision of the 1765 Act outlawing Scottish bank notes for less than that amount. Before long, substantial quantities of banknotes worth as little as 5 shillings had fully met Scotland’s demand for small change, bringing the Scottish panic to an end, and eventually causing large amounts of silver coin that had disappeared into hoards returning to circulation, if not to Scottish bankers’ coffers. According to Sir William Forbes,

It was remarkable…after the first surprise and alarm was over, how quietly the country submitted, as they still [1803] do, to transact all business by means of bank-notes, for which the issuers give no specie as formerly. The wonder was the greater, because the act of the Privy Council first, and afterwards the act of parliament, applied merely, as I have already said, to the Bank of England, while all other banks, both in England and Scotland, were left to carry on their business without any protection from parliament, and without any means of obtaining specie beyond what the natural course of business brought into their hands from the circulating in the country. That source, however, has hitherto proved amply sufficient for all needful purposes (my emphasis).[9]

***

With the facts concerning the causes and consequences of the Scottish suspension before us, we’re now prepared to consider the extent to which that suspension ought to be regarded as a black mark against the Scottish free banking system, if not against freedom in banking more generally. I’ll address that topic in my third and final post in this series.

_______________________

[1] Although Great Britain did not officially switch from bimetallism to a gold standard until 1819, a de facto gold standard is generally understood to have prevailed there since the opening decades of the 18th century when, by assigning gold guineas an official value of 21s Isaac Newton caused gold to be legally overvalued at the Royal Mint relative to silver.

[2] Henry Adams, “The Bank of England Restriction. 1797–1821,” North American Review, Vol. 105, No. 217 (Oct., 1867), pp. 402–3. Reprinted in Charles Francis Adams Jr. and Henry Adams, Chapters of Erie, and Other Essays (Boston: James R. Osgood and Company, 1871), pp. 224–68.

[3] William Graham, The One Pound Note in the Rise and Progress of Banking in Scotland (Edinburgh: James Thin, 1886) p. 123.

[4] Yet Nicolas Vansittart denied it nonetheless, by moving a resolution in Parliament in 1811 to the effect that the public then considered banknotes to be equivalent to gold. By so doing he made a laughing stock of himself. Still that didn’t stop Parliament from passing the resolution.

[5] Graham, op. cit., p. 115.

[6] For the story of the private tokens issued during this period see my Good Money: Birmingham Button-Makers, The Royal Mint, and the Beginnings of Modern Coinage, 1775–1821 (Ann Arbor and Oakland: University of Michigan Press and the Independent Institute, 2008).

[7] Sir William Forbes, Memoirs of a Banking-House (London: William and Robert Chambers, 1860), p. 81.

[8] Graham, op. cit., p. 116.

[9] Forbes, op. cit., p.85.