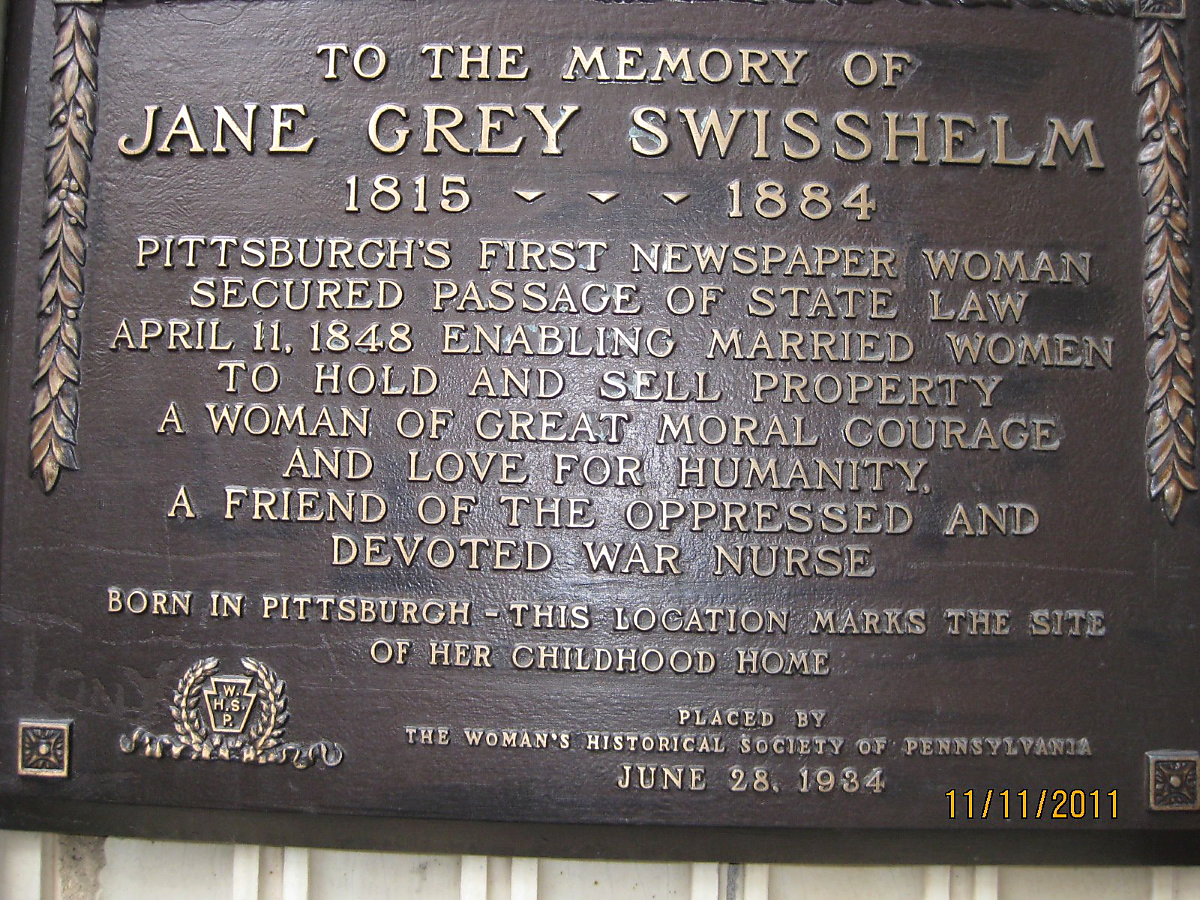

On August 26, 1920, the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, giving women the right of the vote, was formally certified. In 1973 Congress designated August 26 as Women’s Equality Day. Equal suffrage is one part of equality under the law, but by no means the only part. Visiting Pittsburgh a few years ago I came across this historical marker:

Anyone who thinks Americans were free in some earlier period might want to ponder the message on the plaque, which celebrates the woman who persuaded the legislature in 1848 to allow married women to own and sell property. (Court decisions, however, limited these rights, including declaring that earnings were not “property.”) As Charles O’Brien wrote in the American Law Register in 1901, in an article titled, “The Growth in Pennsylvania of the Property Rights of Married Women,”

Whether these criticisms are sound or not, the practical results were as stated, and in substance her property and contractual rights as a single woman were almost entirely destroyed, her legal existence for most purposes suspended. and other legal disabilities not to be properly considered here added to her estate when she became a married woman. Such legal servitude was incompatible with the spirit of the founders of the Commonwealth and their descendants.

Throughout the 19th century states began to change those laws, though other legal disabilities for women remained.

The cause of women’s rights has always been bound up with the spread of classical liberalism. In England the liberal writer Mary Wollstonecraft responded to Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France by writing A Vindication of the Rights of Men, in which she argued that “the birthright of man … is such a degree of liberty, civil and religious, as is compatible with the liberty of every other individual with whom he is united in a social compact.” Just two years later she published A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, which asked, “Consider … whether, when men contend for their freedom … it be not inconsistent and unjust to subjugate women?”

In the United States the ideas of the American Revolution — life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness — led logically to agitation for the extension of civil and political rights to those who had been excluded from liberty. Women involved in the abolitionist movement also took up the feminist banner, grounding their arguments in both cases in the idea of self-ownership, the fundamental right of property in one’s own person. Angelina Grimké based her work for abolition and women’s rights explicitly on a Lockean libertarian foundation: “Human beings have rights, because they are moral beings: the rights of all men grow out of their moral nature; and as all men have the same moral nature, they have essentially the same rights.… If rights are founded in the nature of our moral being, then the mere circumstance of sex does not give to man higher rights and responsibilities, than to women.” Her sister, Sarah Grimké, also a campaigner for the rights of enslaved persons and women, criticized the Anglo-American legal principle that a wife was not responsible for a crime committed at the direction or even in the presence of her husband in a letter to the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society: “It would be difficult to frame a law better calculated to destroy the responsibility of woman as a moral being, or a free agent.” In this argument she emphasized the fundamental individualist point that every individual must, and only an individual can, take responsibility for his or her actions.

The Declaration of Sentiments adopted at the historic Seneca Falls Convention in 1848 consciously echoed both the form and the Lockean natural-rights liberalism of the Declaration of Independence, expanding its claims to declare that “all men and women are created equal,” endowed with the inalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. The document notes that women are denied moral responsibility by their lack of legal standing and concludes that women have been “deprived of their most sacred rights” by “unjust laws.” Consider some of the specific grievances relating to the concerns commemorated in the Pittsburgh plaque:

He has made her, if married, in the eye of the law, civilly dead.

He has taken from her all right in property, even to the wages she earns.

After depriving her of all rights as a married woman, if single and the owner of property, he has taxed her to support a government which recognizes her only when her property can be made profitable to it.

He has monopolized nearly all the profitable employments, and from those she is permitted to follow, she receives but a scanty remuneration.

He closes against her all the avenues to wealth and distinction, which he considers most honorable to himself.

That classically liberal, individualist strain of feminist thought continued into the twentieth century, as feminists fought not just for the vote but for sexual freedom, access to birth control, and the right to own property and enter into contracts.

A libertarian must necessarily be a feminist, in the sense of being an advocate of equality under the law for all men and women.