Back in May 2009, Paul Krugman published a column titled “The Big Inflation Scare.” In it, he complained about the “inflation fear-mongering” going on at the time.

“Suddenly,” Krugman wrote, “everyone is talking about inflation. Stern opinion pieces warn that hyperinflation is just around the corner. …But does the big inflation scare make any sense? Basically, no … Deflation, not inflation, is the clear and present danger.”

I know that many faithful Alt‑M readers aren’t exactly big Paul Krugman fans. But let’s face it: despite a quadrupling of the size of Fed’s balance sheet by 2015, and persistently low interest rates, Krugman was right, and the inflation mongers were wrong. If the Fed has failed to meet its objectives since the last crisis, it’s done so not by exceeding, but by consistently falling short of, its chosen inflation target.

Wolf!

You might think that the utter failure of the last round of high-inflation forecasts would make even die-hard inflation mongers think twice about declaring that, because interest rates are back to zero, and the Fed’s balance sheet is ballooning again, high inflation must be just around the corner.

No such luck. Even setting aside professional doomsayers who predict hyperinflation as often as clocks strike midnight, pundits are starting once again to treat the Fed’s emergency measures as a near guarantee of severe inflation to come.

Two recent op-eds, both by traditional (as opposed to “market”) monetarists, illustrate the resurgence. In National Review, Martin Hutchinson writes:

If you think too much money creation causes inflation, we will get inflation. If you think budget deficits cause inflation, we will get inflation. If you are old-fashioned enough to think that rising costs and increasing economic inefficiency cause inflation, we will get inflation. It really doesn’t matter which economic theory you subscribe to, they all arrive at the same destination—more inflation.

After reminding us of Milton Friedman’s famous claim that “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon,” Hutchinson goes on to observe that

In the six weeks to April 6, M2 money supply has increased by 7.7 percent, an annual compounded rate of 90.4 percent. That reflects all the money the Fed has pumped into the system; the statistics are not wrong. But at that rate of money creation, if Friedman is right, we should get inflation close to triple digits, 18 to 24 months from now. You can’t produce money at that rate without the dollar going the way of the continental, the assignat, the reichsmark or the 1946 Hungarian pengo, exchanged for the new forint at a conversion rate of 1029 to 1.

A day later, economist Tim Congdon voiced the same concerns in the Wall Street Journal. In its efforts to avoid another Great Depression, he says, the Fed

has poured money into the economy at the fastest rate in the past 200 years. Unfortunately, this overreaction could turn out just as poorly; history suggests the U.S. will soon see an inflation boom.

Like Hutchinson, Congdon appeals to money growth statistics in making his case. “It’s reasonable to assume,” he says,

that by spring 2021 the quantity of money will have increased by 15% and possibly by as much as 20%. That wouldn’t quite match the peak rates of expansion seen during and immediately after the two world wars of the 20th century, but it could surpass peacetime records, outpacing the previous peaks in the inflationary 1970s.”

That’s not nearly as scary as Hutchinson’s forecast. But it’s scary enough.

Once Burnt, Not Shy At All!

The problem with such forecasts isn’t just that they rest on oversimplified theories. It’s that they rest on precisely the same oversimplifications that caused so many similar forecasts to fall flat years ago.

In Hutchinson’s case the error is especially hard to excuse, for he was among those whose previous predictions went so badly awry. In April 2009, Hutchinson wrote that U.S. policies resembled “those of Germany during the period between 1919 and 1923”:

U.S. authorities probably won’t pursue expansionary monetary policies with quite the dogged Germanic persistence that caused the mark to fall to one trillionth of its former value. However, the turnaround needed to stop a Weimar repetition will be very unpleasant, so there will undoubtedly be considerable denial and fudging of the figures as inflation begins to take off.

That sounds dismayingly familiar. What’s more, in his recent article Hutchinson recognizes that the naive monetarist reasoning on which both of his predictions depend was at least partly to blame for his earlier failure. “In the ten years to February 2020,” he says, although the M2 money stock grew at an annual rate of 6.3 percent,

we did not get the inflation that was promised. Nominal GDP grew only 4 percent per annum in the ten years to the fourth quarter of 2019, so the other 2.3 percent per annum of money supply got lost somewhere. …For the ten years before the coronavirus, therefore, Friedman’s central principle did not work; we should have had about 4 to 5 percent inflation rather than the 2 percent we actually got.

So what “central principle” does Hutchinson rely on for his forecast this time? Why, the very same one! Having met Mr. Hutchinson, and enjoyed some of his other writings, I doubt anyone could consider him less than perfectly sane. But he certainly appears to be guilty of doing the same thing over again and expecting a different result.

And Some Elephants

Unlike Hutchinson, Tim Congdon worried not about inflation but about deflation in 2009. He also wrote in favor of the Bank of England’s efforts to combat it, and did so despite the fact that the growth rate of the U.K.‘s M2 money stock was then (July 2009) 10 percent, and would soon reach 15 percent. (The U.K. inflation rate, in the meantime, went from just under 2 percent in 2009 to a post-2008 peak of almost 4 percent in 2011, casting doubt on whether the Bank of England really needed to “keep the money flowing to stave deflation.” Still, 4 percent inflation was far from exorbitant by British standards.) Yet Congdon now considers a 15 percent M2 growth rate dangerously high for the U.S., while otherwise embracing the same quantity-theoretic reasoning Hutchinson uses to determine where prices are headed.

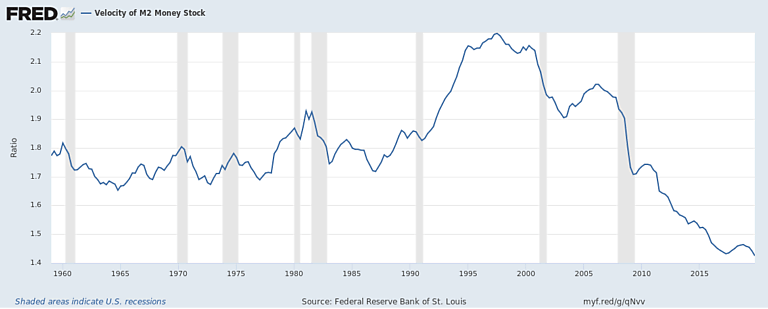

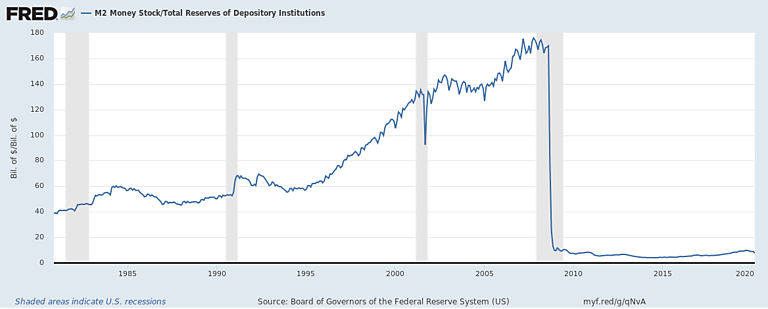

But that reasoning, which rushes straight from money growth rates to likely inflation, rests on assumptions that are just as false today as they were in 2009. One of these is that the velocity of M2 and other broad money representations—the rate at which the money in question gets exchanged for goods and services—hasn’t declined substantially. Another is that the reserve “multiplier”—the ratio of the quantity of broad money to the stock of bank reserves—hasn’t itself declined.

That both of these assumptions are false ought by now to be notorious. But for those who aren’t convinced, the following two FRED charts should suffice to drive the point home:

Fukuyama may have been wrong to declare “The End of History” according to his particular understanding of the term. But there’s a real sense in which we have witnessed the end of monetary history as Friedman and Anna Schwartz understood it—that is, as a story of the systematic influence of particular monetary aggregates on output and employment. And I say so as an ardent fan of both of them.

That the old connection between growth in bank reserves and growth in broad money measures has been severed for more than a decade is never so much as hinted at in Congdon’s op-ed. Nor does the word “velocity” turn up in it. Hutchinson likewise seems unaware of how dramatically these determinants of inflation have changed. Although he does mention velocity, what he says about it is worse than nothing:

Monetary economists wave their hands and talk about “velocity,” but monetary velocity is supposed to increase, not shrink, as our payments systems get more efficient.

Consider: a chart showing a dramatic decline in velocity, and a writer saying that it’s “supposed” to go up, and ask yourself whose hands are waving.

Is This Time Different?

Of course history isn’t exactly repeating itself: as Mark Twain might say, it is at best only rhyming. Perhaps some of the variations are enough to make inflation a real threat this time. Still I doubt it.

Three differences that might seem to warrant renewed inflation fears are (1) the fact that this crisis involves an adverse supply shock; (2) the anticipated scale of the Fed’s balance sheet growth; and (3) the correspondingly huge anticipated increase in the federal debt. Let’s consider each in turn.

As David Andolfatto explains, the coronavirus “clearly fits [the] bill” of a negative “supply shock,” meaning an event that lowers “society’s ability to produce goods and services.” Negative supply shocks mean higher prices, other things equal. It follows that, if all we were experiencing were a supply shock, we’d be watching prices go up.

But the coronavirus crisis isn’t just a supply shock: it involves combined, negative supply-and-demand shocks, where one tends to pull prices up, and the other tends to pull them down. And, so far, the demand shock has been winning that tug-of-war: according to the BLS, the CPI fell 0.4 percent in March—its biggest one-month decline since January 2015. Nor are market participants expecting more inflation in the future. On the contrary, the 5 Year TIPS/Treasury breakeven rate—a measure of investors’ inflation expectations—is just 0.69 percent.

As for the magnitude of the Fed’s operations, the Fed’s rapidly-expanding balance sheet is now expected to level-off at about $8 trillion, or somewhat less than twice its previous post-2008 peak. That’s a heck of a lot of Fed dollars. But how much does it matter? Thanks to what David Beckworth calls “The Great Divorce”—the 2008 change that undid the long-standing connection between the quantity of bank reserves and the broad money supply—the answer is, not much. Instead, any stimulus effects of Quantitative Easing depend, not on banks’ making use of fresh reserves that come their way, but on the effect of the Fed’s asset purchases on long-run interest rates. And those effects, to judge by the 2009–15 experience, are likely to be very modest.

Finally, the debt. Greg Ip covers this so well that I need only summarize what he’s written. Credible estimates, he says, put the accumulated deficits at 106 percent of GNP, matching a record set in 1946. But that doesn’t mean we’re bound to experience World-War-II-level inflation, let alone hyperinflation. Although governments sometimes choose to deal with debts they’d otherwise be hard-pressed to pay through debt monetization and consequent inflation, and investors fearing this will shy away from their securities, that’s a far cry from what’s happening now. Instead, Ip notes, “The Fed’s target federal funds rate is effectively zero, and 10-year Treasury yields are below 1% for the first time.” Consequently, for the time being at least, it’s actually relatively easy for the U.S. government to manage more debt.

Never Say Never

Don’t get me wrong: I’m not saying that we have no reason at all to fear a recrudescence of high inflation some time in the future. Inflation may be knocked-out for now; but that doesn’t mean it’s dead. I’m neither optimistic nor pessimistic enough to suppose it will never spring back to life again. Furthermore, even before the present crisis I perceived threats to the Fed’s already tenuous independence that could eventually undermine its commitment to low inflation. The extraordinary duties the Fed has since taken on only heighten my fears. As Olivier Blanchard has recently observed, the “fiscal dominance” of monetary policy, in combination with a very large debt to GDP (or GNP) ratio, and a rising neutral interest rate, could cause “a future Fed, with a chair appointed by a populist president… to bend and keep rates low for too long, leading to overheating and inflation.” Although Blanchard adds that the risk that this will happen “is very small,” it would be imprudent to overlook it altogether.

But if denying any risk of future inflation is unwise, so is exaggerating that risk, or claiming that it’s imminent when it isn’t. Instead of supplying a useful warning, such false alarms encourage people to treat high inflation, not as a real if still distant possibility, but as a bogeyman. And that’s asking for trouble: the villagers didn’t suffer because they listened to the boy who cried wolf. They suffered because they decided to ignore him.