The great development economist Deepak Lal, a colleague and long-time friend to many of us at the Cato Institute, passed away at his home in London yesterday. He was 80 years old. Deepak was one of the most accomplished and impressive scholars I’ve had the privilege to know and to work with. I will miss his friendship and support dearly.

Although he was a trained economist, Deepak believed in an interdisciplinary approach to the study of developing countries. His scholarship was original, erudite, and prolific, producing more than a dozen books published by the most prestigious academic presses in the world. He taught at Oxford, University of London and UCLA, and had served as president of the Mont Pelerin Society. But he was also a development practitioner, which took him to most developing countries, and he had not always been a classical liberal. In the 1960s he joined the Indian foreign service and in the 1970s he served on the Indian Planning Commission. He consulted extensively with international organizations. It was during this time that he became disenchanted with planning bureaucracies and their approach to development. Decades later he would write: “It is my practical experience in working in … developing countries which has led me to the views I now hold.”

Going against the mainstream in his field, Deepak summoned the most powerful evidence and argumentation against what he called the “dirigiste dogma.” His book, The Poverty of “Development Economics,” published by the Institute of Economic Affairs in 1983 and subsequently revised and expanded, is still one of the best critiques available of the thinking that dominated, and to some degree still informs, development economics. There and in subsequent publications, Deepak would harshly critique such notions as the vicious circle of poverty, the necessity of foreign aid, industrial policy, protectionism, equality of outcomes, and various ethical problems he identified with constructivist approaches to development.

Indeed, the “technocratic public economics approach to public policy” as he put it, “is ahistorical, suffers from amnesia concerning the history of economic thought, is ideological insofar as it sets up egalitarianism as a self-evident objective of public policy, is institutionally impoverished and, most seriously, makes assumptions about the character of most governments which—to put it mildly—are not universally valid!”

By the time Deepak joined the World Bank in 1983, where he ran major research programs for several years, he had become one of the lone but effective voices for market liberalism in the developing world. Deepak knew the Bank played a powerful role in shaping ideas even if he did not believe in its lending activities. (Like other classical liberals, he believed that the Bank and other multilateral lending agencies should be abolished.) The research and publications that he and his colleagues produced at the Bank made the case for trade liberalization in the developing world that poor countries began following within the next decade.

With the collapse of communism and central planning, economic freedom in much of the developing world notably increased, and The Economist magazine stated, “In the 1990s Lord Bauer and economists such as Anne Krueger, Bela Belassa, Deepak Lal and Ian Little are regarded—above all, in the third world itself—as largely vindicated.”

I got to know Deepak in the 1990s. But his association with Cato reached much further back, as did his friendships with my colleagues Jim Dorn and Bill Niskanen. Since then, Deepak spoke at numerous Cato conferences in Washington and abroad and we’ve had the benefit of publishing numerous of his publications. His 2013 Cato book, Poverty and Progress: Realities and Myths about Global Poverty, describes how the world’s poor are catching up to the rich in terms of well-being and is consistent with the work at our HumanProgress.org project.

It is impossible to summarize the scope, much less describe the depth, of Deepak’s work in a short note. In my view, his most interesting contributions since the collapse of communism focused on the rise of the West and the more recent rise of India and China. He took a very long view of history and the interaction of factor endowments, culture, and politics to explain those ascents and his belief that countries around the world can achieve modernization without westernization. That’s an encouraging message to other societies that don’t wish to undergo wholesale cultural change in order to achieve material progress. But Deepak was also concerned with decay in Western society. He warned that “It is by no means self-evident…that Western democracy necessarily promotes a culture which is market friendly.”

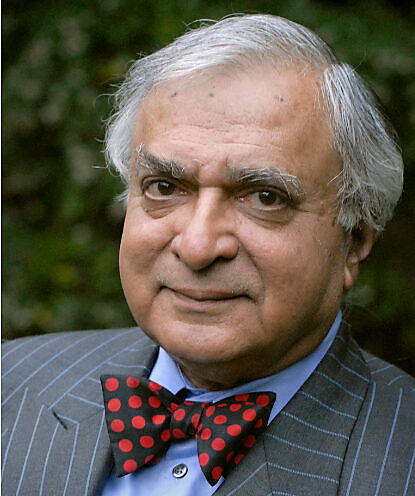

Quite so. Still, Deepak was actively engaged till his last days in promoting market-oriented policies in Western and non-Western countries alike, just as he had done most of his life. I will miss my regular exchanges with him, and Jim Dorn and I will miss having dinners with him and his wife Barbara during their yearly visits to Washington. (That’s Deepak, Jim and me in the adjacent picture at a lunch we had during his last trip to DC.) Our heartfelt thoughts go out to Barbara and the family.