Downtown San Francisco may be in for an extended period of reduced office occupancy resulting in lower revenue for local government. While it is tempting to view the current downturn as cyclical, there are reasons to believe any rebound will be long in coming. That being the case, San Francisco’s public sector should start downsizing now to avoid a fiscal crisis later.

The shift to remote work and the more recent round of tech layoffs have taken an especially heavy toll on San Francisco. Kastle Systems’ back-to-work barometer recently showed San Francisco office occupancy at 41.6% of pre-pandemic levels compared to an average of 47.5% across the ten major markets the company tracks.

In a recent Bond Buyer article, Economist Christopher Thornberg expressed the conventional, optimistic long-term view of the San Francisco tech economy. Reflecting on the collapse of the turn-of-the-century dot-com bubble:

People said then that San Francisco would empty out, but the tech industry came back in the next few years, even stronger…Keep in mind in 2000, there were 550,000 tech jobs in San Francisco before the tech market collapsed … Everyone wondered what would happen. Ten years later, there were 750,000 tech jobs.

But there are a couple of reasons to think that a similar rebound this time is not in the offing. First, in 2000, the internet was still at a nascent stage. Today, most people in the developed world have some form of high-speed internet access, and most people in the developing world can experience the internet on inexpensive older-generation smartphones. With so many people already connected and already engaging with online content for several hours each day, the room for further growth is limited, and thus the tech sector rebounding to a higher level is less likely.

Meanwhile, recent events at Twitter are raising a red flag for tech employment prospects. Under Elon Musk, the company has shed over half its workforce and is still serving a record number of users. If Twitter gets through the current turmoil without taking an extended outage, it will send a signal to other large tech companies that they are overstaffed. Management at these firms may respond with more layoffs, attrition, and hiring freezes. If management is not inclined to make these changes, it will face pressure from Wall Steet to do so.

On the other hand, Musk is an opponent of remote work. If other firms follow his lead in demanding office attendance, more workers may return to downtown San Francisco. But the city could also see the worst of both worlds: lower employment by tech firms and a low percentage of those still employed coming into the office.

A prolonged downturn in office utilization will adversely impact several local government revenue streams. Office buildings will be reassessed at lower valuations, reducing property tax receipts. Fewer commuters shopping at downtown stores and dining at downtown restaurants will reduce sales tax revenues. Fewer bus and rail riders will translate into lower fare revenues. Divided government in Washington is likely to mean less federal grant revenue, while the State of California’s less optimistic revenue forecasts could mean less state aid, especially for local schools.

These circumstances may force the city’s public sector to go on a diet. Up until now, surging tax receipts combined with generous state and federal aid have supported high levels of local spending. This year, San Francisco’s combined city and county government has an overall budget of $13.95 billion, which covers general fund spending as well as the publicly owned airport and other municipal enterprises.

But some governmental services are provided by independent entities, including San Franciso Unified School District, City College of San Francisco, the San Francisco Housing Authority and the Transbay Joint Powers Authority, which runs the multi-billion-dollar bus terminal that recently opened downtown. When the budgets of these four entities are added to the city/county budget, total spending reaches $15.53 billion, or over $19,000 per resident. Even this number fails to cover all local government spending because it does not include regional entities such as the San Francisco Bay Area Regional Transportation Authority (BART).

While San Francisco’s government seems expensive in absolute terms, comparative analysis is challenged by differences in local government structure across the United States. Unlike most major cities, San Francisco’s County and municipal governments are consolidated. Among cities of comparable size, only Jacksonville, FL and Nashville, TN have a similar structure.

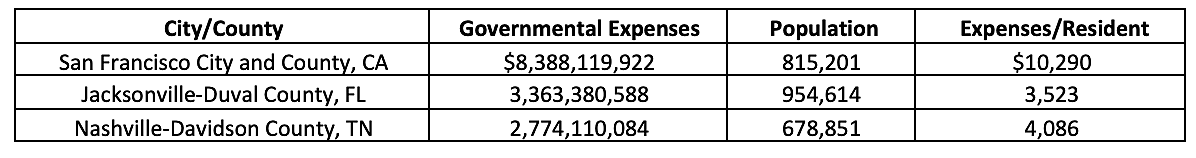

Comparing Fiscal Year 2021 audited financial statements for the three entities, excluding enterprise funds and including school district expenses yields the following comparison:

This analysis shows that the cost of core local government services per capita in San Francisco is more than 2.5 greater than its city/county peers. That said, it is worth noting that the cost of living is far higher in San Francisco than in the Southeastern U.S., so it may not be reasonable to expect San Francisco to operate at similar cost levels.

But anecdotal evidence suggests that San Francisco government is inefficient. Among these anecdotes are stories of $20,000 trash cans, $1.7 million public restrooms, a $1.9 billion two-mile underground light-rail line, and affordable housing projects costing more than $1 million per unit. On a macro level, the municipal government has a homeless budget exceeding $1 billion, yet the city continues to face a homelessness crisis.

San Francisco’s dynamic tech-powered economy has been able to afford these excesses for many years. But with revenues starting to fall, the time has come to find cost savings. If downtown tech employment and the government revenues it generates are indeed going to be lower over the long term, it will be far better to economize on government now than to kick the can down the road. Maintaining high spending in the face of declining revenues would require overt or covert borrowing to cover operating costs, a bad fiscal practice that shifts the burden onto future residents.

Instead, local leaders should consider initiating a Zero-Base Budgeting (ZBB) process that would require all departments to justify each of their activities. Rather than base subsequent year budgets on prior year spending, ZBB begins with a base of zero. Perhaps the thorough examination of all spending that this exercise requires will bring some discipline to San Francisco government spending.