The trade balance is calculated as the difference between the value of U.S. exports and the value of U.S. imports. The United States “runs a trade deficit” when Americans purchase more goods and services from foreigners than foreigners purchase from Americans.

To be more precise, the trade deficit is the amount by which the total value of purchases of U.S. consumers, businesses, and governments from foreign suppliers exceeds the total value of purchases of foreign consumers, businesses, and governments from U.S. suppliers.

The trade deficit gets a lot of negative attention. It’s got a bad reputation—probably because it’s called a “deficit.” Sounds like something that needs fixing. But the truth is that the trade deficit has a lot going for it. It’s just, well, misunderstood.

Over the years, my colleagues and I have written extensively about the real meaning of the trade deficit; that it is not a reflection of trade policy; that it is to be expected for a country whose government issues the world’s primary reserve currency; and that the dollars that go abroad to purchase imports find their way back into the U.S. economy in the form of investment in equities, real estate, factories, other structures, equipment, and corporate and government debt; and that the only portion of that capital inflow from foreigners that current and future taxpayers need to repay is the principal and interest on government debt (which implicates fiscally irresponsible government, not trade).

President Trump, Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross, White House adviser Peter Navarro, and others in the administration don’t seem to get this. They see trade a zero sum game, with exports as Team America’s points, imports as the foreign team’s points, and the trade account as the scoreboard. The deficit on that scoreboard (the trade deficit) means that Team America is losing at trade and it’s losing because the foreign team—much like the Houston Astros—cheats.

The misguided objective of trade policy for the past three years has been to minimize imports and maximize exports. And the tools deployed in pursuit of these objectives—sweeping tariffs, withdrawal from a major trans-pacific trade agreement, wanton subversion of the international rule of trade law, and compelling partners into renegotiations of trade agreements under the barrel of a gun—have failed to eliminate (or even reduce) that trade deficit. In fact, between 2016 and 2019, the goods deficit increased from $735 billion to $853 billion. That said, the administration is likely to make progress toward that goal this year because U.S. trade deficits decline during economic contractions.

But there’s a better way to think of the meaning of the trade deficit. Milton Friedman liked to point out that exports are things we produce but don’t get to consume, while imports are things we consume without having to produce. Yet, when Americans get more stuff from foreigners than foreigners get from Americans, it’s called a “deficit.” Go figure!

If you happen to use toilet paper, the following example may resonate.

In 2019, U.S. producers exported over 72 million kilograms (about 802 million rolls) of the supple utensil to be deployed by people in other countries. WHAT? HOW COULD THEY? DON’T THEY KNOW HOW MUCH WE LOVE TP IN AMERICA? Indeed, we do (no pun)!

According to Statista.com, the United States leads the world in toilet paper consumption, averaging 141 rolls of the fluffy stuff per person per year. So, the precious supply that U.S. producers exported last year could have sated the derrieres of some 5.7 million Americans. Juxtapose that stat against the wrestling matches you’ve witnessed in your grocer’s paper products aisle.

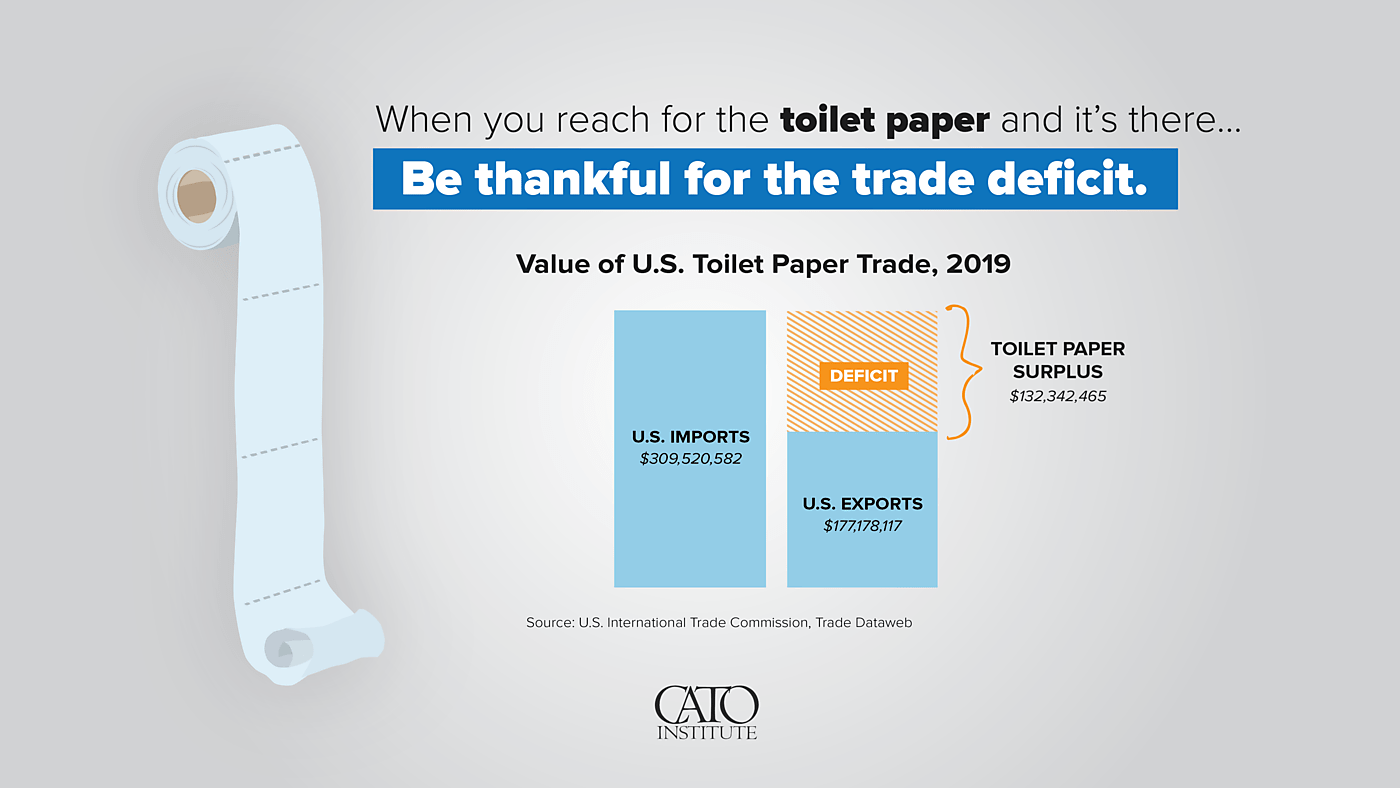

But here’s the thing. In 2019, not only was toilet paper shipped abroad. It was also imported—and in vastly more significant sums. Volumes of over 194 million kilograms or nearly 2.2 billion rolls were imported last year, satisfying the demands of approximately 15.6 million Americans. In other words, international trade in 2019 produced a net surplus of about 1.4 billion rolls of toilet paper (2.2 billion rolls imported minus 0.8 billion rolls exported) for people in the United States. Trade helped meet the toilet tissue demands of a net 10 million Americans. That’s 10 million fewer people poised to rumble in the aisles of Target and Walmart.

Unfortunately, the trade statistics aren’t recorded in a way that illustrates the facts that Milton Friedman shared with us. They record the dollars that changed hands, not the number of rolls put to good use. But at the end of the day (and, throughout the day), we know which paper ultimately serves the purpose we demand.