The Supreme Court hears arguments today regarding the ability of state governments and their labor unions to extract union fees from unwilling employees. The case involves an Illinois state worker who decided not to join the AFSCME union that covers his job, but is being forced to pay a $45 per month “agency fee” to the union nonetheless.

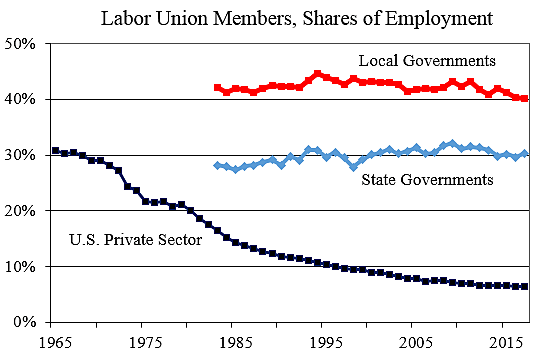

Illinois is one of 23 states that allow unions to impose agency fees on nonmembers. The other 27 states allow people the “Right To Work” without unions picking their pockets. There has been a shift toward Right to Work in recent years, but the chart below shows that while union membership has plunged in the private sector, it has remained high in state and local governments.

Prior to the 1960s, unions represented less than 15 percent of the state-local government workforce. That changed during the 1960s and 1970s, as a flood of state laws triggered a dramatic rise in public-sector unionism. Many states passed laws that encouraged or required collective bargaining in the public sector, while also imposing compulsory union fees. The chart shows that we had reached today’s high rates of public-sector unionism by the early 1980s, which is when hard data on membership begins.

In 2017, 30.3 percent of state government workers and 40.1 percent of local government workers were union members, compared to just 6.5 percent of workers in the private sector. The combined state-local rate of union membership at 36.1 percent is more than five times higher than the private-sector rate. The most recent BLS data is here.

Why the public-private difference? Public agencies are static—once a union has organized a group of workers they tend to stay organized. By contrast, the private sector is dynamic, with businesses going bankrupt and new businesses arising all the time. Since all new businesses start out as nonunion, greater organizing efforts are needed to sustain private-sector unions.

Another factor is that many government services are legal monopolies, such as police and fire. The result is that consumers do not have the option of abandoning unionized public services if they become too expensive and inefficient, as they can do with unionized services in the private sector.

The Supreme Court case has to do with requiring public-sector employees to pay union fees. However, the more fundamental issue is so-called collective bargaining, or monopoly unionism. In both the public and private sectors, collective bargaining gives unions the exclusive right to speak for covered workers on workplace issues, many of whom may disagree with the union’s views. Dissenting individuals are prevented from dealing directly with their employer, and they cannot choose to be represented by another organization. So workers’ freedom of association is violated not just by mandatory union fees, but by collective bargaining in general.

Exclusive representation is a violation of voluntary exchange. It implies that an individual does not own his labor. Rather, a majority of his colleagues own it. It is a violation of a dissenting worker’s freedom of association. Freedom of association in private affairs requires that each individual is free to choose whether or not to associate with other individuals, or groups of individuals, who seek to associate with him. Freedom of association forbids any kind of forced association, even by majority vote. The sale of one’s labor services to a willing buyer is a quintessentially private act.

The Supreme Court may advance the cause of worker freedom in the current Illinois case, but broader labor union reforms are also needed, as Baird explains here.

For further background on public-sector unions, see here.

For background on collective bargaining see here.

For Cato’s legal brief on the Illinois case, see here.