Tomorrow the U.S. Supreme Court will hear oral argument in Espinoza v. Montana, a case addressing state constitutional provisions that bar public funds from going to religious institutions, especially schools. At the crux of the case is the belief that taxpayers should not be forced to take sides on religion. But the oft-ignored root problem is that public schools cannot be religiously neutral; no matter what they do they are taking sides on religious matters. Only school choice—what has been quashed in Montana—frees the state from that.

The specifics of the case seem minor. The Montana Supreme Court struck down a program offering a $150 tax credit to people who donated to groups furnishing scholarships for students to attend private schools, including religious. As long as religious schools were included, the Montana court ruled that the whole program had to be struck down, lest it violate the state’s constitutional provision—a so-called Blaine amendment—interpreted to prohibit any funds from reaching “sectarian” schools.

At the heart of many people’s concern is entangling government with religion, an absolutely legitimate worry. But as long as there is public schooling—which deals inescapably with minds, and hence worldviews—government will be entangled with religion.

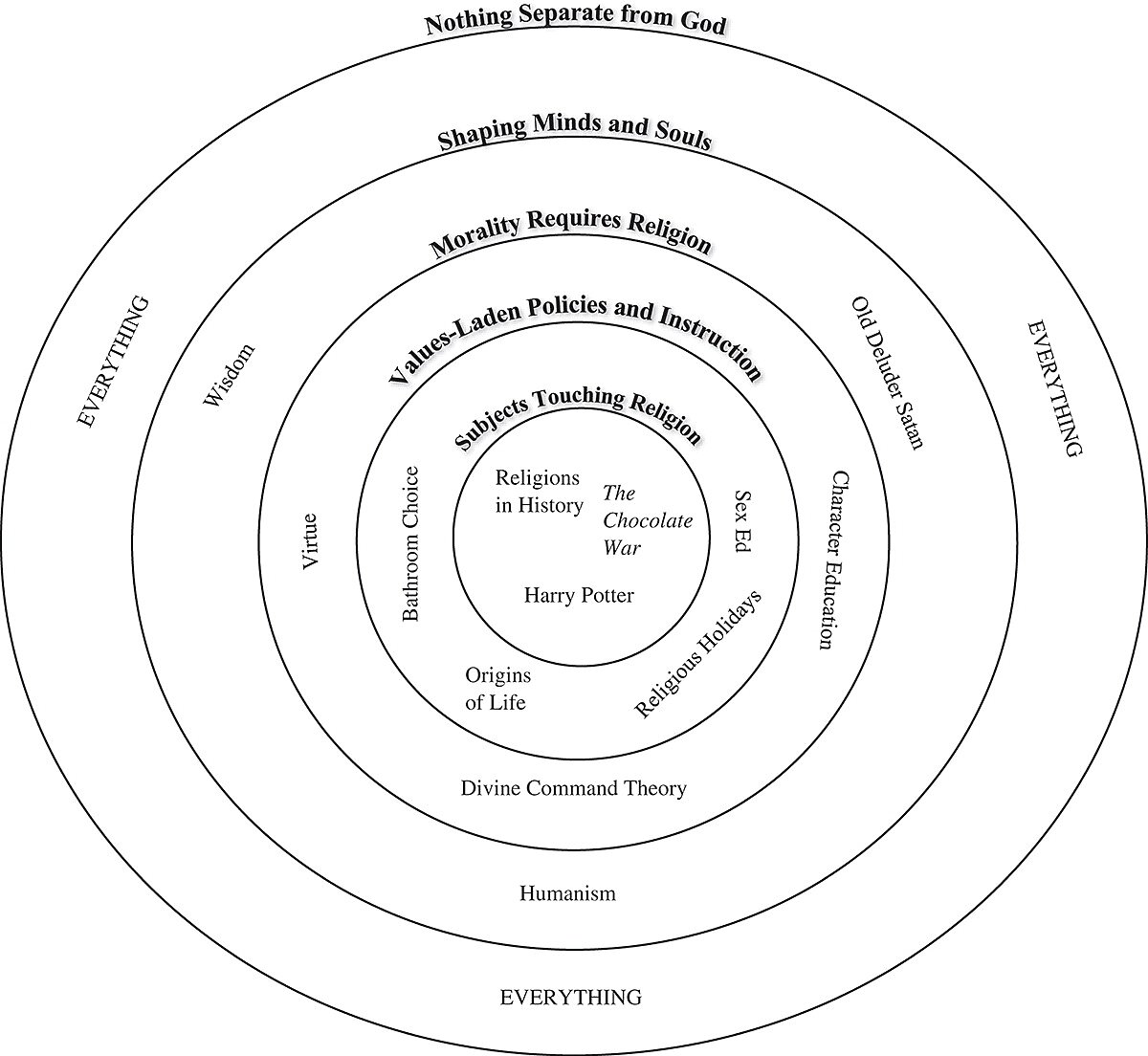

As I illustrate in this Journal of School Choice article—which is also part of a new book on the nexus of education and religion—public schooling has never been, and can never be, religiously neutral. Reproduced below is a graphic I created for the JSC article to help readers understand the many levels on which public schooling intersects with religion. They run from elevating non-religion over religion by the very effort to have religion-free education, to teaching religion-saturated history.

The Public Schooling Battle Map—sadly, still in a state of reconstruction—illustrates that religion remains a powerful flashpoint in public schools. The database contains 346 state- and district-level battles explicitly and foremost about the presence of religion, or perceived affronts to religion, ranging from creationist displays in schools to yoga classes. Many other conflicts may implicate religion, though it may not be the core concern, including battles over bathroom and locker room access being contested nationwide.

Quite simply, religious neutrality in public schools is impossible.

Can government promote education at all without touching on religion? Probably not, but it can come much closer than it does with public schooling. The solution is to do the very thing the Montana Supreme Court struck down: allow people to direct some of their income to groups that provide scholarships, and give them a tax credit. That would enable taxpayers to freely direct their money so that families could choose private schools that may be religious, or to otherwise let it go to public schools. What is crucial is that government no longer force funding of particular schools, and hence particular approaches to faith, rendering the state truly neutral.

There are many reasons the U.S. Supreme Court should rule in favor of school choice. But the most important is that the end that Blaine amendments are supposed to achieve—keeping government out of religion—is far better served by the measure Montana struck down than maintaining a public school monopoly over taxpayer funds.