Back in March, I shared a remarkable study from the International Monetary Fund which explained that spending caps are the only truly effective way to achieve good fiscal policy.

And earlier this month, I discussed another good IMF study that showed how deficit and debt rules in Europe have been a failure.

In hopes of teaching American lawmakers about this international evidence, the Cato Institute put together a forum on Capitol Hill to highlight the specific reforms that have been successful.

I moderated the panel and began by pointing out that there are many examples of nations that have enjoyed good results thanks to multi-year periods of spending restraint.

I even pointed out that we actually had an unintentional — but very successful — spending freeze in Washington between 2009 and 2014.

But the problem, I suggested, is that it is very difficult to convince politicians to sustain good policy on a long-run basis. The gains of good policy (such as what was achieved in the 1990s) can quickly be erased by a spending binge (such as what happened during the Bush years).

Unless, of course, there’s some sort of constraint on the desire to spend money. And the panelists discussed the three most successful examples of reforms that constrain the growth of government.

We started with a presentation by Daniel Freihofer from the Swiss Embassy. He talked about Switzerland’s “Debt Brake,” which actually is a spending cap.

It’s remarkable how well Switzerland has performed while most other European nations have suffered downward spirals of more spending-more taxes-more debt. Here’s a chart I put together on what’s happened to spending in Switzerland ever since 85 percent of voters imposed the Debt Brake early last decade.

By the way, Herr Freihofer said during the Q&A session that support for the Debt Brake is now probably about 95 percent, so Swiss voters obviously understand that the policy has been very successful.

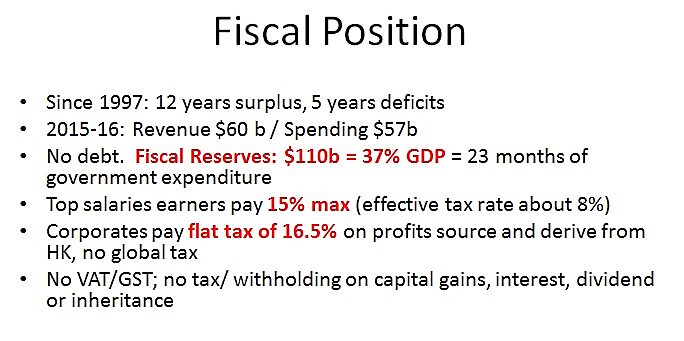

Our second speaker was Clement Leung, Hong Kong’s Commissioner to the United States. He talked about Article 107 and other rules from Hong Kong’s Basic Law (their constitution) that limit the temptation to over-tax and over-spend.

And if you want to see some of the positive results of these rules in Hong Kong, here’s some of what Commissioner Leung presented.

By the way, the burden of government spending in Hong Kong averages about 18 percent of economic output. That’s the most impressive result. And Commissioner Leung explained that there’s a commitment to keep the burden of spending below 20 percent of GDP.

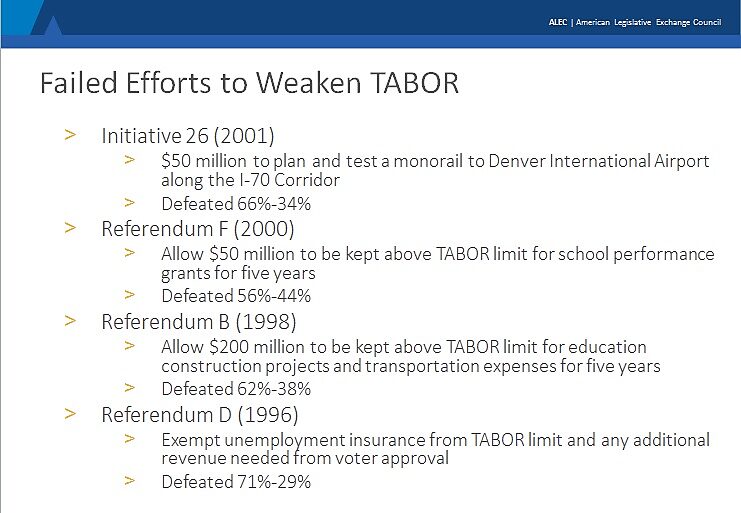

The final panelist was Jonathan Williams from the American Legislative Exchange Council, and he talked about Colorado’s Taxpayer Bill of Rights, popularly known as TABOR.

Jonathan talked about how the pro-spending lobbies keep attacking TABOR, and he mentioned that they narrowly succeeded in getting a five-year suspension of the law back in 2005. But Colorado voters generally understand they have a good policy.

The most recent attempt to enable more spending came in the form an increase in the state’s flat tax back in 2013 and voters rejected it by a stunning 66–34 margin (almost as impressive as the recent vote against tax hikes in Michigan) even though Jonathan said advocates outspent opponents by a 289–1 margin.

Here’s a slide from his presentation showing what happened during other attempts to enable more spending.

By the way, Jonathan also mentioned that Colorado’s voters are about to get a TABOR-mandated tax cut because taxes on marijuana are pushing revenues above the limit. Talk about a win-win situation!

To wrap up, one of the big lessons from all the presentations is that governments generally get in trouble because they can’t resist over-spending when the economy is doing well and generating lots of tax revenue.

I fully agree, and I’ve previously explained this is why Alberta got in fiscal trouble, and also why California suffers a boom-bust budgetary cycle.

The way you solve this problem is not with a balanced budget requirement (which often serves as the justification for tax hikes), but some sort of spending limitation rule.