One of the most remarkable developments in the world of fiscal policy is that even left-leaning international bureaucracies are beginning to embrace spending caps as the only effective and successful rule for fiscal policy.

The International Monetary Fund is infamous because senior officials relentlessly advocate for tax hikes,

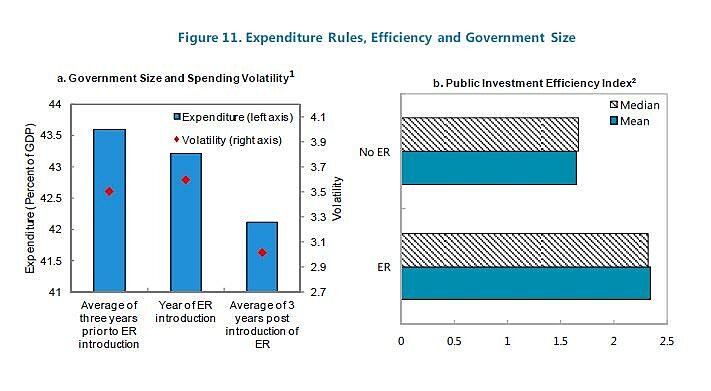

but the professional economists at the organization have concluded in two separate studies (see here and here) that expenditure limits produce good results.

Likewise, the political appointees at the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development generally push a pro-tax increase agenda, but professional economists at the Paris-based bureaucracy also have produced studies (see here and here) showing that spending caps are the only approach that leads to good results.

Heck, even the European Central Bank has jumped into the issue with a study that reaches the same conclusion.

This doesn’t mean balanced budget requirements are bad, by the way, but the evidence shows that they aren’t very effective since they allow lots of spending when the economy is expanding (and thus generating tax revenue). But when the economy goes into recession (causing a drop in tax revenue), politicians impose tax hikes in hopes of propping up their previous spending commitments.

With a spending cap, by contrast, fiscal policy is very stable. Politicians know from one year to the next that they can increase spending by some modest amount. They don’t like the fact that they can’t approve big spending increases in the years when the economy is expanding, but that’s offset by the fact that they don’t have to cut spending when there’s a recession and revenues are falling.

From the perspective of taxpayers and the economy, the benefit of a spending cap (assuming it is well designed so that it satisfies Mitchell’s Golden Rule) is that

annual budgetary increases are lower than the long-run average growth of the private sector.

And nations that have followed such a policy have achieved very good results. The burden of government spending shrinks as a share of economic output, which naturally also leads to less red ink relative to the size of the private economy.

But it’s difficult to maintain spending discipline for multi-year periods. In most cases, governments that adopt good policy eventually capitulate to pressure from interest groups and start allowing the budget to expand too quickly.

That’s why the ideal policy is to make a spending cap part of a nation’s constitution.

That’s what happened in Switzerland early last decade thanks to a voter referendum. And that’s what has been part of Hong Kong’s Basic Law since it was approved back in 1990.

And while many nations struggle with ever-growing government, both Switzerland and Hong Kong have enjoyed good outcomes and considerable fiscal stability.

Now a Latin American nation may enact a similar reform. Brazil, which is suffering a recession in part because of bad government policies, is trying to boost its economy with market-based reforms. Given my interests, I’m especially excited that it has taken the first step in a much-needed effort to impose a spending cap.

The Brazil Chamber of Deputies on Monday voted in favor of a constitutional amendment that would limit government spending to counteract the country’s alarming economic downturn. …The amendment proposal must pass two rounds of voting in the lower House and Senate. Should it be passed, the government would limit spending increases to the rate of inflation… Following approval, the amendment would take effect in 2017.

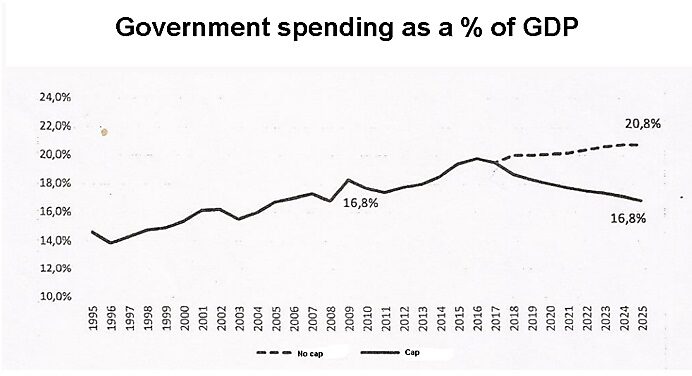

The specific reform in Brazil would limit spending so it doesn’t grow faster than inflation. And it would apply only to the central government, so the provinces would be unaffected.

Capping central government outlays would be a significant step in the right direction. The central government would consume 16.8 percent of economic output in 2025 with the cap, compared to 20.8 percent of GDP if fiscal policy is left on autopilot.

Of course, there’s no guarantee this reform will become part of the Constitution. It needs to be approved a second time by the Chamber of Deputies (akin to our House of Representatives) and then be approved twice by the Senate.

But the good news is that more than 71 percent of Deputies voted for the measure. And there’s every reason to expect a sufficient number of votes when it come up for a second vote.

Brazil’s Senate, however, may be more of a challenge. Especially since various interest groups are now mobilizing against the proposal.

Advocates of the reform should go over the heads of the interest groups and other pro-spending lobbies and educate the Brazilian people. They should make two arguments that hopefully will be appealing even to those who don’t understand economic policy.

First, a spending cap doesn’t require spending cuts in a downturn. Outlays can continue to grow according to the formula. This should be a compelling argument for Keynesians who think government spending somehow stimulates growth (and also may appease those who simply think it is “harsh” to reduce spending when the economy is in recession).

Second, by preventing big spending increases during the boom years, a spending cap is a self-imposed constraint to protect against “Goldfish Government,” which should be an effective argument for those who are familiar with the underlying fiscal and demographic trends that already have caused so much chaos and misery in nations such as Greece.

P.S. While I haven’t been a fan of Brazilian economic policy in past years, I actually defended that nation when Hillary Clinton applauded Brazil for being more statist than it actually is.

P.P.S. Being less statist than Hillary is not exactly something to brag about, so I will note that Brazil deserves credit for moving in the right direction on gun rights and also having some semi-honest left-wing politicians.