The H‑2A visa program exists to provide U.S. farmers with legal foreign workers when they cannot find U.S. workers as an alternative to illegal immigration and illegal employment. The government requires H‑2A employers provide —among other benefits—high wages, free housing, free transportation, and three meals or a kitchen. Despite these requirements, a lengthy NBC News report released this week details a story of horrific abuse of a group of H‑2A workers and concludes that “as the H‑2A program has expanded, it has left more guest workers vulnerable to abuse.”

Unfortunately, while highlighting important issues and one person’s dramatic criminal behavior, the report has several flaws and inaccuracies that incorrectly create the impression of widespread, systematic abuse of H‑2A workers. In general, nearly all H‑2A workers benefit greatly from working in the United States.

Problems with NBC’s reporting

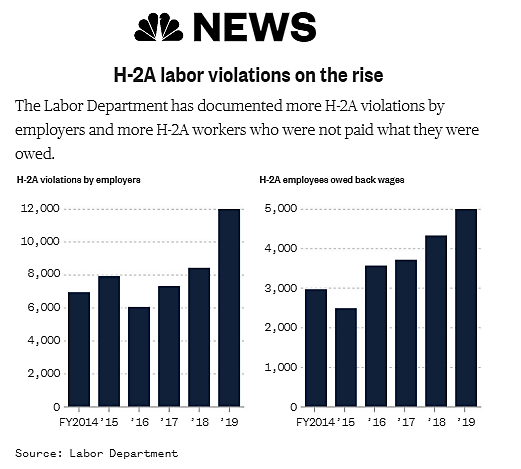

This post will criticize the use of certain data in this reporting, but I want to be clear at the outset that the narrative component of the story has journalistic merit that does illustrate real issues that can arise with the H‑2A program. However, the report grounds its narrative in a couple data points delivered at the top of the piece (along with the graphic) that are problematic:

Last year, the Labor Department closed 431 cases with confirmed H‑2A violations — a 150 percent increase since 2014; the agency found about 12,000 violations under the program, with nearly 5,000 H‑2A workers cheated out of their wages, according to federal data.

There are several issues with this presentation of data:

No recent upward trend in H‑2A violations: Despite the jump in violations last year, a fuller presentation of the data over both Obama and Trump’s terms shows, first, that a similar number of absolute violations were found in 2012 and 2013 (the year before NBC’s graph cuts off) and, second, that the number of violations per 1,000 H‑2A jobs is still 29 percent lower than the average year since 2000. The program has grown much faster than the number of violations. Figure 1 shows both the absolute numbers and the number of violations per 1,000 H‑2A jobs. Of course, the data could be missing violations that DOL never caught, but this would also have been true in 2012 and 2013, and the trends cut against the journalists’ narrative and should have been acknowledged.

Incorrect claim about backpay. The claim that “nearly 5,000 H‑2A workers cheated out of their wages” is simply incorrect. The Department of Labor (DOL) does report that nearly 5,000 workers received back wages from H‑2A investigations, but these workers include U.S. workers. Government regulations require that H‑2A farmers pay all their workers—both H‑2A workers and U.S. workers in “corresponding employment”—the Adverse Effect Wage Rate (AEWR) for the state (H‑2A’s inflated minimum wage) on top of the free housing, free transportation, etc. If the DOL audits an employer and finds that only H‑2A workers received the AEWR while U.S. workers received the market wage, it will cite the employer and require them to pay backpay to U.S. workers, even if the U.S. workers never asked or were promised the AEWR.

Matthews Sweet Potato Farm, for example, last year paid $56,193 in back wages to 113 employees because, as DOL states, “the employer gave H‑2A workers preferential treatment when they paid American workers less than … U.S. workers.” This fact is very important for the reader to know because it cuts against the theory that it’s always H‑2A foreign workers receiving lower pay than U.S. workers. The H‑2A program is often so generous—not just in theory but in practice—about pay for guest workers that it often penalizes employers for treating them better than Americans.

No recent upward trend in workers receiving backpay. NBC cuts off the available data, so the reader cannot see that in 2013, the number of (again, total) workers receiving backpay was similar to what it was last year. Moreover, since the program has expanded so dramatically in recent years, it simply isn’t reasonable to show the absolute number of workers receiving backpay without context. Figure 2 shows these trends as well. The number of workers receiving backpay per 1,000 H‑2A jobs was 57 percent lower than its peak in 2013 and 6 percent below the average for all years. Nothing unprecedented is happening with violations or backpay in the H‑2A program under President Trump.

No context about the significance of the infractions: NBC focuses on a horrific case of fraud and abuse but then lumps that case with all other infractions as if they are similar. They are not. The maximum available fine for a single H‑2A violation in 2019 was $115,624. The actual average fine amount per violation was just $237. Moreover, in about 29 percent of cases in 2019, DOL considered all of the infractions found so minor that it wasn’t worth a fine at all. Figure 3 actually shows a decline in the number of more serious infractions valued at more than $10,000 declined from 26 percent of cases to 7 percent from 2011 to 2019. H‑2A opponents sometimes use these facts to imply that DOL is so cozy with employers that it is unwilling to do anything about H‑2A violations. This is absurd and cuts against decades of hostility between the DOL and employers.

No context about the frequency of H‑2A employer violators. The vast majority of H‑2A employers aren’t violators. Figure 4 shows the number of H‑2A employers who were fined in recent years compared to the number of total H‑2A employers. With more than 6,000 employers, some people will violate the law, but it is by no means significant.

No context about the frequency of H‑2A trafficking: As I note in my report, the Department of Homeland Security granted T visa status (for human trafficking victims like those documented in the NBC report) to 39 H‑2A workers from 2009 to 2013, which represents 0.01 percent of H‑2A visas issued. Polaris, a group dedicated to combating human trafficking, received 327 complaints to its human trafficking hotline from H‑2A visa holders from 2015 to 2017—about 0.08 percent of visas issued. These are tragic cases, but as David Medina of Polaris told the Guardian, most H‑2A workers’ “biggest fear is to lose that visa.”

Little context about H‑2A’s value for foreign workers: Nearly all H‑2A workers try to return to the United States repeatedly because, whatever its flaws, it provides a better standard of living than their home countries. The annualized wage for H‑2A workers was almost $25,000 in 2019. Mexico’s minimum wage for farmworkers was just $4.64 per day, less than $1,200 per year. Even the highest paid agricultural workers in Mexico only earn $15 per day. “In Mexico, they pay very little,” one Tennessee H‑2A worker said. “You work all day and you earn what you earn here in an hour. It’s a big difference.”

But it’s not just the wages. H‑2A employment is legal employment with legal status. This is huge benefit to workers who may otherwise cross illegally in dangerous conditions. As one former-illegal, but now H‑2A worker explained, “I don’t have to risk my life anymore to support my family. And when I am here, I do not have to live in hiding.” This partly explains, as seen in Figure 5, why the rise in H‑2A and H‑2B visas for Mexicans has corresponded with a major decrease in illegal immigration from Mexico. H‑2A visas are usually better than the alternatives for nearly all H‑2A workers, whether staying at home or crossing illegally.

Inaccurate report of a significant decline in investigative resources: NBC states that staff at the Wage and Hour Division (WHD), the Department of Labor’s agency responsible for H‑2A enforcement, “has fallen by 19 percent since 2016, according to federal records.” NBC doesn’t link to the federal records it references, but it appears that this statement came from comparing the proposed number of full-time equivalent workers for FY 2016 to the total number of actual or proposed workers in FY 2020. Whatever the case, the 19 percent reduction in WHD staff did not occur. In FY 2020, the agency had 1,382 full-time equivalent employees (excluding the H‑1B fraud staff who are separately funded by employer fees). This compares to 1,359 in FY 2016. Including the H‑1B staff doesn’t make the claim correct or substantially change the trends. Figure 6 shows the full trend for WHD staff.

Little context about H‑2A’s complexity: NBC notes that farmers say that the program is complex, but this fact is only affirmed in passing and only as an explanation for why farmers are using labor contractors (which, in the highlighted case, abused the workers in NBC’s story), not as an explanation for the violations themselves. The Government Accountability Office has found that the “complexity of the H‑2A program poses a challenge for some employers” because it “involves multiple agencies and numerous detailed program rules that sometimes conflict with other laws.” In 2014, the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) ombudsman characterized it simply as “highly regulated.” My own report details a noncomprehensive list of 209 H‑2A rules that apply to farmers and workers. This flow chart from my report gives a small glimpse into the regulatory hurdles for H‑2A employers.

It’s inevitable as new employers join a very complicated program that some violations will occur. For example, violations of the “corresponding employment” rule—mentioned above—are common because the belief naturally arises that only Americans recruited by the employer as part of the H‑2A process are subject to it. This isn’t so. Moreover, it’s exceptionally difficult outside of that process to determine who a “corresponding” worker is, if workers perform different tasks at different times of the year.

Important insights from the NBC story

Despite the shortcomings of its presentation of the data and facts about the program, the NBC narrative does contain some important insights about reforming the H‑2A program. An H‑2A labor contractor—an individual named Manuel Sanchez—with a contract with Premium Pineneedles in Georgia recruited Mexicans to bale pine straw for garden mulch. He promised them all the normal H‑2A benefits but illegally charged them a $1,600 to join, nearly the first month’s expected pay. Once they reached Georgia, Sanchez dumped them without gloves or equipment in a forest to pick up pine needles with their bare hands and forced them to live in abandoned and dilapidated housing without enough food.

Workers want a legal alternative to illegal immigration: NBC states:

Six years earlier, Reyes had crossed the U.S.-Mexico border on foot, without papers. He was caught in Texas, then deported after two weeks in detention. This time would be different, Reyes told himself: “I want to do things the right way — legally.”

This accords with the experience of many other guest workers who chose the H‑2A or H‑2B guest worker programs because they were better alternatives to illegal residence. Without the H‑2A program, many more workers would continue to attempt to cross the border illegally, placing them in a worse position with their employers and the law. This insight cuts strongly against curtailing the H‑2A program.

Make the program less complex: NBC reports:

The program’s growth has spawned a cottage industry of visa agents and growers associations to help farmers navigate the complex application process. But increasingly, farmers are turning to farm labor contractors like [the abusive] Sanchez to supply workers.… farmers are outsourcing the time-consuming job of hiring, transporting, housing and managing H‑2A workers. Labor contractors can also shield farmers from liability, curtailing their legal responsibility for the workers picking their crops should something go wrong.

These statements imply that farmers would be much more likely to hire workers directly and manage the workers themselves if the program was less complex. This is sensible. Simplifying the H‑2A program would benefit both workers and employers. This insight undercuts the argument for adding even more regulations to the program.

Inform workers of their rights: NBC explains that it took a local pastor to explain to them their rights:

The following night, the workers heard a knock on their door. The men scattered. Some hid inside the house, Luna recalled, fearing that immigration agents had come to deport them, as Sanchez kept threatening would happen, even though they’d done nothing wrong. … [The pastor] Marcela De Leon was overwhelmed. “This is abuse,” she said, telling the men to speak to a lawyer. “You have to report it.”

Every H‑2A worker first has a visa interview at a U.S. embassy or consulate. Consular officers at the end of those interviews should be informing workers of their rights. Every interview should conclude with the promised job conditions and where to go if those conditions are not met. No H‑2A worker should believe that reporting human trafficking and fraud should result in deportation. They should understand the availability of T visas for trafficking victims, which the workers ultimately obtained.

Allow workers to leave their jobs without fear of losing status: NBC reports that for the workers:

their greatest fear — more than being mistreated — was never being able to come work in America again. What would all that suffering have been for? “All that time in vain,” as one of the men later put it.

For U.S. workers, leaving a job is never easy, but there’s no risk that you will never be able to work in America again. Foreign workers need the same assurance. If workers can leave their jobs to find new ones, they can assert their rights more vigorously and blunt the fear of losing financially. Unfortunately, the H‑2A program makes this exceptionally difficult. H‑2A status automatically expires 30 days after the end of the first job. The regulation is not at all clear that this 30-day period applies to workers who “abscond” from their first job, but it should be universal. Moreover, 30 days is not enough assurance for workers. The H‑2A program should guarantee a minimum of a year’s status with renewals possible with proof that the worker is continuing to find jobs.

As importantly, all the regulatory red tape to hire a foreign worker—which takes about 90 days to complete—makes it almost impossible to quickly connect to a new employer that isn’t already interested in H‑2A workers. The government should allow farmers to hire H‑2A workers already in the United States on the same terms as their U.S. workers. The statutory requirements only apply to employers seeking to “import” a foreign worker, not to those already present in the country. Moreover, under the statute, employers should be required to hire available H‑2A workers first because the statute requires them to seek any available worker (without specifying U.S. worker) in the United States.

More visas will reduce abuse: NBC reports:

Sanchez, whom he met through a friend, told [the worker] that it would cost $1,600 for the visa, transportation and a “special” passport that turned out not to exist.

It is almost impossible to stop these deals if workers fail to report them—another reason that workers should receive detailed instructions about their rights at the visa interview. In a free market, workers would enter the country and find jobs in the same manner as U.S. workers cross states, which would deny unscrupulous recruiters their power. Even without that ideal, it remains true that the more visas are available, the greater the bargaining power of the workers become. If visas are easy to come by, then workers will be less willing to pay or not be willing to pay as much.

Conclusion

I have asked NBC to correct its report with respect to the claim that 5,000 H‑2A workers were cheated out of their wages in 2019, since it is incorrect, but so far no correction has come. It would have been nice if they had quoted at least one worker supportive of the program (there are hundreds of thousands) or quoted a proponent of the program that wasn’t an employer (which may have caught some of the issues above). Another bit of missing context is the fact that entirely aside from the H‑2A program, some employers in every industry sometimes lie and defraud U.S. workers too. They fail to pay them what they are owed. The only way to reach zero abuse is to stop all hiring, which is obviously not a realistic proposal. Instead, we need to empower workers to understand and stand up for their rights.