A couple of recent New York Times articles discuss pregnancy discrimination in the workplace. In its most recent spread, the Times outlines a variety of stories of expectant mothers losing jobs or job responsibilities and cites the growing number of pregnancy-related Equal Employment Opportunity complaints to imply rates of pregnancy discrimination may be increasing.[1]

As a solution, the article’s authors propose pregnant women would be better off with additional government protection, perhaps similar to the protection afforded to Americans with disabilities. The Times should be careful what it wishes for.

While arguing for added protections for pregnant women, the Times forgets to mention that rights to accommodation for people with disabilities didn’t work out as planned. One study finds the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 reduced “employment of disabled men of all working ages and disabled women under age 40.”

Other evidence finds the ADA reduced employment rates for men with disabilities by 7.2 percentage points and was “associated with lower relative earnings” and “slightly lower labor force participation rates” for people with disabilities.

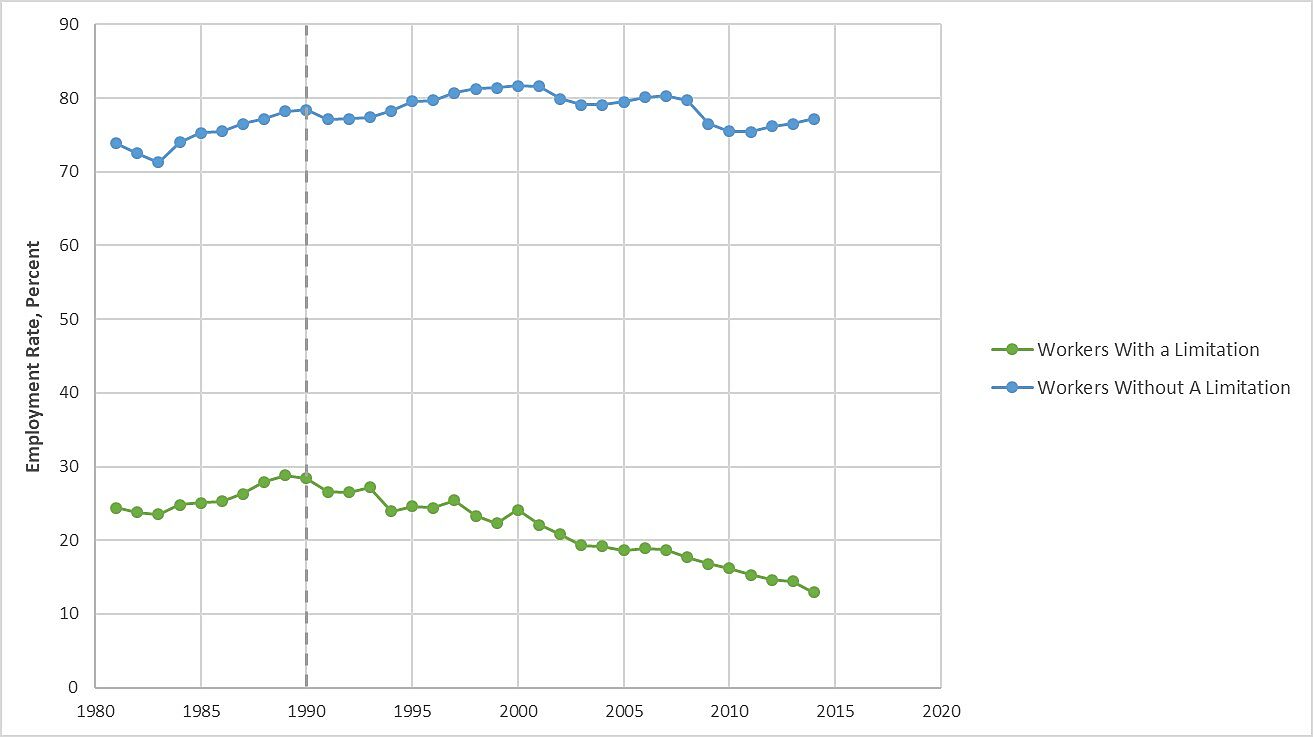

Indeed, when ADA took effect in 1990, 28.4 percent of people with disabilities were employed (compared with 78.4 percent of non-disabled persons). In 2014, the employment rate for people with disabilities had fallen to 12.9, or less than half of the 1990 figure. The employment rate didn’t changed much for non-disabled persons, so the employment gap between disabled and non-disabled widened considerably during this period.

Figure 1: Employment Rate Through Time for Persons with and Without Disabilities, Ages 21–64

The government was trying to help people with disabilities, so why did ADA hurt their employment prospects? A 2010 study examining the ADA 20 years after its passage concludes

“The unclear expectations on what constitutes appropriate accommodations for people with disabilities is likely having a chilling effect on the employment prospects of the disabled population. Fears of costly litigation and administrative grievances are driving some employers to be suspect, if not downright hostile, to hiring workers with a disability. Reflecting an all too common irony in social policy, the ADA might be having the exact opposite effect of the intent of the legislation.”

divAccording to the Times, pregnant women should have the same accommodation rights. But if pregnant women knew about the impact of the ADA on disabled population, fewer might be interested in this form of government “protection.”

[1] Note that these figures don’t provide evidence of that per se.