Prager University (PragerU), founded by radio talk-show host Dennis Prager and Allen Estrin, is a non-profit that makes short videos on political, economic, cultural, and philosophical topics from a conservative perspective. Last month, PragerU released a video called “A Nation of Immigration” narrated by Michelle Malkin, an individual most famously known for her defense of the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. The video is poorly framed, rife with errors and half-truths, leaves out a lot of relevant information, and comes to an anti-legal immigration conclusion that is unsupported by the evidence presented in the rest of the video. Below are quotes and claims from the video followed by my responses.

The United States still maintains the most generous [immigration] policies in the world. Generous to a fault …

There are two things wrong with the statement. The first is framing around the word “generous” and the second is the claim that the U.S. has the freest immigration policy in the world.

Using the word “generous” implies that allowing legal immigration is an act of charity by Americans and that we incur a net-cost from such openness. On the contrary, the economic evidence is clear that Americans benefit considerably from immigration via higher wages, lower government deficits, more innovation, their greater entrepreneurship, housing prices, and higher returns to capital.

Most immigrants come here for economic reasons. In what sense is it generous or charitable on the part of Americans to allow an immigrant to come here voluntarily and to work for an American employer? Not only do both the employer and the immigrant gain; the consumers, investors, and economy do as well.

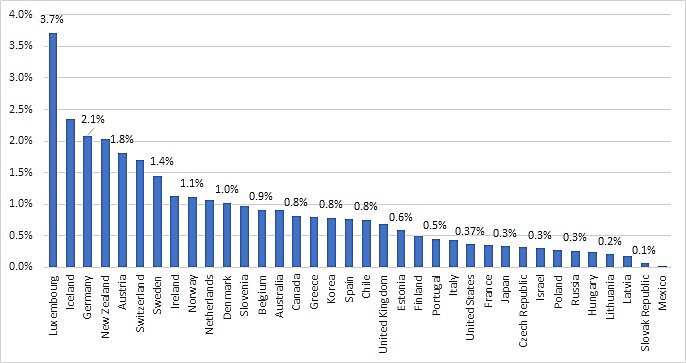

Second, the United States does not allow more legal immigrants to enter annually in comparison to other countries. When controlling for the population size of the destination country (excluding Turkey), the annual flow of immigrants to the United States is the 25th most open among the OECD countries in 2016 (Figure 1). Unlike other countries in the list, the OECD records the number of non-permanent migrants who entered the United States in 2016. Adding together the permanent immigrants and non-permanent migrants for the United States only and then comparing that new number to the permanent immigrant inflows in other OECD countries, which I am only doing to give Malkin the benefit of the doubt, turns the United States into the 20th most “generous” OECD country.

Malkin probably meant that the United States lets in a greater absolute number of immigrants per year than any other country in the world – which is true. But that’s not a meaningful statistic unless we control for the resident population of every country. Analyzing cross-country comparisons in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) makes this point well. According to the World Bank, the 2017 GDP for the United States in current dollars is $19.391 trillion and China’s is $12.238 trillion. By that measure, the United States is only 58 percent richer than China. However, that is deceptive because the population of China is about 4.3 times as great as the United States. Thus, the more meaningful GDP comparison between the two countries controls for population – a measure called GDP per capita. A cross-country measure of GDP per capita shows that Americans are individually 674 percent richer than individual Chinese. (There are other important variables for cross-country comparisons in GDP per capita, such a Purchasing Power Parity, but they aren’t relevant to the point here). In the same way that we must adjust for the population when comparing GDP between China and the United States, we must also control for population size when comparing the relative openness of immigration policies across the world.

Another relevant comparison to evaluate our country’s openness to immigration is to America’s past when the United States had a much more open immigration system. The number of immigrants who received green cards in 2016 was 1,183,505, below the 1,218,480 who arrived in 1914 when the United States was a much smaller country (I picked 1914 because that was the last year before World War I seriously limited European emigration). According to research by my colleague David Bier, the number of immigrants receiving green cards today is low compared to most of American history. The number of immigrants who received green cards in 2016 was equal to about one-third of one percent of the U.S. population – below the average annual rate of 0.45 percent from 1820 to today. In 19 years, mostly in the mid-late 19th and early 20th centuries, the annual number of green cards issued was equal to at least 1 percent of the U.S. population. Through comparison to America’s past and controlling for the number of residents over time by the time dimension itself, the current number of immigrants receiving green cards is relatively small.

Figure 1

Annual Permanent Immigrant Inflows as a Percent of the Destination Country’s Population, 2016

Sources: OECD and World Bank.

… the overwhelming numbers [of immigrants] have stymied our ability to assimilate the huddled masses.

There’s never been a greater quantity of high-quality quantitative research that shows that immigrants are assimilating and becoming Americans at a rapid clip. The first piece of such research is the National Academy of Science’s (NAS) September 2015 book titled The Integration of Immigrants into American Society. This 520-page book is a thorough summation of the relevant academic literature on immigrant assimilation. The bottom line of the book: Assimilation is never perfect and always takes time, but it’s going very well in the United States.

The second piece of research is a July 2015 book entitled Indicators of Immigrant Integration 2015 that analyses immigrant and second-generation integration using 27 measurable indicators across the OECD and EU. This report finds problems with immigrant assimilation in Europe, especially for those from outside of the European Union, but the findings for the United States are positive. In comparison to Europe and the rest of the OECD, immigrants in the United States are assimilating very well.

The third work by University of Washington economist Jacob Vigdor offers a historical perspective. He compares modern immigrant civic and cultural assimilation to the level of immigrant assimilation in the early 20th century (an earlier draft of his book chapter is here while the published version is available in this collection). For those of us who think early 20th century immigrants from Italy, Russia, Poland, Eastern Europe, and elsewhere assimilated successfully, Vigdor’s conclusion is reassuring:

“While there are reasons to think of contemporary migration from Spanish-speaking nations as distinct from earlier waves of immigration, evidence does not support the notion that this wave of migration poses a true threat to the institutions that withstood those earlier waves. Basic indicators of assimilation, from naturalization to English ability, are if anything stronger now than they were a century ago [emphasis added].”

50 million residents of America are foreign-born. In fact, today the United States has more immigrants as a percentage of its total population than at any time since 1890.

According to the 2016 American Community Survey (ACS), there were 43.7 million foreign-born residents of the United States in 2016 (Advanced Search, Table S0501, 1‑year sample). Since the publication of PragerU’s video, the government released the 2017 ACS which estimates that there were 44,525,855 immigrants living in the United States last year. The immigration restrictionist Center for Immigration Studies reported the same numbers. This means that the foreign-born resident population was 13.5 percent of the U.S. population in 2016, below the 14.8 percent record set in 1890. Malkin was correct in highlighting 1890 because that is when the foreign-born percentage of the population peaked. However, the foreign-born percent was higher, relative to today, in 1900 and 1910 too. Perplexingly, the source that Malkin provides states that there were over 43.2 million immigrants in 2015, not the 50 million that she claims. PragerU should correct this factual error.

Oddly enough, Malkin never actually mentions the percentage of the population that is foreign-born. A new working paper by economists Alberto Alesina, Armando Miano, and Stefanie Stantcheva shows the results of surveys across six countries to see how natives view immigrants. They found that Americans, as well as natives from other countries, systematically overestimate the percentage of the population who are legal immigrants (they specifically asked about legal immigrants and made it clear that they were not asking about illegal immigrants). The average native-born American’s perceived share of legal immigrants was 36.1 percent of the population, almost 4 times the actual 10 percent figure (the ACS figure above includes illegal immigrants). Importantly, people who are more likely to be opposed to liberal immigration policies think the percentages are even higher.

One of the purposes of PragerU videos is to inform viewers about facts that are ignored by liberals. The research by Alesina, Miano, and Stantcheva illustrates how many Americans are ill-informed regarding the percent of the population that is foreign-born. This video was a wonderful opportunity to state the actual percentage of the population that is foreign-born, something that would have been a great service. It’s a shame Malkin neglected to do so.

Chain migration allows immigrants to sponsor not only their immediate family – parents, spouses, and children under age 21, but much of their extended family once they gain citizenship … Princeton University researchers, using the most recently available data, found that immigrants sponsored an average of 3.45 additional relatives each. So, the one million immigrants granted permanent residence each year potentially adds, over time, another three and a half million.

There are five important points that Malkin neglects to mention that are critical to put this statement in context.

First, the annual cap on the number of immigrants who are not the spouses, minor children, or parents of U.S. citizens is 226,000 per year. This is hardly a flood but it is true that many of these immigrants eventually sponsor other family members who are either immediate relatives, siblings, and/or adult children.

Second, the wait time to sponsor an immigrant through the family-based green card system is long and varies by the immigrant’s country of origin. The government issues a “priority date” for people who want to apply for green cards. When that date comes up, then the applicants can apply. According to the U.S. Department of State, the government is accepting green card applications for certain family-based green cards (F‑1 through F‑4) for those who have a priority date before the dates below (Table 1). The F‑2A visa is for the spouses and minor children of those who already have green cards and is effectively capped at 87,934 per year. Those who had a priority date for the F‑2A before December 1, 2017, can now apply for a green card. This is unlike other family-based green card categories. The wait time is over 20 years for Mexicans and Filipinos on the F3 and F4 green cards and for Mexicans on the F1. These long waits mean that about 4 million people were waiting to apply for a family-based green card at the end of 2017.

Table 1

Dates for Filing Family-Sponsored Visa Applications Based on Priority Dates

| Family- Sponsored |

Other Countries | China | India | Mexico | Philippines |

| F1 | 08MAR12 | 08MAR12 | 08MAR12 | 01SEP98 | 15FEB08 |

| F2A | 01DEC17 | 01DEC17 | 01DEC17 | 01DEC17 | 01DEC17 |

| F2B | 22MAR14 | 22MAR14 | 22MAR14 | 08JUN97 | 15DEC07 |

| F3 | 22SEP06 | 22SEP06 | 22SEP06 | 08OCT98 | 01AUG95 |

| F4 | 01MAY05 | 01MAY05 | 01JAN05 | 01JUN98 | 01DEC95 |

Source: U.S. Department of State.

Third, the long wait times in Table 1 mean that Americans can only sponsor some of their family members. The long waits discourage many from applying and some actually die while waiting. Malkin mentioned a Princeton study that found that the average immigrant who arrived from 1996–2000 sponsored 3.46 family members. The author of that study went on to say that that was largely driven by high skilled employment-based immigrants sponsoring their families because these high-skilled immigrants are more likely to be naturalized. It was not driven not by family-based immigrants who sponsored additional family members.

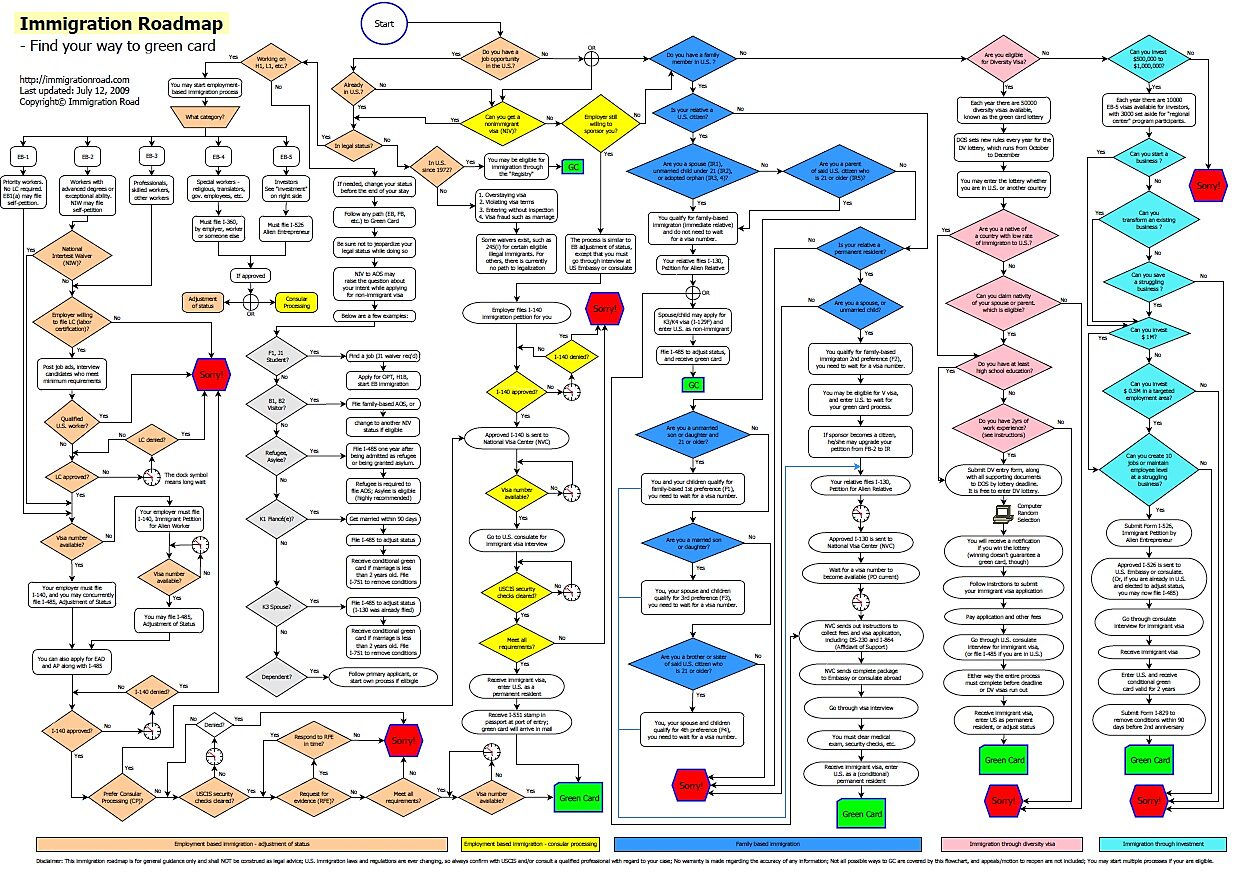

Fourth, the legal immigration system is extremely complex and restrictive. Family members of American citizens or immigrants are not just waved in. Rutgers law professor Elizabeth Hull wrote, “With only a small degree of hyperbole, the immigration laws have been termed ‘second only to the Internal Revenue Code in complexity.’ A lawyer is often the only person who could thread the labyrinth.” A judge wrote that “This case vividly illustrates the labyrinthine character of modern immigration law‑a maze of hyper-technical statutes and regulations that engender waste, delay, and confusion for the Government and petitioners alike.”

Figure 2 is a simplified legal map of the green card system. People watching the PragerU video could get the impression that it is easy to immigrate to the United States but that is a myth rooted in mainstream American perceptions of our history, not an accurate recounting of current law and policy.

Figure 2

Legal Immigration System

Source: Immigration Road.

Fifth, the United States has the seventh most open family-based immigration system when compared to OECD countries. According to my own estimates, New Zealand, Sweden, Ireland, Australia, Norway, and Canada all allowed more family-based immigrants in 2013 than the United States did, statistically discussed as a percentage of their respective populations. Those countries allowed in fewer types of family relations but, because they allowed in more legal immigrants overall, the relative percentage of family-based immigrants was also higher.

Sixth, the legal family-based immigration system (also known as chain migration) was created by Congress in 1921 when they placed the first numerical caps on European immigrants that favored Northern and Western Europeans based largely on long-discredited eugenics theories. When the immigration system was slightly liberalized after the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965 went into effect, immigration restrictionists were the ones who argued for expanding family-based immigration. Tom Gjelten provides substantial evidence that immigration restrictionists in the 1960s favored expanding chain migration because most immigrants at the time were Europeans. Thus, the restrictionists thought that a new immigration system based on family reunification would mostly allow European immigrants to sponsor their family members and basically recreate the caps that favored Northern and Western Europeans at the detriment of other populations. These immigration restrictionists seriously miscalculated.

In addition, an estimated 100,000 refugees and asylum-seekers–people who claim to be fleeing political or personal strife abroad–enter the country annually.

Malkin is double-counting. Those 100,000 refugees and asylum-seekers that she mentions eventually get green cards, which she stated above amount to about 1 million a year. Thus, these 100,000 refugees and asylum-seekers are not “in addition” to the one million who earn permanent residency a year as they are eventually counted as permanent residents. Over the last several years, about half of the green cards issued were to those who came directly from abroad and the other half went to immigrants already here on another visa – a process termed “adjustment of status.”

Furthermore, refugees and asylum-seekers have to do more than merely claim that they are “fleeing political or personal strife abroad,” they must show a well-founded fear of persecution in the future or that they have suffered from past persecution “on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.” Previous administrations have considered things like abuse or persistent gang violence that their home-country governments are incapable or unwilling to control as factors that could help an applicant obtain asylum. The refugee process occurs overseas and is arduous. Essentially, the U.S. government selects the refugees after having been initially screened by the United Nations. The other category, asylum-seekers, apply at U.S. ports of entry or inside of the country for humanitarian protection and must make their case in front of an immigration judge. Some asylum-seekers and refugees fraudulently claim that they have been persecuted but the system relies on more than just the statements of asylum-seekers.

In that same time frame [2008–2017], nearly half a million more people came to America through the diversity visa lottery – a program designed to admit people from ‘underrepresented’ countries. Diversity visa applicants don’t need a high school education, job skills – or pretty much anything.

An immigrant who applies for a Diversity visa must have a high school education, its equivalent, or two years of qualifying work experience as defined under provisions of U.S. law. It is simply inaccurate to state that they “don’t need a high school education, job skills, – or pretty much anything.” This is another factual error that PragerU should correct.

The number of illegal aliens in the country is usually given as 11 million, but have you noticed that number never seems to change? Common sense suggests it’s higher – much higher.

A recent paper published in the journal PLoS ONE claims that the actual number of illegal immigrants in the United States is likely between 16.2 and 29.5 million. Their finding is dubious for several reasons as explained by immigration researchers on both sides of this issue. Millions of additional illegal immigrants would have lots of births that are not currently recorded, fill the public schools with additional children who are not currently there, and would show up in surveys of employment and the workforce. Either these extra illegal immigrants have zero children and do not work, or they are simply not here.

But, let’s assume for the moment that Malkin’s “common sense” theory turns out to be true and there really are millions more illegal immigrants than demographers estimate. That would mean that illegal immigrants are far less likely to commit crimes than natives, have an even smaller effect on the wages of Americans, and are assimilating at a rapid pace. I don’t believe that Malkin intends to make this point but, if she’s correct, then she’s helped prove that illegal immigrants are among the safest people in America and are assimilating rapidly.

And though illegal aliens themselves don’t qualify for welfare, they receive free health care in our clinics and hospitals, and through their American-born children they can expect to receive all manner of benefits – cash aid, food stamps, and housing vouchers. Their children are entitled to a free education in public schools.

Malkin is correct that some illegal immigrants and their children do receive some welfare benefits but much less so than natives. Still, welfare is a problem and I’ve co-authored several pieces on how to build a wall around the welfare state instead of around the country. If welfare is a real concern, it is a lot easier to reform welfare than it is to tinker with the U.S. population through immigration controls in an age of low-cost transportation. I like to quip that immigration restrictionists use the welfare system to argue against immigration while real free-marketeers use immigration to argue against welfare.

Building a high-tech border barrier would certainly help stem this flow. Ending chain migration is another obvious remedy.

Malkin’s statement here conflates illegal and legal immigration. A border wall could only potentially hinder the flow of illegal immigrants into the United States but “ending chain migration” would cut legal immigration. Although Malkin isn’t specific in her video, her suggestion could cut the number of green cards issued annually by 20 percent to 68 percent (and potentially more depending on how it is counted).

Many conservatives rightly complain about pro-immigration advocates unfairly lumping in legal and illegal immigrants – so why is Malkin unfairly lumping policies to stop illegal immigration in with those to cut legal immigration without making an obvious distinction between the two? Just to be clear, family-based immigrants who arrive through the chain migration system are legal immigrants.

E‑Verify, the national database that allows employers to check workers’ immigration status, is also essential.

E‑Verify is not a database. It is an electronic eligibility for employment verification system run by the federal government that is supposed to check the identity information of new hires against government databases to deny employment to those legally ineligible to work. The intent of E‑Verify is to exclude illegal immigrant workers from the workforce to dis-incentivize them from coming in the first place.

Many immigration restrictionists sing E‑Verify’s praises but they rarely address its deep and persistent problems. Even worse, they never acknowledge that E‑Verify is ineffective. Barely more than half of the new hires in states where E‑Verify is mandated are actually run through it, E‑Verify erroneously approves about 54 percent of illegal workers for legal employment, E‑Verify doesn’t affect the wages of illegal immigrants much, and there are a host of other problems. Additionally, Arizona’s mandate of E‑Verify in 2008 may have increased crime there, and a nationwide mandate of E‑Verify will likely increase identity theft. Even worse, E‑Verify’s supporters have stoked high expectations for the program that will never be met. The best thing about E‑Verify is that it does not work very well and can never work well as currently designed. The worst thing about E‑Verify is how Congress will react if, after it mandates the program for all new hires, they find out that it does not work and then they create a more intrusive government identity system.

But all solutions will ultimately fail unless we get control of the numbers and enforce our laws consistently.

Malkin is arguing for enforcing immigration laws more consistently and changing those laws to cut legal immigration. Her rhetorical conflation of these two points is misleading and does a disservice to her audience who would probably like to distinguish legal immigration from illegal immigration.

Also, cutting the number of legal immigrants will make it harder to enforce immigration laws. Immigrants overwhelmingly come to the United States for economic opportunity. If they can’t come legally, then some percentage of them will come illegally. Creating a legal way for them to come or, at a minimum, not cutting those few legal avenues that do exist is essential to consistently enforcing our laws.

In the 1950s, the U.S. government decreased the number of illegal Mexican immigrants by about 90 percent by combining a massive expansion in guest worker visas through the Bracero program with more enforcement. At the time, a Border Patrol official warned that if the Bracero program was ever “repealed or a restriction placed on the number of braceros allowed to enter the United States, we can look forward to a large increase in the number of illegal alien entrants into the United States.” That is exactly what happened when Congress canceled the Bracero program in 1964.

It’s Sovereignty 101: This is our home and we have not only the right, but the responsibility, to determine who comes in, how many come in, and what qualities and qualifications they bring.

There are few scholars who doubt that the U.S. government has the legitimate constitutional power to regulate immigration, but the specific immigration policy that Congress chooses has little to do with national sovereignty as foreign governments do not have a hand in it.

The standard Weberian definition of a government is an institution that has a monopoly (or near monopoly) on the legitimate use of violence within a certain geographical area. The way it achieves this monopoly is by keeping out other competing sovereigns (a.k.a. governments, countries, nations, etc.) that seek to become that monopoly of legitimate coercion. The two main ways our government does that is by keeping the militaries of other sovereigns out of the United States and by stopping insurgents or potential insurgents from seizing power through violence and supplanting the U.S. government.

U.S. immigration laws are not primarily designed or intended to keep out foreign armies, spies, or insurgents. The main effect of our immigration laws is to prevent willing foreign workers from selling their labor to willing American purchasers. Such economic controls do not aid in the maintenance of national sovereignty and relaxing or removing them would not infringe upon the government’s national sovereignty any more than a policy of unilateral free trade would. There are individual exceptions to this like an immigrant who is a terrorist or an agent of a foreign government, but those are rare exceptions even for illegal immigrants.

Less-than-perfect enforcement of our immigration laws does not diminish national sovereignty because those coming are not agents of foreign governments or other groups trying to conquer the United States and diminish our government’s monopoly on the use of violence. It would be an odd standard to argue that any less-than-perfect enforcement of American laws diminishes sovereignty, even if those laws are largely intended to regulate Americans’ interaction with foreigners who are not a national security threat. Less-than-perfect enforcement is evidence that Congress is either uninterested and/or incapable of doing so better, not that national sovereignty is somehow infringed.

It’s not hateful to protect our borders. It’s not hateful to protect our citizens.

This depends on how the government conducts border security relative to the seriousness of the threat. It’s easy to argue that the U.S. government’s policy of separating the young children of asylum seekers from their parents is an action far crueler than what action is required to deal with the manageable threats of crime and terrorism. Previous administrations have cruelly blocked immigrants on dubious grounds that one should call hateful. Proponents of those laws certainly thought they protected American citizens. Almost all of us would support very cruel policies to defend the United States from great and serious threats but having a cruel policy for no good reason isn’t reasonable.

It’s not hateful to protect our values.

One of our core American values is an openness to immigration, as Malkin acknowledged at the beginning of this video. Although our government has not always followed that principle well, it is part of our exceptional national character. Progressive and nationalist politicians violated those values when they slowly closed the border in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Today, many self-described conservatives are the biggest proponents for rejecting Western Civilization’s ancient pro-immigration history, a history that is especially relevant in the United States.

Lady Liberty may be shedding tears – not because we’ve stopped welcoming immigrants, but because our ill-conceived immigration policies are threatening the American Dream.

This conclusion does not follow from the arguments in Malkin’s video. Americans are getting richer, achieving more, and leading the world in numerous endeavors while immigration is increasing. Although Malkin does not define what the “American Dream” is, it’s certainly not diminishing. A great measure of the vitality of the American Dream is the tens of millions of foreigners who want to immigrate here and become Americans. We should all be proud that immigrants from around the world want to come here and join our country. Our government should allow them to do so more easily and cheaply because it is in our best interests to and consistent with our values.