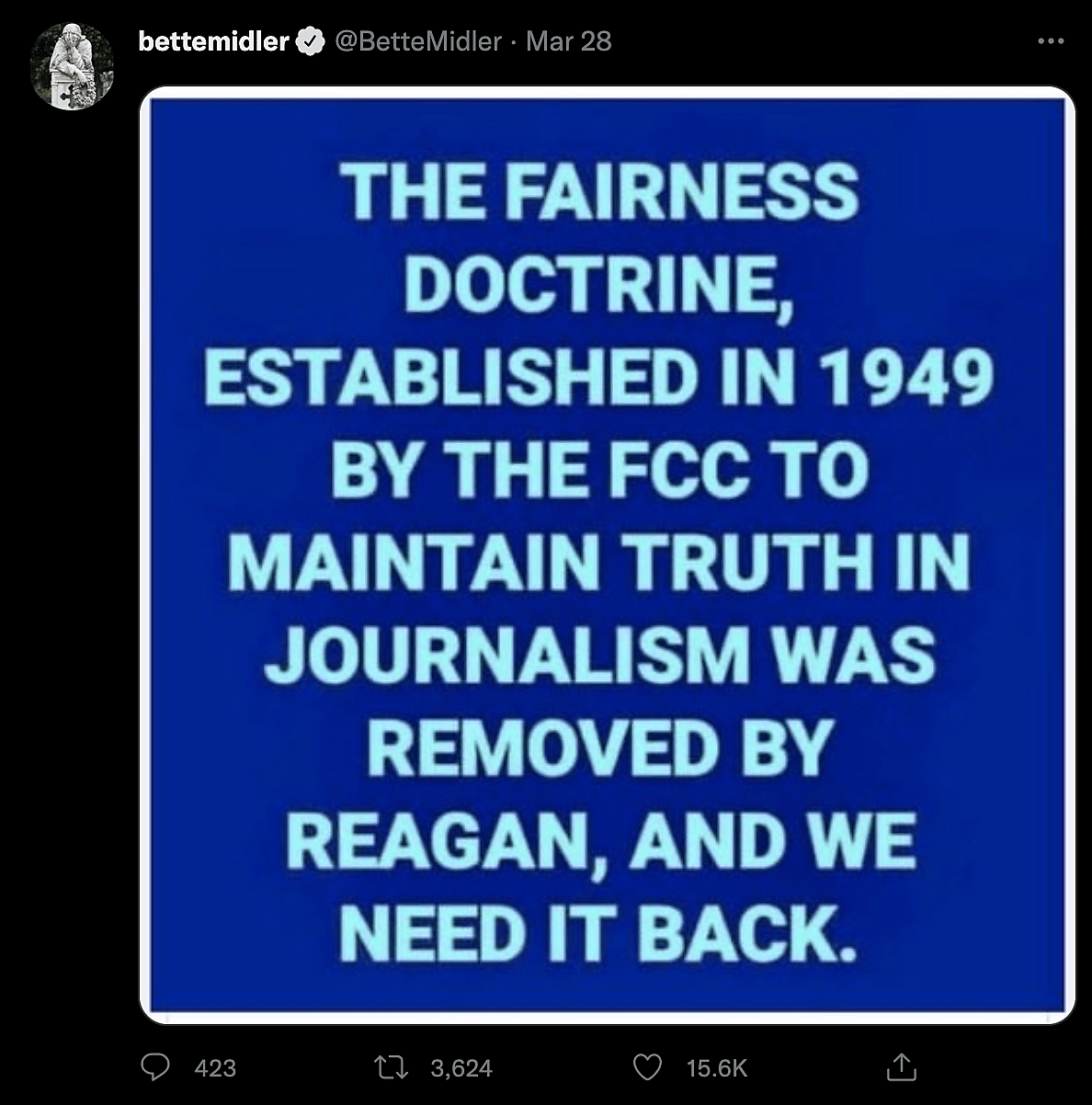

Earlier this week, actress and comedian Bette Midler tweeted the following image calling for the reintroduction of the Fairness Doctrine to her two million followers.

As I’ve written elsewhere, the Fairness Doctrine was responsible for one of the most successful episodes of government censorship in US history. The Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon administrations each weaponized the rules to punish their political opponents, especially those in conservative radio broadcasting. However, the image Midler shared is particularly notable in both the ways that it is incorrect and what that says about growing public openness to government regulation of media.

I have promised a truth and three lies, so let’s start with the truth, that the Fairness Doctrine was established by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). It was an attempt by the Commission to solve a problem of its own creation. It wanted to remove the chilling effect created by prior regulations, encourage broadcasters to air content about “controversial issues of public importance,” and to do so without unbalanced editorializing of the personal views of the broadcaster.

This leads us to the first of the lies, or at least misdirections. The FCC had expressed a desire for “fairness” and “balanced” coverage in 1949, but the Fairness Doctrine (FD) would not be codified until 1959. Furthermore, enforcement of the FD would wait until 1963, when President Kennedy told his newly appointed FCC Chairman “that stations be kept fair,” at least when it came to coverage of his legislative agenda. Thus, the Fairness Doctrine regime was not as old as Midler’s tweet would have it.

The second lie is to blame only President Reagan for the FD’s removal. While it is true that Reagan’s FCC repealed the FD and Reagan vetoed a congressional effort to reinstate the rule in 1987, the doctrine had been mostly dead letter since the late 1970s. The death of the Fairness Doctrine began with President Jimmy Carter, the underrated great deregulator of everything from airline routes to craft beer and mass media. Thus, the “high” period of Fairness Doctrine enforcement lasted only from about 1963–1977. And it’s unraveling was a bi-partisan affair.

The final lie is the most pernicious. The idea that the Fairness Doctrine was designed “to maintain truth in journalism” is baldly incorrect. Fairness is not synonymous with truth. Two balanced lies is just as fair as two balanced truths, a fact all too familiar to observers of partisan politics. Furthermore, the FCC recognized that truth is a slippery concept and that government attempts to mandate truth-telling would inevitably violate the First Amendment. Even under the most rigorous Fairness Doctrine regime, one could still lie with abandon.

Indeed, the Fairness Doctrine often enabled lies of political convenience. For example, in 1964 a right-wing radio broadcaster named Dan Smoot accused the Johnson administration of lying about the Gulf of Tonkin incident, which was being used as a pretext for escalation in the Vietnam War. We know today that the administration was dissembling about the incident; Johnson was caught on tape saying, “For all I know, our Navy was shooting at whales out there.” But at the time, the Fairness Doctrine allowed Democratic operatives to demand free airtime from stations that aired Smoot’s allegation with the ultimate goal of convincing station owners to think twice before hosting critics of the administration again.

No, the Fairness Doctrine never had anything to do with “truth in journalism.” It was an attempt to use mandated fairness in broadcasting in order to generate a political consensus around centrist politics, one which excluded voices from both the far Right and Left. We do not “need it back.” The Fairness Doctrine was a fundamentally flawed and easily abused set of regulations that rewarded lies, squelched dissent, and ultimately produced a chilling effect in broadcasting.

These lies and half-truths about the Fairness Doctrine are popular because they evoke nostalgia for an imagined era in a hazy past when our politics were guided by truth, justice, and the American way. Exaggerating the duration of the Fairness Doctrine era, fixing blame for its repeal solely on Reagan, and claiming that it was about maintaining truth in journalism (while forgetting its use as a tool of government censorship) all serve to heighten people’s sense that the Fairness Doctrine could be a reasonable and simple regulatory cure for what ails us today.

And it is far easier to invoke the Fairness Doctrine as a solution to the spread of misinformation and conspiracism in modern media than it is to grapple with the deeper cultural and structural roots of our national dysfunction.