Remember the summer of the shark? That was 2001, when the media, feeding on a few high profile incidents, gave Americans the impression that they faced an outbreak of shark attacks, when in fact shark attacks were down. Something similar may be happening today with piracy.

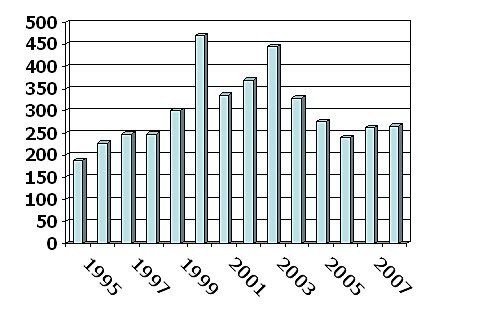

If you’re reading the news these days, you are likely under the impression that an explosion of piracy threatens global shipping. But according to statistics kept by the International Maritime Bureau (IMB) piracy is not occurring at an unusual rate this year. (They define piracy as using force to board or attempt to board a ship to commit a crime.) Piracy is up slightly in the last two years but down since 2005. This year’s 265 attacks (a projection based on three quarters of data) are just 60% of the level recorded in 2003, when there were 445 attacks. On the other hand, as the chart below shows, the 2000s have seen considerably more piracy than the 1990s. And hijacking has increased substantially this year, up from 15 incidents in 2007 to 50 and counting this year.

Here’s a chart showing worldwide incidents of piracy since 1995. The data is from the IMB. The number for 2008 is projected from three quarters of data, so it may be a little off.

In recent years, piracy has more than tripled in the Gulf of Aden and off Somalia — from 21 attacks in 2003 to 63 through three quarters this year. But that growth is not enough to offset the downturn elsewhere. Bangladesh, Indonesia and the Malacca Straits together saw 207 attacks in 2003 but only 65 last year. The total in those waters this year will be even lower. It’s possible that the nature and volume of shipments in the Gulf of Aden along with the prevalence of hijacking there make recent piracy particularly costly. But the IMB’s data, at least, provides little evidence for this claim.

Although the cause of the spike in piracy near Somalia is unclear, it coincides with the fall of the Islamic Courts Union, which was chased from power by an Ethiopian invasion that the United States backed. (If you think it’s obvious that lawlessness in Somalia caused the outbreak of piracy, then explain why decades of anarchy never before produced piracy of this volume.) Most analysts attribute the drop in attacks in Asia to better cooperative efforts to combat piracy and improved economic conditions.

The big reason piracy has increased in this decade is probably because maritime trade itself grew — from 4 billion tons of cargo in 1990 to 7.4 billion tons in 2006, according to the International Maritime Organization. There are more targets. But piracy’s overall effect on trade remains small. One estimate of piracy’s annual cost is $16 billion a year. Some say even that estimate is far too high. Maritime commerce back in 2005 had a total value of $7.8 trillion. Note that even the hijacking of an oil tanker in the Gulf of Aden has not much slowed tanker traffic there.

While we are here, it is also worth addressing the alleged piracy-terrorism nexus. In short, there is no evidence that it exists. (Terrorists hijacking a fishing vessel to get to Mumbai does not constitute a nexus.) What about the fact that Somalia, source of so much piracy, is supposed to be the next big al Qaeda base? The truth is, Somalia never had a significant al Qaeda presence, no more than a few guys.

Because the victims of piracy in the Gulf of Aden are foreign-owned ships and because the effect on U.S. consumers is tiny, this is a problem best left to nations that suffer more direct costs or shippers themselves. Americans should encourage multilateral solutions, but should not confuse the problem with one that has great consequences for their welfare.