Former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers’ review of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in The Twenty-First Century, claims that Mr. Piketty and Emmanuel Saez have documented, “absolutely conclusively, that the share of income and wealth going to those at the very top—the top 1 percent, .1 percent, and .01 percent of the population—has risen sharply over the last generation, marking a return to a pattern that prevailed before World War I.” That statement is false.

Paul Krugman’s review “Why We’re in a New Gilded Age,” claims that “since 1980 the one percent has seen its income share surge again—and in the United States it’s back to what it was a century ago.” That statement is false.

A Pew Research Center report on the same data was titled, “U.S. income inequality, on rise for decades, is now the highest since 1928.” That too is false.

First of all, the Piketty and Saez estimates do not show top 1 percent income shares nearly as high as those of 1916 or 1928 once we use the same measure of total income for both prewar and postwar data.

Second, contrary to Summers, there is no data from Piketty, Saez or anyone else showing that the top 1 percent’s share of wealth “has risen sharply [if at all] over the last generation” — much less exhibited a “return to a pattern that prevailed before World War I.”

Dealing first with income, it is interesting that the first graph in Piketty’s book is about the top 10 percent — not the top 1 percent. Saez likewise writes that “the top decile income share in 2012 is equal to 50.4%, the highest ever since 1917 when the series start.” That is why President Obama said, “The top 10 percent no longer takes in one-third of our [sic] income — it now takes half.” A two-earner New York City family of six with a pretax income of only $110,000 would be in this top 10 percent, and they are certainly not taking “our” income. Regardless whether we examine the Top 10 percent or Top 1 percent, however, it is absolutely dishonest to compare the postwar estimates with prewar estimates.

The Piketty and Saez prewar estimates express top incomes as a share of Personal Income, after subtracting 20% to account for tax avoidance. Postwar estimates, by contrast, express top incomes as a share of only that fraction of income that happens to be reported on individual income tax returns — rather than being unreported, in tax-free savings or assets, or sheltered as retained corporate earnings.

Transfer payments are not counted as income in either series (as though federal cash and benefits were worthless); this distinction is inconsequential for the prewar figures but increasingly important lately. “Total income” as Piketty and Saez define it accounted for just 61.8 percent of personal income in 2012, down from 67 percent in 2000.

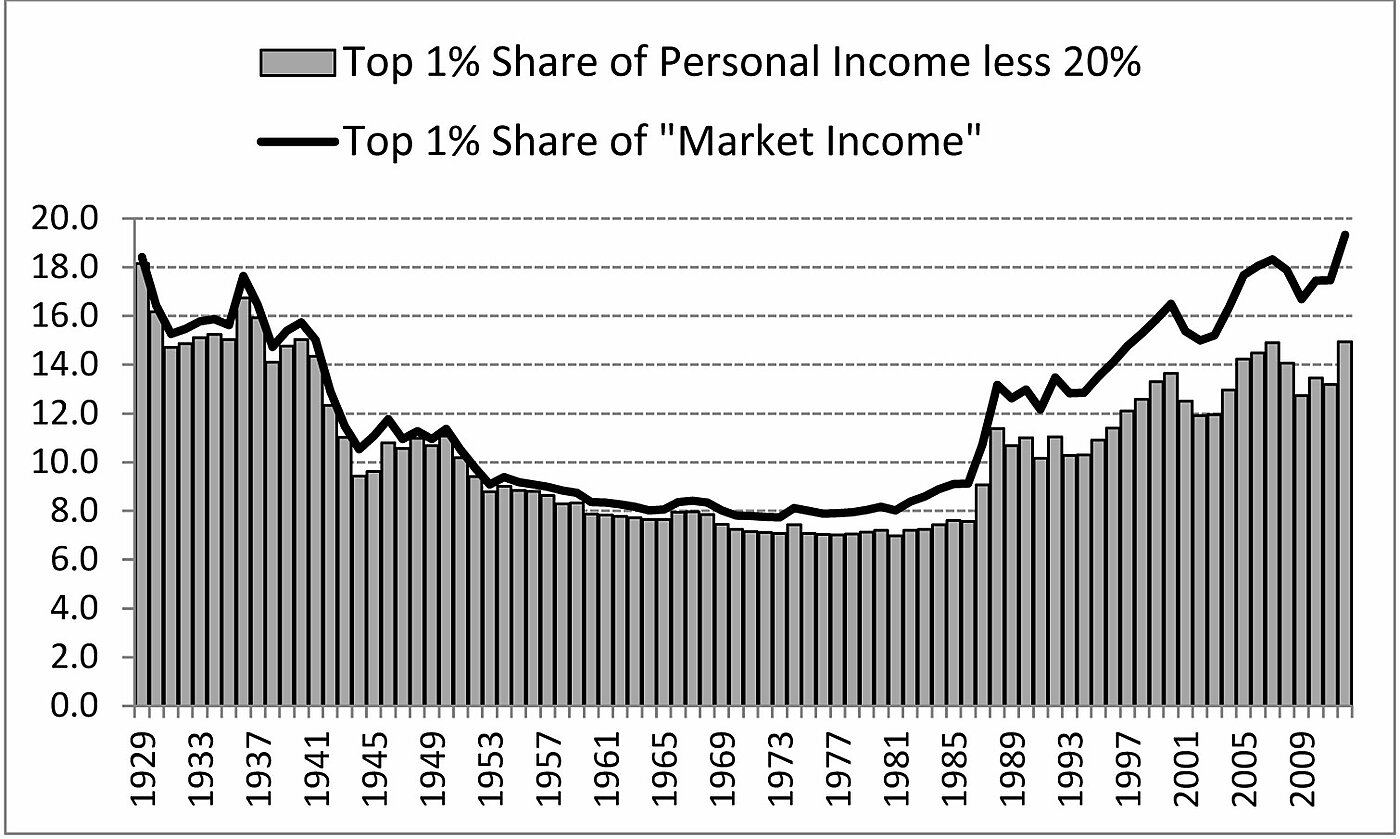

The line in my graph shows the top 1 percent’s share of income as reported by Piketty and Saez. The bars below the line restate top 1 percent shares on a the same consistent basis for all years since 1929 (the earliest available) as a share of what we’ll call “modified personal income” (MPI) — PI minus 20%. Measured on such a comparable basis, the Top 1% share was still 18.2% in 1929 but only 13.2% in 2011.

The 11–13 percent income shares of the top 1 percent since 1988 are not remotely close to the 18.6% Piketty-Saez estimate for 1916 or the record 19.6 percent estimate for 1928. The top 1 percent’s share of MPI did jump to 14.9% in 2012, but that was a fluke. As Saez explained, “part of the surge of top 1% incomes in 2012 could be due to income retiming to take advantage of the lower top tax rates in 2012 relative to 2013 and after.… Retiming of income should produce a dip in top reported incomes in 2013.”

Using modified personal income as the base for both prewar and postwar income shares, the Top 1% share clearly spiked upward after the 1986 Tax Reform, and then fluctuated cyclically between 11 and 13 percent from 1988 to 2011, averaging 12.3 percent.

The fact that few high incomes were reported on individual tax returns from 1932 to 1980 — when top tax rates were 63–91 percent — is entirely consistent with the evidence on “elasticity of taxable income.” [$] It should be no surprise that much more income was reported [$] on individual tax returns when tax rates on high salaries and unincorporated businesses dropped to 28 percent in 1988, or when tax rates on dividends and capital gains fell to 15 percent in 2003. That is exactly what the evidence should lead us to expect.

As Piketty, Saez and Stantcheva explain, “There is a clear negative overall correlation between the top 1% income share and the top marginal tax rate: (a) the top 1% income share was high before the Great Depression when top tax rates were low (except for a short period from 1917 to 1922), (b) the top 1% income share was consistently low between 1932 to 1980 when the top tax rate was uniformly high, (c) the top 1% income share has increased significantly since 1980 after the top tax rate has been greatly lowered. This … suggests that the overall elasticity of reported incomes is high.”

In other words, if top tax rates had not been prohitively high in 1917–22 and 1932–1980 the top 1 percent would have earned and reported much more income and paid more taxes. If tax rates had not been greatly reduced in 1983, 1988 and 2003, the top 1 percent would now be reporting much less income and paying fewer taxes.

What about Wealth — the defining topic of Piketty’s book? Summers conflates wealth and income — claiming Piketty and Saez have shown “absolutely conclusively, that the share of income and wealth [emphasis added] going to those at the very top … has risen sharply over the last generation.” On the contrary, a 2004 paper by Saez and Wojciech Kopczuk found the top one percent’s share of wealth was 38.1% in 1916, 40.29% in 1930, 25.25% in 1960 and 20.79% in 2000.

As they explained, “Top wealth shares … are much lower today than in the pre–Great Depression era.… Findings from the Survey of Consumer Finances … also display hardly any significant growth in wealth concentration since 1995.… Our composition series suggest that by 2000, the top one percent wealth holders do not hold a significantly larger fraction of their wealth in the form of stocks than the average person in the U.S. economy, explaining in part why the bull stock market of the late 1990s has not disproportionately benefited the rich.”

Those who claim the top one percent’s share of total income is now as high as it was in 1916 or 1928 have been deceived by the fact that Piketty and Saez patched together two time series based on different measures of total income. Those who claim the top 1 percent’s share of wealth is now as high as it was in 1916 or 1928 are seriously misinformed or lying.