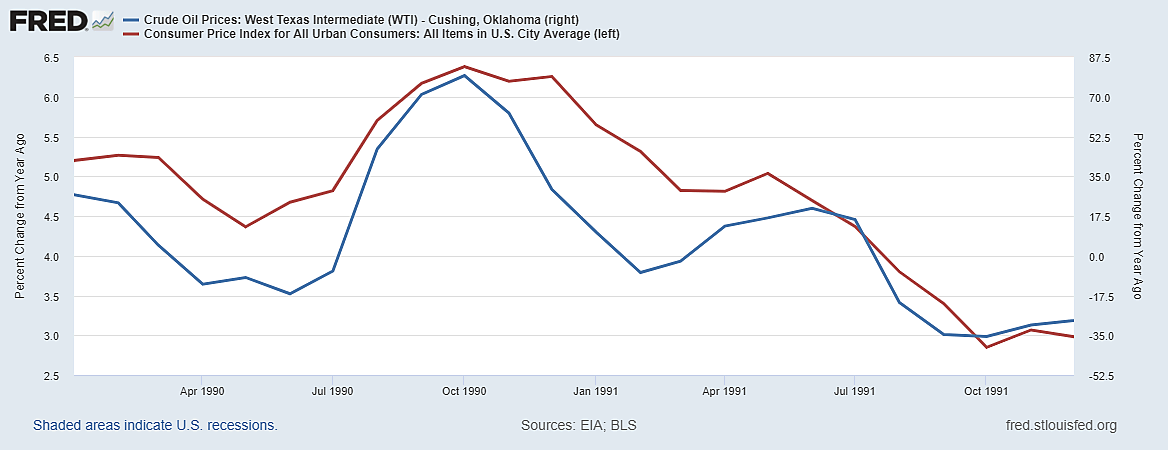

“U.S. Inflation Hit 31-Year High in October as Consumer Prices Jump 6.2%” That should make you wonder: What happened in 1990 to make that October’s year-to-year CPI inflation rate of 6.4% so much like October 2021’s 6.2%?

The first graph compares the 1990–91 year-to-year percentage change in the oil price (79.3% in October) to the tightly linked year-to-year percentage change in the CPI. The price of West Texas crude oil rose from $16.70 a barrel in June to $36.04 in October and the year-to-year CPI marched up in lock step to 6.4%. Then the year-to-year CPI inflation dropped back to 2.8% a year later as crude oil fell below $20. This was no coincidence.

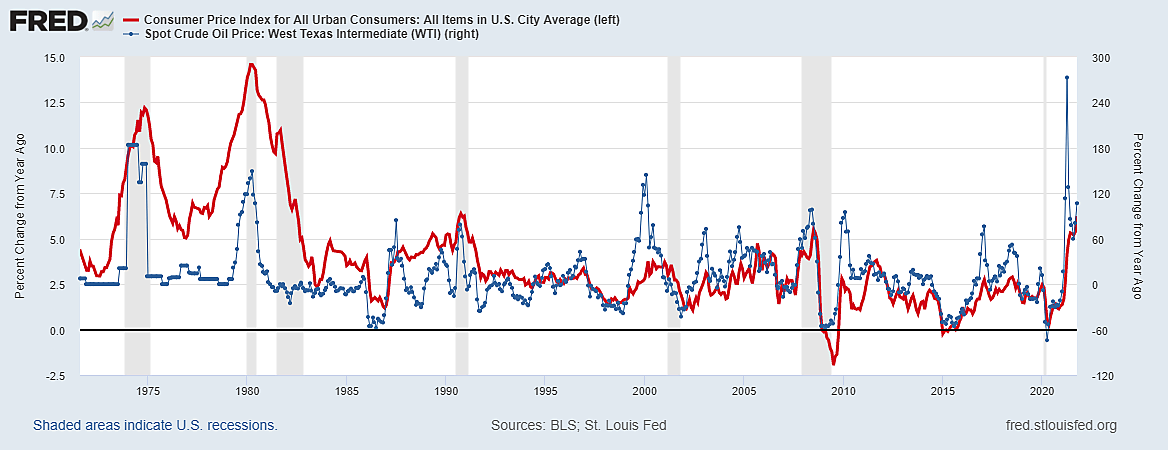

Now, fast forward 31 years. The price of West Texas crude rose 106.8% from October 2020 ($39.40 a barrel) to October 2021 ($81.48). That was an even larger year-to-year percentage change than the Great Recession’s crushing 98.5% increase from July 2007 ($74.18) to July 2008 ($133.93).

The second graph goes back to August 1971 (Nixonomics). It shows that year-to-year percentage changes in the CPI (and all other price indexes) invariably go up and down with year-to-year percentage changes in the price of oil. This happened too regularly to prudently ignore. Higher oil prices also raise non-energy costs such as transportation, paint, and plastics, so even core inflation is affected.

Congress or the White House could do extraordinarily little to prevent or undo the doubling of the oil price, because oil prices (and many food prices) are set in world markets by global supply and demand. Restrictions on U.S. oil and gas drilling are foolishly unhelpful, but the post-lockdown surge in world oil, gas and coal prices was dominated by global demand not local supply.

Past and pending federal “fiscal stimulus” sprees (regardless of their effect on budget deficits) are clearly imprudent when supplies of critical skills and resources are already too tight to meet both private and public demand. But government demand for fossil fuels is not big enough to have much effect on the world price. The Federal Reserve’s incestuous purchases of Treasury IOUs invites more fiscal excess. But higher interest rates could significantly affect world oil demand only by contracting U.S. industry and commerce.

As both graphs show, however, markets are self-correcting. Past oil price spikes also overstated year-to-year inflation statistics, such as the PPI and CPI, but not for long. Oil price spikes always proved transitory because steep energy prices squelch demand and boost supply. Oil prices spikes can also end too abruptly by triggering global recessions—as in 1974, 1979, 1990 and 2008. Recession risk is greater—as Ben Bernanke and others documented in “Systematic Monetary Policy and the Effects of Oil Price Shocks”– if the Fed overreacts to oil-based distortions in headline inflation by raising interest rates on bank reserves too aggressively.

If we do not stop obsessing over widely misunderstood year-to-year percentage changes—and rushing to blame someone at home for a global problem—policymakers could easily repeat bad mistakes.