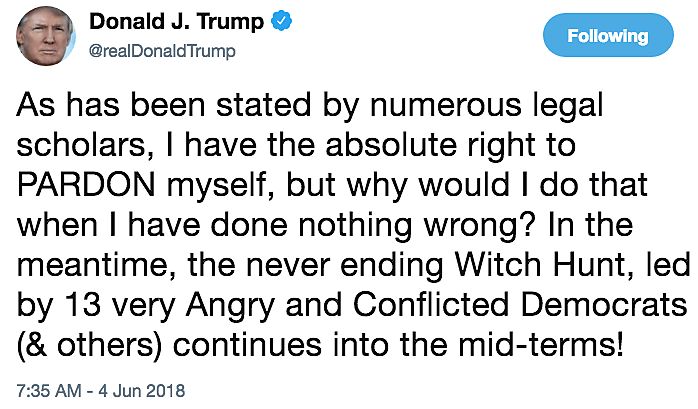

In his prime tweeting time, bright and early last Monday, President Trump proclaimed:

“Numerous legal scholars?” I harrumphed to myself: “come on.” Given that no president has ever been crazy enough to try it, the self-pardon is a novel question of constitutional law. When I first looked into the issue last year, I could find only two law review articles devoted to the subject, one pro, one con.

But sure enough, in the week that followed, “numerous legal scholars” chimed in with impressive confidence. Jack Goldsmith has a useful roundup over at Lawfare, noting that while the “constitutional text does not speak overtly to the issue and there is no judicial precedent on point… that doesn’t stop people from voicing strong opinions” on each side of the issue.

Since Goldsmith’s post, two more right-leaning legal heavyweights have made the case for the self-pardoning power. In the Wall Street Journal, Richard Epstein insists that Article II, Section 2, allows the president to issue himself a get-out-of-jail-free card, but—not to worry—we’ll always have “the powerful check public opinion places on the president.” And in a Washington Post oped that ran Friday, former 10th Circuit judge Michael W. McConnell argues that “presidents do have the constitutional authority to pardon themselves.”

The main piece of evidence McConnell offers to support that proposition is a September 15, 1787 exchange between Edmund Randolph and James Wilson at the Constitutional Convention. As captured in Madison’s notes, it went like this:

Mr. RANDOLPH moved to “except cases of treason” [from the reach of the pardon power]. The prerogative of pardon in these cases was too great a trust. The President may himself be guilty. The Traytors may be his own instruments.

Col. MASON supported the motion.

Mr. Govr. MORRIS had rather there should be no pardon for treason, than let the power devolve on the Legislature.

Mr. WILSON. Pardon is necessary for cases of treason, and is best placed in the hands of the Executive. If he be himself a party to the guilt he can be impeached and prosecuted.

Q.E.D., apparently. “The framers of the Constitution thus specifically contemplated and debated the prospect that a president might be guilty of an offense and use the pardon power to clear himself,” McConnell writes.

That is… not at all clear. The Randolph-Wilson exchange could just as easily be read to refer to the president’s power to pardon co-conspirators (the “Traytors” he’s in league with), as in a similar exchange, also featuring George Mason, at the Virginia Ratifying Convention the next summer. Renewing Randolph’s objection, Mason warned that the president “may frequently pardon crimes which were advised by himself…. If he has the power of granting pardons before indictment, or conviction, may he not stop inquiry and prevent detection?” (If he’d understood the September 15 conversation the way McConnell does, Mason might have strengthened the point by adding “he can even pardon himself!”)

Professor McConnell insists that when Wilson said the president “can be impeached and prosecuted,” he meant “prosecuted before the Senate,” i.e., in an impeachment trial. Maybe! But what makes him so sure? It seems just as likely that Wilson is referring to criminal prosecution, per (what became) Article I, sec. 3, cl. 7, under which a civil officer convicted in an impeachment trial “shall nevertheless be liable and subject to Indictment, Trial, Judgement and Punishment, according to Law.”

In the leading (possibly lone) law review article supporting the constitutionality of self-pardons, the authors have a different take on the Randolph-Wilson colloquy. In their reading of the passage: “while not addressing self-pardons directly, there is a clear indication that pardons were available to protect one’s cohorts in a treason attempt. Wilson further argued that if the President committed treason, he could be impeached and even prosecuted after impeachment” [emphasis added]. Brian Kalt, author of the best full-length case against the presidential self-pardon, points out that “When Randolph suggested the possibility of presidential treason, his solution was to eliminate the treason pardon, not to prohibit self-pardons, which would have been a more direct solution.” He further notes that “the self-pardon was nowhere mentioned in the debates.”

But let’s say McConnell is spot-on about what the Randolph-Wilson exchange signified. If so, we have, at most, one example of the Framers implicitly recognizing a presidential power to self-pardon, in a forum governed by secrecy, whose deliberations weren’t directly available to the ratifiers, who, in turn showed no evidence of sharing that understanding. On the other side, we have textual ambiguity, historical silence, and the fact that the underlying rationale for the pardon power—“humanity and good policy”—would seem to be weakest when the president’s letting himself off the hook. Is that one piece of evidence enough? Is that how originalism works? Libertarian legal scholar Randy Barnett has argued the Constitution should be interpreted in light of a “Presumption of Liberty.” But what interpretive principle is at work here? In disputed cases, a tie goes to the president? A Presumption of Executive Power?

Neither Epstein nor McConnell address the best argument against the constitutionality of the self-pardon, one based on the text of Article II, Section 2 itself: The President shall have Power to grant Reprieves and Pardons for Offenses against the United States.” “Grant” implies a grantor and a grantee, “pardon,” a donor and a recipient. The power is “inherently bilateral,” the argument goes.

McConnell’s right, however, that some of the arguments on the other side aren’t very good. The Nixon-era Justice Department memorandum denying a self pardon power, he notes, rests on a single line of analysis, rejecting the power because it violates “the fundamental rule that no one may be a judge in his own case.”

But here’s an interesting wrinkle: that same memo suggests—far more credibly—that the president can accomplish the same end, via the 25th Amendment, provided the vice president is willing to go along.

This is a very different “25th Amendment Solution” than the one that Never Trumpers and #Resistance leaders favor. In their version, Mike Pence and a majority of the Cabinet or “such other body as Congress may by law provide” invoke Section 4 of the amendment to declare the president “unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office.”

The DOJ memo focuses instead on Section 3, which allows the president to make the call himself, stepping aside temporarily while the vice president steps in. So far, Section 3 has served as the Constitution’s “Colonoscopy Clause,” invoked mainly when presidents are getting their polyps snipped. According to the memo, however,

A different approach to the pardoning problem could be taken under Section 3 of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment. If the President declared that he was temporarily unable to perform the duties of his office, the Vice President would become Acting President and as such he could pardon the President. Thereafter the President could either resign or resume the duties of his office.

As “Acting President,” the veep accedes to all the powers of the office, including the power to pardon. If Trump could strike a deal with Mike Pence, then a de facto self-pardon, minus the legal uncertainty, could be accomplished in an afternoon. Nor would he run any great risk if Pence refused to hold up his end of the corrupt bargain. Either way, Trump could reassume his post as quickly as he could fire off a letter to Congress.

As with the #Resistance version, this twist on the 25th Amendment Solution is the stuff of political thrillers: it’s quite unlikely to happen in real life. Both versions require Pence’s cooperation to get off the ground. In the Section 4 scenario, he has to be willing to shiv his boss; the Section 3 scheme requires Pence to torch his own political career. Still, if you had to pick which “Solution” was more likely… take a look at one of those Cabinet meeting videos, then place your bet.