With the COVID-19 pandemic (hopefully) in the rearview mirror, it is time to reevaluate the Fed’s broadened mandate. While many policymakers want the Fed to fix everything from inflation and financial instability to unemployment and climate change, this article explains why the Fed should do less, not more.

At the onset of the pandemic in 2020, the Federal Reserve committed itself to achieving “broad-based and inclusive” employment. Presumably, this implies not just stabilizing the economy-wide unemployment rate, but also using policy tools to affect distributional employment across a variety of socioeconomic factors.

Leaving aside the question of why a government agency tasked with benefiting all US citizens should pick winners and losers in the labor market, there is no clear tool the Fed possesses to affect such distributional outcomes.

Even its effect on the overall employment rate is debatable. For years, the Federal Reserve itself insisted that the “maximum level of employment is largely determined by nonmonetary factors that affect the structure and dynamics of the job market.”

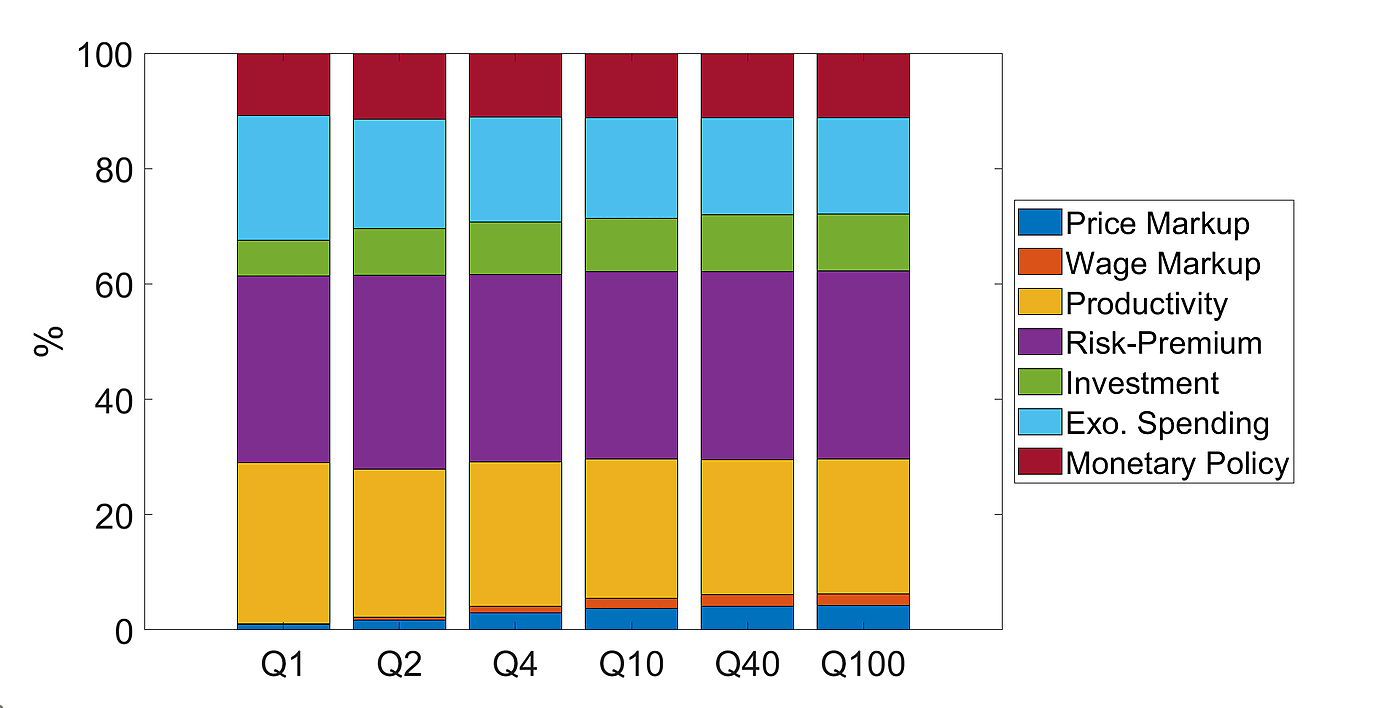

As I showed in a recent CMFA working paper, the Fed has historically only accounted for 10 percent of inflation and 20 percent of output at peak efficacy. As Figure 1 below shows, if output growth (inversely related to the unemployment rate) is broken down into its constituent factors from 1960 to 2019, the Fed’s actions barely accounted for 10 percent of GDP fluctuations.

Most of the output growth (and thereby the unemployment rate) was determined by productivity shocks or demand factors such as changes to consumers’ risk preferences and fiscal spending.

So how does the Fed hope to achieve its distributional goals? A recent Reuters article evaluating the Fed’s pandemic policymaking offers an answer—keep labor markets tight since tight labor markets correlate with a narrowed race gap in unemployment. In other words, by (somehow) ensuring that there are more jobs than workers, the Fed should “produce more “equitable outcomes,” where “the unemployment rate gap between Blacks and whites” narrows. There are several problems with this approach.

Firstly, to keep labor markets artificially tight, the Fed must keep its policy stance overly loose. And that’s what the Fed did starting in 2020, when rates were near zero despite economic conditions warranting adjustments. In usual times, this may not have had severe effects. However, the Fed’s hesitancy to raise rates with rising inflation (which it labeled “transitory”) led to a major discrepancy between its “broad-based” goals and its mandate to achieve price stability. As another CMFA working paper shows, actual interest rates and their “optimal” values drastically diverged during the Powell administration. The Fed was 20 months too late in raising its rate target. Consequently, the target rate was over 800 basis points away from optimal in 2021. Undoubtedly this was a factor that entrenched inflation.

Additionally, tight labor markets have negative effects on the economy overall. Most importantly, they can lead to a shortage of workers and an overheated economy, adding further upward pressure to an already high and entrenched inflation rate. (This problem is aside from a built-in bias of the economy reverting to its natural unemployment rate regardless of the Fed’s attempts, with only inflation remaining high.)

Good economic outcomes for consumers across all demographics is a desirable goal. But to purposely try to overheat the economy, with little reason to think that doing so will help either a subgroup or the wider population, is not the solution. The Fed is aware of this problem. As former vice-chair Don Kohn recently stated:

• Probing for maximum employment can have considerable advantages, but it deliberately runs inflation risks.

• The new 2020 monetary policy framework and its implementation in forward guidance embodied “probing”; the framework is deliberately asymmetric toward probing.

• But they also illustrated the potential costs by inducing the FOMC to wait too long to raise interest rates, contributing to the extent and persistence of inflation in 2021, 2022, and 2023.

• The 2024–25 re-examination of the framework needs to look closely at the costs and benefits of probing and to address a broader range of possible economic circumstances than did the 2020 framework.

Don Kohn’s advice is correct and mirrors our recommendations at CMFA. The Fed should do less, not more. Its policymaking should be clear, concise, and objective, none of which has been the norm for the Fed.