Earlier today I posed to Market Monetarists the following questions: “If a substantial share of today’s high unemployment really is due to a lack of spending, what sort of wage-expectations pattern is informing this outcome?…Can it really be the case that NGDP (and equilibrium wage rate) expectations continue to race ahead of reality, even when that reality involves what would normally be considered a perfectly respectable, if not excessive, growth rate of overall spending? How can this be?”

When I posed these questions I had no answer in mind; on the contrary I doubted that they could be answered without appealing to some extremely odd labor market behavior.

Having done a bit more thinking since, I now believe I have a better grasp of why the combination of an NGDP growth revival and more modest wage inflation hasn’t sufficed to eliminate cyclical (demand-shortage based) unemployment. My further reflections make me more inclined to see merit in Market Monetarists’ arguments for more accommodative monetary policy. But they also leave me as puzzled as before regarding the expectations-formation processes driving observed patterns of wage-rate adjustment. More specifically, they bring to light a degree of wage-inflation inertia that seems, on its face, difficult to square with the usual assumption that market participants behave rationally.

Previously I observed that it has been about two years since NGDP recovered its pre-Lehman’s level, and that it has been growing at between 4 and 5 percent ever since. I also noted that the rate of increase in hourly wages has fallen persistently since the crash, and is now half what it was before then. So, why haven’t these facts together added up to the elimination of cyclical unemployment?

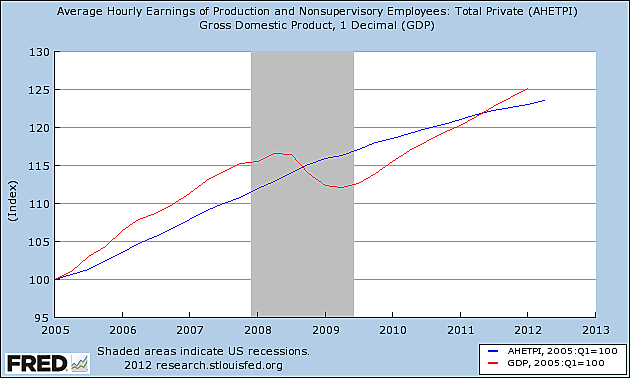

My partial answer to those questions is one best captured by the following graph, showing index values (with 1/1/2003=100) for hourly wages and NGDP since 2005:

Here one can clearly see how, while NGDP plummeted, hourly wages kept right on increasing, albeit at an ever declining rate. Allowing for compounding, this difference sufficed to create a gap between wage and NGDP levels far exceeding its pre-bust counterpart, and large enough to have been only slightly reduced by subsequent, reasonably robust NGDP growth, notwithstanding the slowed growth of wages.

The puzzle is, of course, why wages have kept on rising at all, despite high unemployment. Had they stopped increasing altogether at the onset of the NGDP crunch, wages and total spending might have recovered their old relative positions about two years ago. That, presumably, would have been too much to hope for. But if it is unreasonable to expect wage inflation to stop on a dime, is it not equally perplexing that it should lunge ahead like an ocean liner might, despite having its engines put to a full stop?

ADDENDUM (July 9, 2012): It turns out that the graph I concocted appears after all to have misled me (I confess I was apparently to willing to be convinced that there might be a case for further NGDP stimulus after all); playing around with it further (by using the same scale for both plots and letting 1/1/2005=100), I come up with another that actually reinforces the position I took in my original post:

Tom Dougherty, below and at TheMoneyIllusion, gets a similar result using a newer and more comprehensive hourly compensation index.

In light of these further findings, I’m back to my original question: has the Fed, despite the still high level of unemployment, already done all that it ought to do in the way of monetary easing despite the still high level of unemployment?