President Donald Trump and U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson met on the sidelines of the G7 summit this weekend, and among the issues discussed was a possible U.S.-U.K. free trade agreement. In public remarks Johnson made clear his desire that such a deal include cabotage privileges for U.K.-flagged ships:

PRESIDENT TRUMP: We’re having very good trade talks between the UK and ourselves. We’re going to do a very big trade deal — bigger than we’ve ever had with the UK.

And now, they won’t have it. At some point, they won’t have the obstacle of — they won’t have the anchor around their ankle, because that’s what they had. So, we’re going to have some very good trade talks and big numbers.

PRIME MINISTER JOHNSON: Talking of the anchor — talking of the anchor, Donald, what we want is for our ships to be able to take freight, say, from New York to Boston, which at the moment they can’t do. So, we want cabotage. How about that?

PRESIDENT TRUMP: Many things — many things we’re talking about.

PRIME MINISTER JOHNSON: That would be a good thing.

Preventing British ships from transporting goods between two U.S. ports is the Jones Act. Passed in 1920, the law restricts domestic waterborne transport to vessels meeting four conditions: they must be U.S.-built, U.S.-flagged, at least 75 percent U.S.-owned, and at least 75 percent U.S.-crewed.

Given Johnson’s comments, it seems likely that British trade negotiators will seek an exemption from this law for U.K.-flagged ships. If granted, their U.S. counterparts will surely demand the removal of various trade barriers to the $2.6 trillion U.K. economy. For Americans this would be an economic twofer, providing them access to a wider range of transport options as well as expanded export opportunities.

Unfortunately, history does not augur in favor of such an outcome. When presented with demands for Jones Act relief U.S. trade negotiators have invariably refused to cede even an inch of ground—an intransigence which reflects the power of the lobbyists who back the law. Indeed, during bilateral trade negotiations with Canada in the 1980s the Jones Act lobby was able to persuade more than half the members of the Senate and House to sign resolutions declaring the Jones Act off the table.

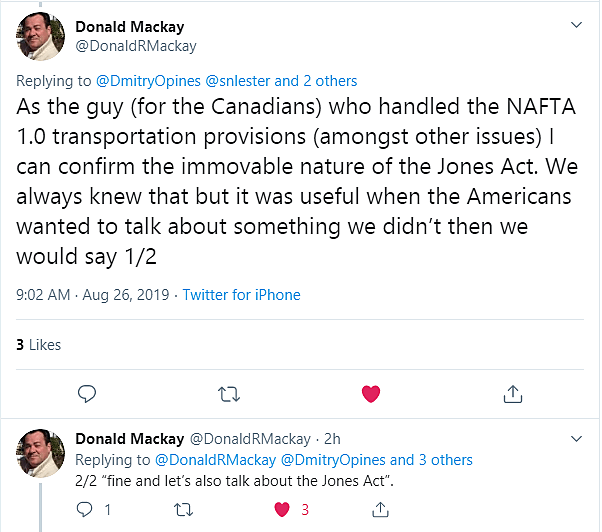

But there was a price to be paid. Not only were Americans denied the ability to use Canadian vessels for domestic transport but—as a former Canadian diplomat points out—the Jones Act was used as a means to deflect from areas where Canadians were loath to part with their own protectionist policies:

Americans are still paying the price for Jones Act protectionism. Continued U.S. obstinacy over the law in trade negotiations is undoubtedly met with corresponding moves from its negotiating partners. That’s how the game is played.

During talks that eventually resulted in the U.S.-South Korea free trade agreement, for example, South Korea—home to one of the world’s largest shipbuilding industries—no doubt raised the issue of the Jones Act’s U.S.-build requirement. U.S. negotiators did not accommodate them, and it’s a safe assumption that barriers to the South Korean economy which otherwise could have been removed were left in place (rice, which was specifically excluded from the deal by South Korea, seems one strong possibility).

This is just another one of the myriad ways in which the Jones Act harms the United States. These harms include: higher transportation costs; increased congestion and highway maintenance costs; more pollution; the inability of Americans to buy U.S. products; and increased barriers to U.S. exports from our trading partners. The tally from these various costs is surely dizzying.

Boris Johnson has done President Trump a favor. With the Jones Act now on the negotiating table, an opportunity has been presented to expand economic freedom at home and increase export opportunities for U.S. businesses abroad. It’s one that Trump should seize.