Members of the public should be able to access the body camera footage related to Tuesday’s police-involved shooting that left Keith Scott dead and prompted violent protests in Charlotte, North Carolina. But we shouldn’t be under any illusion that everyone who watches the footage will arrive at the same opinion about the police officer’s behavior. Two people can watch the same video and come to different moral conclusions. A study on video footage that proved instrumental in a Supreme Court case helps illustrate this fact.

In Scott v. Harris (2007) the Supreme Court considered whether a police officer (Scott) had violated the Fourth Amendment when he deliberately ran Harris’ car off the road during a high-speed chase, which resulted in Harris being left a quadriplegic. An 8–1 majority found that, “a police officer’s attempt to terminate a dangerous high-speed car chase that threatens the lives of innocent bystanders does not violate the Fourth Amendment, even when it places the fleeing motorist at risk of serious injury or death.”

Dash camera footage played an important role in the Court’s deliberations. In fact, Scott v. Harris has been called the Court’s first “multimedia cyber-opinion,” with Justice Scalia citing the URL to the dash camera video in the opinion, noting, “We are happy to allow the videotape to speak for itself.”

Scalia described what the dash camera video shows as follows:

There we see respondent’s vehicle racing down narrow, two-lane roads in the dead of night at speeds that are shockingly fast. We see it swerve around more than a dozen other cars, cross the double-yellow line, and force cars traveling in both directions to their respective shoulders to avoid being hit. We see it run multiple red lights and travel for considerable periods of time in the occasional center left-turn-only lane, chased by numerous police cars forced to engage in the same hazardous maneuvers just to keep up. Far from being the cautious and controlled driver the lower court depicts, what we see on the video more closely resembles a Hollywood-style car chase of the most frightening sort, placing police officers and innocent bystanders alike at great risk of serious injury.

During oral argument Justice Alito also noted the footage, prompting this exchange:

Justice Alito: […] I looked at the videotape on this. It seemed to me that he created a tremendous risk of drivers on that road. Is that an unreasonable way of looking at the — at this tape?

Justice Scalia: He created the scariest chase I ever saw since “The French Connection.”

(Laughter.)

Justice Scalia: It is frightening.

Yet Justice Stevens, the sole dissenter in the case, rejected the “Hollywood-style car chase” description and came to a different view:

At no point during the chase did respondent pull into the opposite lane other than to pass a car in front of him; he did the latter no more than five times and, on most of those occasions, used his turn signal. On none of these occasions was there a car traveling in the opposite direction. In fact, at one point, when respondent found himself behind a car in his own lane and there were cars traveling in the other direction, he slowed and waited for the cars traveling in the other direction to pass before overtaking the car in front of him while using his turn signal to do so. This is hardly the stuff of Hollywood. To the contrary, the video does not reveal any incidents that could even be remotely characterized as “close calls.”

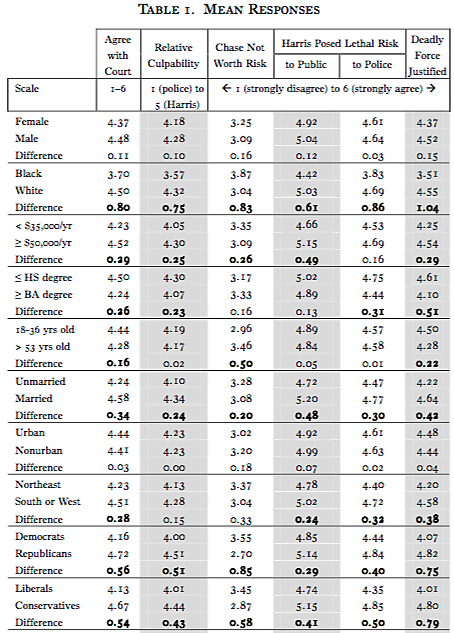

Law professors at Yale, Temple, and George Washington University showed the Scott v. Harris video to a diverse sample of 1,350 Americans, asking them a range of questions about the chase. They found that while a majority did agree with the Court’s ruling, some groups sided with the driver more strongly than others:

Our subjects didn’t see things eye to eye. A fairly substantial majority did interpret the facts the way the Court did. But members of various subcommunities did not. African Americans, low-income workers, and residents of the Northeast, for example, tended to form more pro-plaintiff views of the facts than did the Court. So did individuals who characterized themselves as liberals and Democrats.

A table from the study showing the variety of opinions on the chase by demographic is below:

Clearly, it’s possible for two people to see the same video footage and come to different conclusions. While it’s important for body camera footage of deadly police encounters to be made public we shouldn’t be under the impression that everyone will interpret the footage the same way. Nonetheless, body camera footage will make it easier to show where people think the line between reasonable and unreasonable use of force should be drawn.