Sweden punches way above its weight in debates about economic policy. Leftists all over the world (most recently, Bernie Sanders) say the Nordic nation is an example that proves a big welfare state can exist in a rich nation. And since various data sources (such as the IMF’s huge database) show that Sweden is relatively prosperous and also that there’s an onerous fiscal burden of government, this argument is somewhat plausible.

A few folks on the left sometimes even imply that Sweden is a relatively prosperous nation because it has a large public sector. Though the people who make this assertion never bother to provide any data or evidence.

I have five responses when confronted with the why-can’t-we-be-more-like-Sweden argument.

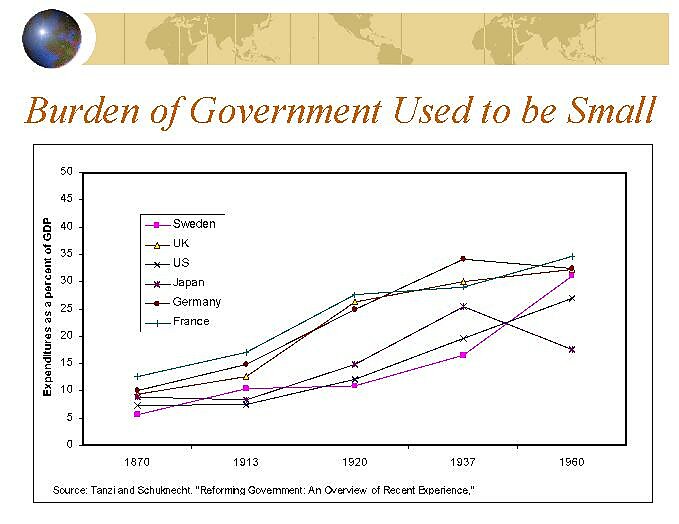

- Sweden became rich when government was small. Indeed, until about 1960, the burden of the public sector in Sweden was smaller than it was in the United States. And as late as 1970, Sweden still had less redistribution spending that America had in 1980.

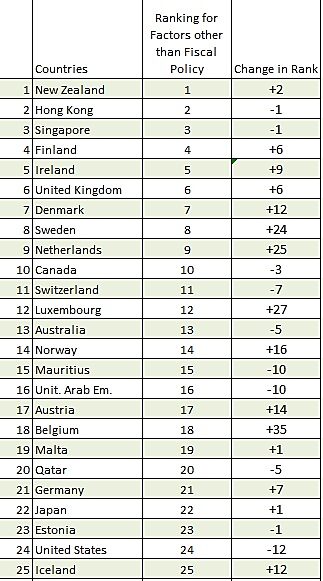

- Sweden compensates for bad fiscal policy by having a very pro-market approach to other areas, such as trade policy, regulatory policy, monetary policy, and rule of law and property rights. Indeed, it has more economic freedom than the United States when looking an non-fiscal policies. The same is true for Denmark.

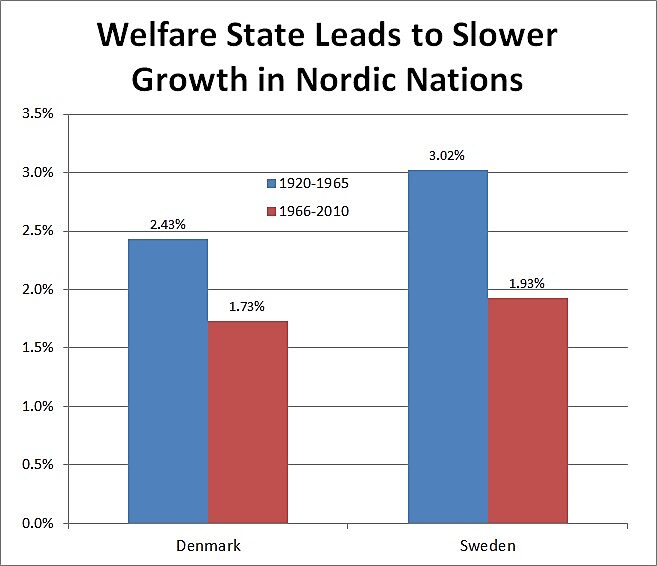

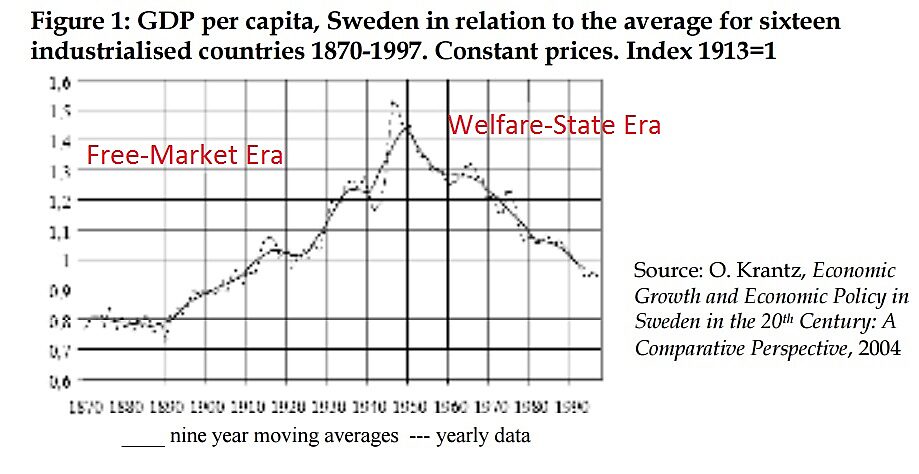

- Sweden has suffered from slower growth ever since the welfare state led to large increases in the burden of government spending. This has resulted in Sweden losing ground relative to other nations and dropping in the rankings of per-capita GDP.

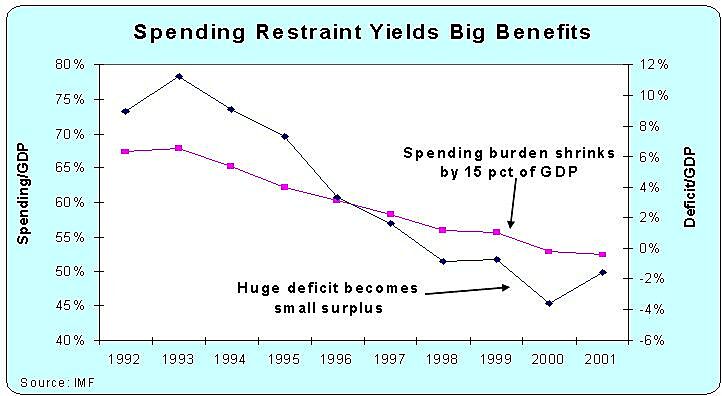

- Sweden is trying to undo the damage of big government with pro-market reforms. Starting in the 1990s, there have been tax-rate reductions, periods of spending restraint, adoption of personal retirement accounts, and implementation of nationwide school choice.

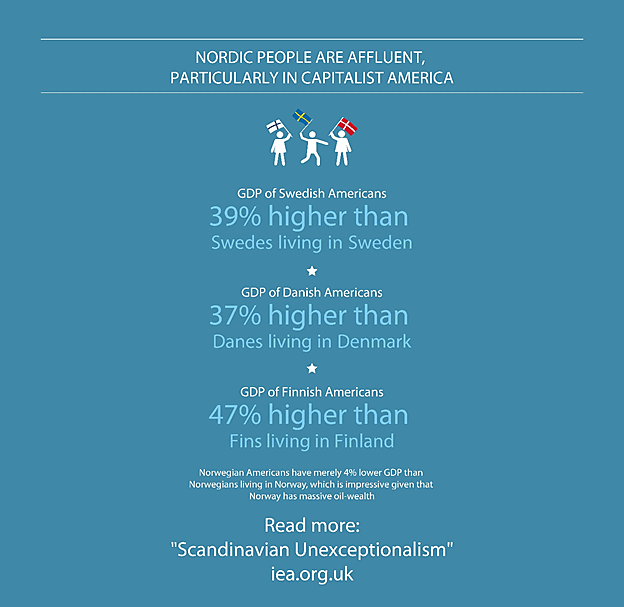

- Sweden doesn’t look quite so good when you learn that Americans of Swedish descent produce 39 percent more economic output, on a per-capita basis, than the Swedes that stayed in Sweden. There’s even a lower poverty rate for Americans of Swedish ancestry compared to the rate for native Swedes.

I think the above information is very powerful. But I’ll also admit that these five points sometimes aren’t very effective in changing minds and educating people because there’s simply too much information to digest.

As such, I’ve always thought it would be helpful to have one compelling visual that clearly shows why Sweden’s experience is actually an argument against big government.

And, thanks to the Professor Deepak Lal of UCLA, who wrote a chapter for a superb book on fiscal policy published by a British think tank, my wish may have been granted. In his chapter, he noted that Sweden’s economic performance stuttered once big government was imposed on the economy.

Though the Swedish model is offered to prove that high levels of social security can be paid for from the cradle to the grave without damaging economic performance, the claim is false (see Figure 1). The Swedish economy, between 1870 and 1950, grew faster on average than any other industrialised economy, and the country became technologically one of the most advanced and richest in the world. From the 1950s Swedish economic growth slowed relative to other industrialised countries. This was due to the expansion of the welfare state and the growth of public – at the expense of private – employment.57 After the Second World War the working population increased by about 1 million: public employment accounted for c. 770,000, private accounted for only 155,000. The crowding out by an inefficient public sector of the efficient private sector has characterised Sweden for nearly half a century.58 From being the fourth richest county in the OECD in 1970 it has fallen to 14th place. Only in France and New Zealand has there been a larger fall in relative wealth.

And here is Figure 1, which should make clear that what’s good in Sweden (rising relative prosperity) was made possible by the era of free markets and small government, and that what’s bad in Sweden (falling relative prosperity) is associated with the adoption and expansion of the welfare state.

But just to make things obvious for any government officials who may be reading this column, I augment the graph by pointing out (in red) the “free-market era” and the “welfare-state era.”

As you can see, credit for the chart actually belongs to Professor Olle Krantz. The version I found in Professor Lal’s chapter is a reproduction, so unfortunately the two axes are not very clear. But all you need to know is that Sweden’s relative economic position fell significantly between the time the welfare state was adopted and the mid 1990s (which presumably reflects the comparative cross-country data that was available when Krantz did his calculations).

You can also see, for what it’s worth, that Sweden’s economy spiked during World War II. There’s no policy lesson in this observation, other than to perhaps note that it’s never a good idea to have your factories bombed.

But the main lesson, which hopefully is abundantly clear, is that big government is a recipe for comparative decline.

Which perhaps explains why Swedish policymakers have spent the past 25 years or so trying to undo some of those mistakes.