Citing the work of David Burton and Richard Rahn, I warned last July about the dangerous consequences of allowing governments to create a global tax cartel based on the collection and sharing of sensitive personal financial information.

I was focused on the danger to individuals, but it’s also risky to let governments obtain more data from businesses.

Remarkably, even the World Bank acknowledges the downside of giving more information to governments.

Here are some blurbs from the abstract of a new study looking at what happens when companies divulge more data.

Relying on a data set of more than 70,000 firms in 121 countries, the analysis finds that disclosure can be a double-edged sword. …The findings reveal the dark side of voluntary information disclosure: exposing firms to government expropriation.

And here are some additional details from the full report.

…disclosure has important costs in allowing exposure to government expropriation… We show that accounting information disclosure can be detrimental to firm development… Such disclosure allows corrupt bureaucrats to gain access to firm-level information and use it for endogenous harassment. …once firm information is disclosed, the threat of government expropriation is widespread. Information disclosure thus allows rent-seeking bureaucrats to gain access to the disclosed information and use it to extract bribes. …Our paper offers a vivid illustration that an important hindrance to institutional development—here in the form of adopting information disclosure—is government expropriation. …The results are thus supportive of Acemoglu and Johnson (2005) on the overwhelming importance of constraining government expropriation in facilitating economic development.

Yet this doesn’t seem to bother advocates of bigger government.

Indeed, they’re using a Paris-based international bureaucracy to push a “base erosion and profit shifting” initiative designed to produce global rules that would give governments far greater access to business data.

Their goal is to extract more money openly with tax policy rather than surreptitiously with bribes, but the net effect will be just as bad for the global economy.

A new study from the Center for Freedom and Prosperity has the disturbing details.

Under direction of the G20, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) began two years ago a major initiative on “base erosion and profit shifting” (BEPS). …Through the BEPS project, the OECD is continuing its war against tax competition.

For all intents and purposes, politicians from high-tax nations are using the G20 and OECD to undermine the liberalizing force of tax competition.

They want to rewrite international tax policy to prop up nations with uncompetitive tax systems.

[BEPS] would…lead to an overall higher tax environment as politicians freed from the pressures of global tax competition inevitably raise rates to levels last seen in the early 1980s, when reforms by Reagan and Thatcher sparked a global reduction in corporate tax rates that has continued to this day. Through tax competition, the average corporate tax rate of OECD nations declined from almost 50% in 1981 to 25% in 2015. …The [BEPS] Action Plan…considers the benefits of tax competition to be the real problem, explaining that “there is a reduction of the overall tax paid by all parties involved as a whole.” The prospect of there being less money to be spent by politicians is perceived as a problem to be solved.

Even though there’s no evidence of a problem, even from the perspective of revenue-hungry politicians.

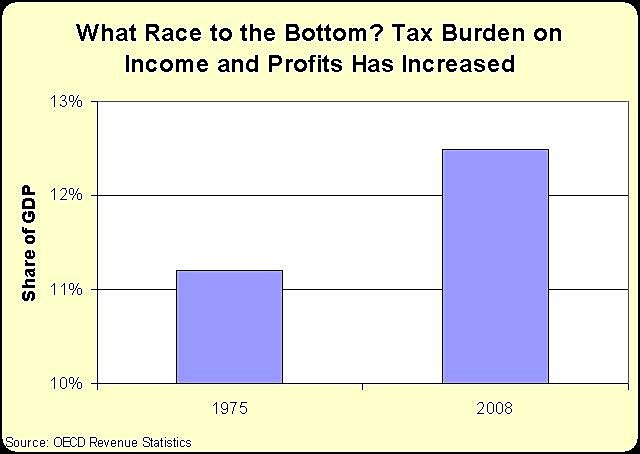

Particularly since the OECD’s own data shows that corporate tax revenue keeps increasing, as noted in the CF&P study.

The OECD’s BEPS Report itself undercuts the argument that there is a pressing need for a global response when it acknowledges that “revenues from corporate income taxes as a share of GDP have increased over time.” Likewise, the Action Plan admits when discussing hybrid mismatch that “it may be difficult to determine which country has in fact lost tax revenue.”

So BEPS isn’t a response to the nonexistent problem of falling revenue. Instead, the real goal is to make it easier to impose higher tax rates and change other rules to raise additional revenue.

Even if the required policies have very troubling implications. As part of this new campaign against tax competition, here’s some of what the OECD is seeking.

Proposed recommendations for transfer-pricing documentation and country-by-country reporting, for instance, feature broad reporting requirements that go far beyond what is required for purposes of tax collection. …Information contained in the local and master files are particularly vulnerable, since it would take a breach in only a single jurisdiction for it to be exposed. The OECD makes assurances for the confidentiality of these reports, but they are empty promises. Such government assurances of privacy protection are contradicted by experience and the long history of leaks of taxpayer information. In the United States alone tax data has frequently been exposed thanks to inadequate safeguards, or even released by officials to attack political opponents. …Even without malicious intent, governments are ill equipped to protect sensitive information from outside access. …As poor as the United States has proven at protecting privacy, there are likely to be nations even more vulnerable. Through the master file and other reporting mechanisms, BEPS will demand of corporations propriety information and other sensitive data that they have every right to keep private.

Requiring more information is just one part of BEPS.

There are many other elements, all of which are designed to facilitate higher tax burdens. Indeed, the Wall Street Journal warned that, “this is an attempt to limit corporate global tax competition and take more cash out of the private economy.”

But as bad as BEPS is now, the study from the Center for Freedom and Prosperity explains it will get worse over time.

Of particular relevance for understanding the BEPS initiative is the pattern demonstrated by the OECD during the course of this campaign. After each recommendation was widely adopted – typically under duress in the case of low-tax jurisdictions – the OECD immediately pushed a new requirement that was more radical and invasive than the last. First was a call to adopt a certain number of Tax Information Exchange Agreements and a standard of information exchange upon request, then a peer-review process whereby tax policies are judged according to the standards of high-tax welfare states. Then, after years of meetings and costly compliance efforts, the old standard for information exchange upon request was replaced with a call for global automatic exchange.

The OECD’s strategy of moving the goalposts is worth noting because the BEPS project almost certainly will evolve in ways that enable ever-higher tax burdens.

I predicted back in 2013 that the end result will be “global formula apportionment,” a system that would enable dramatically higher tax burdens on the business community.

And I’m sticking with that prediction, in part because that’s what would be in the interests of politicians from high-tax nations. If national governments were able to tax on the basis of what companies sold inside their borders, regardless of how much income actually was being earned, there would be very little competitive pressure to keep tax rates reasonable.

Politicians could push corporate tax rates back up to 50 percent, or even higher.

The folks on the left certainly would like that kind of system. Here are some excerpts from a CNN story.

It’s time for a complete overhaul of the global tax system to ensure each company pays their fair share, says Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz. …“Multinational corporations act and therefore should be taxed as single and unified firms. It is time for our [political] leaders to be bold,” Stiglitz said. …Stiglitz said that creating a new worldwide tax system is realistic, but all nations would have to work together to agree rules and close loopholes. The group of economists said in a statement that it was critical to “curb tax competition to prevent a race to the bottom.” Developed nations should take the first step by agreeing on a minimum rate of corporate tax, possibly under the auspices of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. …The economists also suggest establishing an intergovernmental tax body within the United Nations that would combat abusive tax practices.

The bottom line is that politicians and statist interest groups both want to extract more money from the productive sector of the economy.

And OECD bureaucrats have been assigned the task of crafting rules to undermine tax competition so that companies can’t escape those higher burdens.

Developing new rules is actually the easy part. The hard part is when the bureaucrats try to rationalize how higher tax rates and bigger government are somehow good for the global economy.

Particularly since economists who work at the OECD have written that lower tax rates and tax competition result in better economic performance.

P.S. To add insult to injury, American taxpayers provide the biggest share of the OECD’s budget. This means that our tax dollars are being used to generate policies that will result in higher tax burdens. Which is why I’ve argued, on a per-dollar-spent basis, that subsidies to the OECD are the most destructively wasteful part of the federal budget.

P.P.S. And to add insult upon insult, OECD bureaucrats get tax-free salaries, so they are insulated from the negative effects of policies they’re trying to impose on the rest of the world.