As part of his ill-considered credentialing-to-compete initiative, President Obama wants to greatly increase both the size and availablity of Pell Grants. Under his proposed FY 2011 budget, the total pot of Pell aid would rise from $28.2 billion in 2009 to $34.8 billion in 2011; the maximum award would go from $5,350 to $5,710; and the number of students served would rise by around 1 million.

A critical question, of course, is whether increasing Pell will ultimately make college more affordable or self-defeatingly fuel further tuition inflation. The New York Times took that up in yesterday’s Room for Debate blog.

Economist Richard Vedder has long educated people about the inflationary effect of student aid, and does so again with great clarity. It’s higher-ed analyst Art Hauptman, however, whom I think best captures what likely occurs when Pell is combined with all the cheap loans and other aid furnished by Washington, states, and schools themselves:

The degree to which student aid affects what colleges and universities charge varies between the Pell Grant and student loans. The Pell Grant has not had much effect on tuition levels in part because the amount of the awards does not vary with where a student enrolls. Institutions cannot affect how much a student receives, and the institutions that charge the most enroll the fewest Pell Grant recipients.

By contrast…there are several good reasons to believe that student loans have been a factor in the rising cost of a college education. Tuition has increased by twice the inflation rate for the past three decades while annual loan volume has increased tenfold in constant dollars.

Unlike Pell Grants…colleges have some control over how much students borrow as loan amounts. Moreover, just as one couldn’t imagine house prices being as high as they now are if mortgage financing were not available, it is difficult to believe that colleges and universities could have increased their charges so rapidly over time without the ready availability of students’ ability to borrow.

[W]e should worry…that increases in Pell Grants may lead institutions to reduce the amount of discounts they would otherwise have provided to the recipients, who are from poor families, and move the aid these students would have received to others. This possibility…is supported by the data showing that public and private institutions are now more likely to provide more aid to more middle-income students than low-income students.

So what’s likely going on? Cheap federal loans — which are available to students of all income levels and vary according to a college’s price — are probably the main direct tuition inflator. More indirectly, Pell probably encourages schools to move other aid from poorer to wealthier students, enabling the latter to pay ever-higher “sticker” prices. In other words, student aid powers tuition inflation!

Which brings me to a quick comment about the submission from College Board economist Sandy Baum, who trots out the standard “declining state appropriations” to explain our college-price pain.

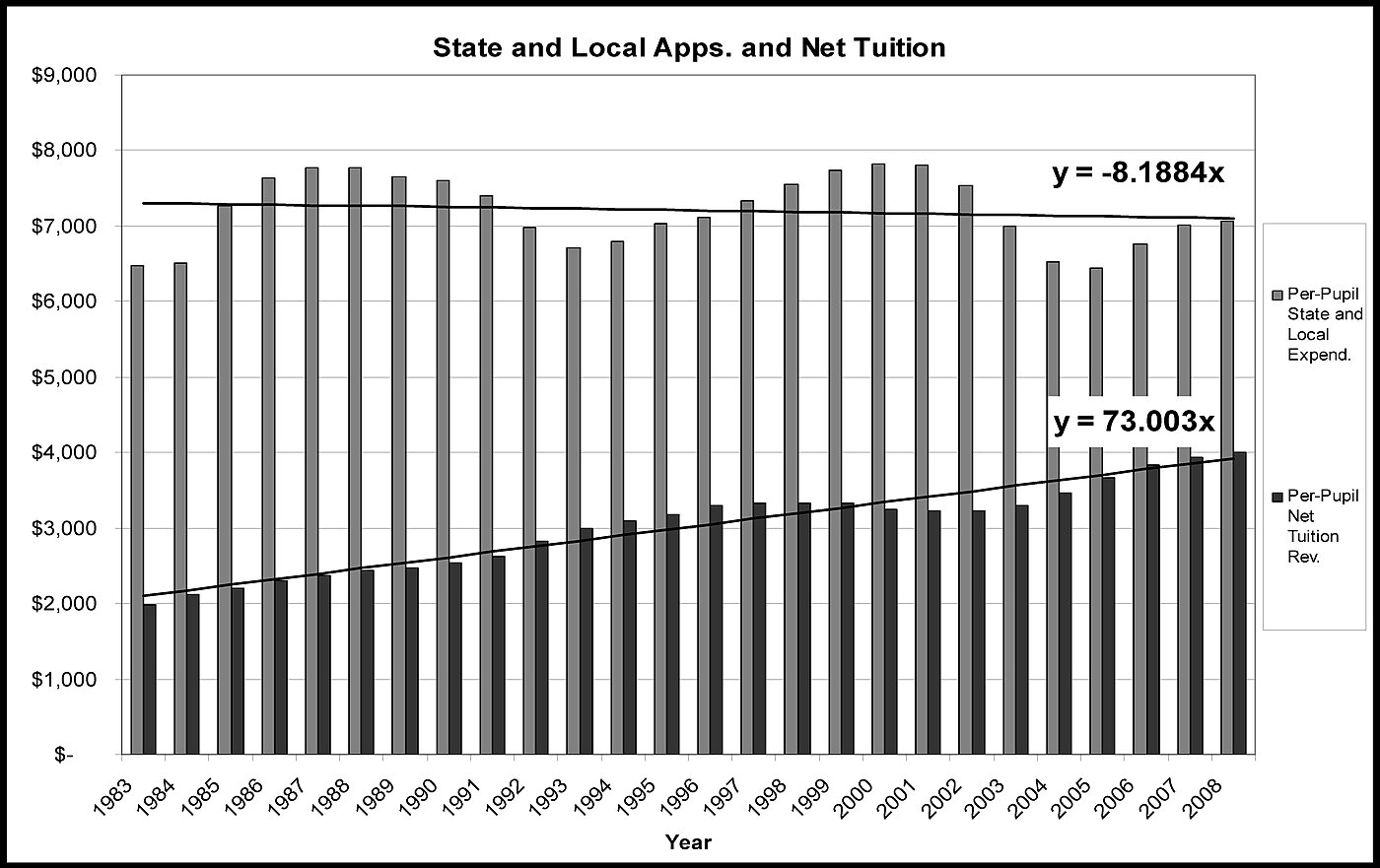

How many more times do I need to disprove this? Apparently, at least once more:

(Source: State Higher Education Executive Officers)

Public funding is a roller coaster and tuition revenue an incline. Over the last quarter century, per-pupil state and local funding for public colleges and universities went up and down, but dropped overall by a mere $8 per year. In contrast, public colleges’ per-pupil revenue from tuition (net of state and local student aid) rose more or less unabated, growing by about $73 per year.

This — as well as the fact that private colleges are also guilty of huge price inflation — clearly belies the notion that colleges raise prices because skinflinty governments make them. That might be part of the explanation, but an even bigger part is almost certainly that colleges raise prices because, thanks to ever-growing student aid, they can.