There was something almost otherworldly about President Obama’s big national security speech last Tuesday at the National Defense University in DC. At times, Obama seemed to position himself as the loyal opposition to his own administration—or just one of many concerned citizens who worry that perpetual war “will prove self-defeating, and alter our country in troubling ways.” A few examples from the speech:

Look at the current situation [at Gitmo], where we are force-feeding detainees who are being held on a hunger strike.… Is this who we are? Is that something our Founders foresaw? Is that the America we want to leave our children?

***

I’m troubled by the possibility that leak investigations may chill the investigative journalism that holds government accountable.

***

Unless we discipline our thinking, our definitions, our actions, we may be drawn into more wars we don’t need to fight.… this war, like all wars, must end.

***

The very precision of drone strikes and the necessary secrecy often involved in such actions can end up shielding our government from the public scrutiny that a troop deployment invites. It can also lead a President and his team to view drone strikes as a cure-all for terrorism.

“A president”? Anyone in particular? Who’s been president all these years, anyway?

Which administration is it whose “war on whistleblowers” features a record number of leak prosecutions and a disturbing pattern of spying on the press? Who was it that radically expanded drone strikes, and the theaters in which drones operate—and whose national security officials forsee at least another decade or more of remote-controlled warfare? Is Obama the guy who’s been tempted to view drone strikes as a panacea, or are we supposed to worry about shallower, less conscientious presidents to come? As Brookings’ Benjamin Wittes remarked, “To put it crassly, the president sought to rebuke his own administration for taking the positions it has—but also to make sure that it could continue to do so.”

In False Idol, my 2012 ebook on the Obama presidency, I wrote that “what Barack Obama has delivered is the same old Imperial Presidency with a dash or two of extra ‘Hope’ in the rhetoric.…The packaging is prettier, but the product is essentially the same.” Tuesday’s speech signals yet another rhetorical repackaging: going forward, it looks like we’ll get less “hope” and more handwringing. What practical difference that will make, if any, isn’t clear.

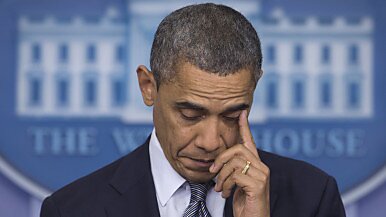

But as Ross Douthat notes, this public posture of reluctance and self-doubt charms many of Obama’s admirers: “If we have to have an imperial president, their attitude seems to be, better to have one who shows some ‘anguish over the difficult trade-offs that perpetual war poses to a free society.’ (as The New Yorker’s Jane Mayer put it on Friday).”

The Mayer piece Douthat quotes is remarkable in the degree to which it privileges style over substance. The title, “Obama’s Challenge to an Endless War,” is as surreal as the speech itself: the “endless war” the president’s supposedly challenging is the one he’s relentlessly expanded based on increasingly tenuous legal authority. If he wants to rein it in, what’s stopping him?

A little handwringing seems to go a long way for Mayer, the author of The Dark Side, a devastating critique of the Bush administration’s torture program. She begins by calling attention to “the contrast between Bush’s swagger and Obama’s anguish over the difficult trade-offs that perpetual war poses to a free society. It could scarcely be starker.” Bill “I feel your pain” Clinton got pretty far on a cheap politics of empathy, and perhaps Barack Obama’s learned from his example. Mayer seems mollified that this president feels the pain he’s causing.

The difference between Bush and Obama’s legal theories is stark as well, Mayer suggests: “Obama agonized over other limitations, too. Bush’s lawyers propounded the astonishingly radical theory that, as Commander-in-Chief, a President couldn’t be limited by domestic or international law,” but “Obama embraced both constitutional and international legal limits, at least in principle.”

“At least in principle” is doing a hell of a lot of work in that sentence. It’s true that Obama shies away from crass claims of inherent Article II prerogative; instead, he and his legal team prefer to acknowledge legal limits while interpreting them out of existence. There’s no better example of that than the 2011 Libyan War, wherein the administration did an end-run around Congress’s power to declare war by redefining the operation as a “kinetic military action.” When the War Powers Resolution’s 60-day clock ran out, Obama bypassed his own Office of Legal Counsel, securing a legal opinion from the dutiful Harold Koh, the State Department’s top lawyer, who argued that bombing Libya didn’t count as engaging in “hostilities” under the terms of the WPR. Koh, too, exhibits the sort of public soul-searching high-minded liberals swoon for: “How did I go from being a law professor to someone involved in killing?”—which must be a great comfort to those unjustly killed.

Obama’s NDU speech “was a paean to the theory of ‘just war,’” Mayer gushes, “it’s a sophisticated and nuanced moral theory, on which the law of conflict rests. Obama has openly grappled with the most difficult questions posed by the most serious thinkers in this area.” Lovely—but what difference does it make? If Bush’s favorite philosopher was Reinhold Niebuhr instead of Jesus, would Mayer have gone easier on him in The Dark Side?

There were a few kernels of substance amid the anguished posturing in Tuesday’s speech: Obama’s promise not to sign an expanded AUMF, lifting the moratorium on detainee transfers to Yemen. But in the main, what it means for the “endless war” Obama is allegedly challenging is anything but clear.