Unemployment benefits could continue up to 73 weeks until this year, thanks to “emergency” federal grants, but only in states with unemployment rates above 9 percent. That gave the long-term unemployed a perverse incentive to stay in high-unemployment states rather than move to places with more opportunities.

Before leaving the White House recently, former Presidential adviser Gene Sperling had been pushing Congress to reenact “emergency” benefits for the long-term unemployed. That was risky political advice for congressional Democrats, ironically, because it would significantly increase the unemployment rate before the November elections. That may explain why congressional bills only restore extended benefits through May or June.

Sperling argued in January that, “Most of the people are desperately looking for jobs. You know, our economy still has three people looking for every job (opening).” PolitiFact declared that statement true. But it is not true.

The “Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey” (JOLTS) from the Bureau of Labor Statistics does not begin to measure “every job (opening).” JOLTS asks 16,000 businesses how many new jobs they are actively advertising outside the firm. That is comparable to the Conference Board’s index of help wanted advertising, which found almost 5.2 million jobs advertised online in February.

With nearly 10.5 million unemployed, and 5.2 million jobs ads, one might conclude that our economy has two people looking for every job (opening)” rather than three. But that would also be false, because no estimate of advertised jobs can possibly gauge all available jobs.

Consider this: The latest JOLTS survey says “there were 4.0 million job openings in January,” but “there were 4.5 million hires in January.” If there were only 4.0 million job openings, how were 4.5 million hired? Because the estimated measure of “job openings” was ridiculously low. It always is.

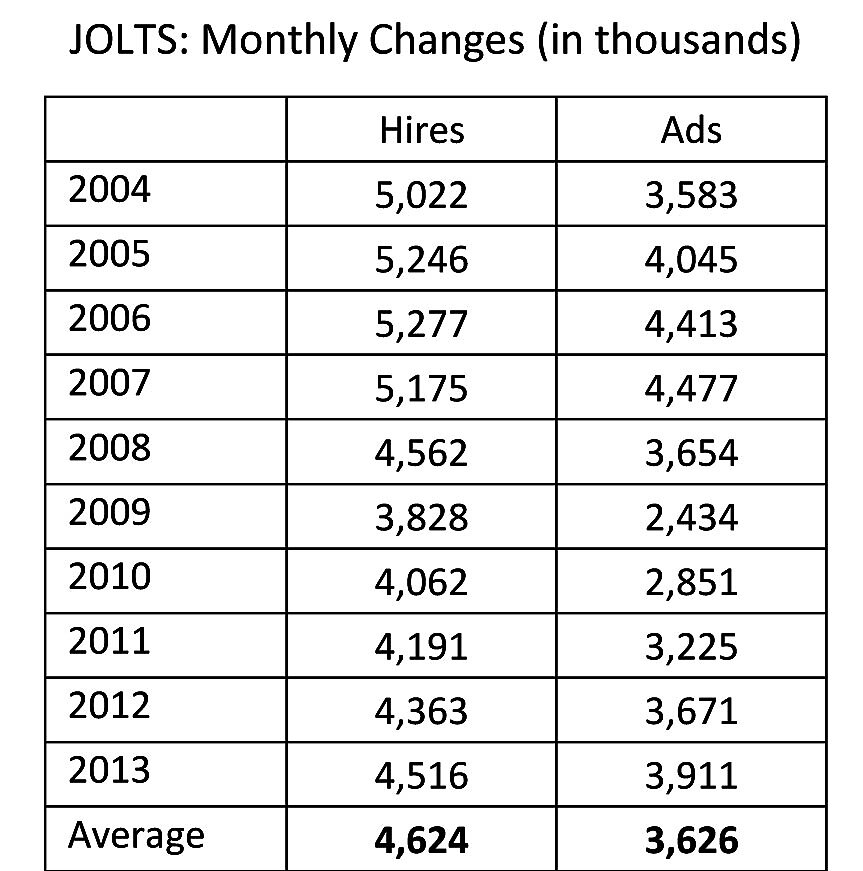

The Table shows that from 2004 to 2013 a million more people were hired every month (4.6 million a month) than the alleged number of “job openings” (3.6 million).

In years of high unemployment, such as 2004 and 2009, the gap between hires and ads reached 1.4 million – mainly because of reduced advertising rather than reduced hiring. The well-known cyclicality of help-wanted ads makes such ads a terrible measure of job opportunities. The number of advertised job openings always falls sharply when unemployment is high – because employers can fill most jobs without advertising. As Stanford economist Robert Hall explains, employers “see there are all kinds of highly qualified people out there they can hire easily, so they don’t need to do a lot of recruiting—people are pounding on the door.” This is one reason the number of help-wanted ads tells us little about the number of available jobs.

“Many jobs are never advertised,” explained a recent BLS Occupational Outlook Handbook; “People get them by talking to friends, family, neighbors, acquaintances, teachers, former coworkers, and others who know of an opening.” Note that because many jobs are never advertised they are also never counted as “job openings” by JOLTS.

The BLS Handbook adds that, “Directly contacting employers is one of the most successful means of job hunting.” Executive employment counselor Paul Bernard likewise warns against the “reactive approach” of looking for job ads; “Instead, take a proactive approach. Spend at least 75 percent of your time networking — online and in person — with people in fields you want to work in. These days, most good jobs come through personal networking.”

Yet jobs are acquired through the initiative of job seekers are not counted as job openings by JOLTS. New job openings within firms are excluded from this constricted concept of job opportunities. Even the common practice of rehiring previously laid-off employees when business picks up does not count as “job openings” in JOLTS because it requires only a letter or phone call, not advertising.

The JOLTS data on hiring proves that the JOLTS data on the number of help-wanted ads is useless as a measure of “job openings.” Paul Krugman, Gene Sperling, PolitiFact and others who repeatedly claim these ill-defined JOLTS estimates demonstrate that there are three job seekers for every available job are completely wrong.