In an interview with MSNBC last Thursday, new Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo spoke highly of the “national security” tariffs that President Trump placed on steel and aluminum imports in 2018 under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962. According to Secretary Raimondo, “[t]he data show that those tariffs have been effective.” As my colleague Simon Lester noted at the time, it’s not entirely clear whether Raimondo’s opinion was specific to China or the Section 232 tariffs more broadly, and she amplified the confusion by immediately following her remark with a note that the Biden administration is still reviewing the tariffs before deciding what to do with them. Nevertheless, there’s little to suggest that the tariffs have been “effective” — even by tariff supporters’ own benchmarks.

In a new paper, my colleague Inu Manak and I address the numerous legal problems raised by Section 232 — problems no one really noticed until Trump started abusing it with his metals tariffs and other actions — and explain why the law should be repealed or, at least, significantly reformed. I also detailed the main economic arguments against the Section 232 tariffs in a recent policy analysis on manufacturing and national security, showing how the tariffs served as “a powerful example of the perils of American security nationalism”:

Numerous studies have documented the tariffs’ high economic costs for U.S. consumers (particularly manufacturing firms). In particular, the tariffs caused higher steel prices that in turn hurt other U.S. manufacturers in terms of higher input costs, lower exports, and lost competitiveness at home and abroad; created an opaque, costly, and uncertain “exclusion” bureaucracy, under which more than 100,000 requests have been filed by U.S. manufacturers seeking relief; resulted in approximately 75,000 fewer manufacturing jobs than would have otherwise existed in the absence of the tariffs; depressed global demand for steel (thereby dampening prices); bred global market uncertainty, which hurt investment in manufacturing; and caused numerous U.S. trading partners to retaliate against American exporters.

At the same time, the steel tariffs were found to have a minimal impact on U.S. steelworker jobs and to do nothing to address global steel overcapacity—the primary long‐term driver of the U.S. steel industry’s weakened financial position in 2018. Given these and other market dynamics (e.g., steelmakers bringing back inefficient capacity to capture rents and subsequently flooding the U.S. market), industry stocks tanked in late 2018 and early 2019, and steel companies were actually laying off workers and curtailing investments by the end of 2019. In extending the tariffs to downstream “derivative” products in early 2020, the Trump administration tacitly admitted that the steel tariffs had not achieved their primary goal of increasing and stabilizing the industry’s capacity utilization. As one Los Angeles Times story put it, “Trump’s steel tariffs were supposed to save the industry. They made things worse.”

As has been widely documented here and elsewhere, the tariffs’ harms for U.S. consumers — particularly domestic manufacturers that consume steel and aluminum — are hardly in doubt, and skyrocketing prices are currently undermining the U.S. manufacturing recovery. However, Raimondo’s comments indicate that the Biden administration might not care about the tariffs’ obvious consumer harms when determining their efficacy. It’s thus worthwhile to expand upon that second paragraph above, which generally mirrors the very standards for success that tariff supporters used when the measures were first put in place. For example, the Trump administration identified three main goals in the Commerce Department’s Section 232 report on steel imports: (1) to boost domestic producers’ capacity utilization above 80% — the level reportedly “necessary to sustain adequate profitability and continued capital investment, research and development, and workforce enhancement” — for an extended duration; (2) by extension, to produce a “a healthy and competitive U.S. industry” in terms of employment, production, and investment; and (3) to reduce the “global excess capacity” — particularly in China — that was allegedly a driving force behind the steel industry’s recent troubles.

In each case, data through the start of 2020 (when the pandemic began) show that the steel tariffs provided the U.S. industry with a short-term “sugar rush” but did little to produce a thriving domestic steel industry or curtail global overcapacity. In other words, the tariffs failed on supporters’ own terms.

First, the steel industry only briefly achieved that magical 80 percent capacity utilization target after the tariffs were imposed in March 2018. Instead, iron and steel producers’ average post-tariff capacity utilization was only slightly above pre-tariff levels and right about where it was before 2015:

Indeed, as noted above, the Trump administration itself admitted that the industry’s capacity utilization goal remained unmet when Trump decided to extend the Section 232 tariffs to downstream “derivative” products, blaming this failed objective on the utterly-foreseeable increase in derivatives imports (which, unlike their American competition, weren’t forced to consume tariff-affected steel):

The Secretary has informed me that domestic steel producers’ capacity utilization has not stabilized for an extended period of time at or above the 80 percent capacity utilization level identified in his report as necessary to remove the threatened impairment of the national security. Stabilizing at that level is important to provide the industry with a reasonable expectation that market conditions will prevail long enough to justify the investment necessary to ramp up production to a sustainable and profitable level.

Next, data on steel industry employment, industrial production, and investment (capital expenditures) show that these metrics did improve a bit following the tariffs’ imposition in March 2018, but that these trends were already underway pre-tariffs and the gains soon began to fade in mid-2019, leaving the industry no better off in early 2020 than it was in the early to mid-2010s (right before the oil-price-induced manufacturing “mini-recession” in the United States began in mid-2014):

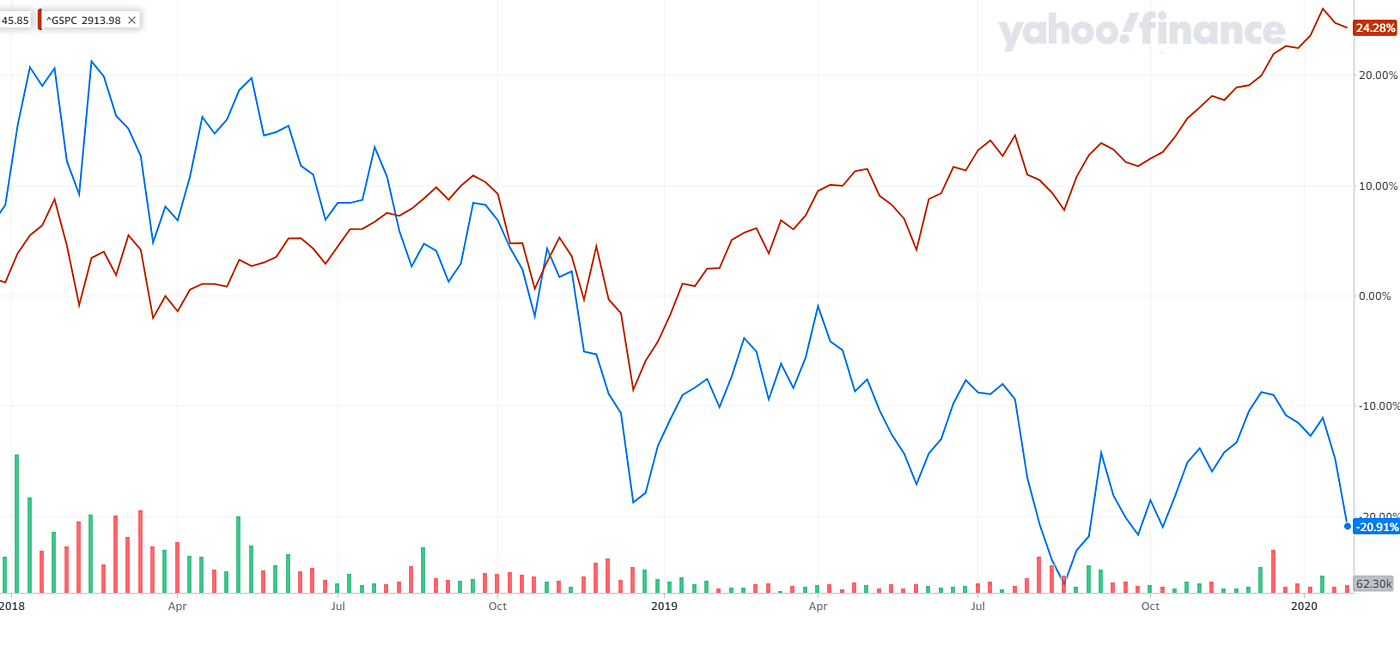

Based on this performance and the industry’s related financials, steel stocks — as shown below using an ETF that aggregates domestic steel company shares — continued their slide through the end of 2019, even as the S&P increased significantly:

Big names like U.S. Steel did far worse (resulting in one of the funnier financial TV segments from tariff supporter Jim Cramer).

Finally, the Section 232 tariffs have done absolutely nothing to reduce excess global steel capacity. In fact, Chinese production — in nominal terms and as a share of global production — actually increased between 2018 and 2020:

Thus, even if Secretary Raimondo was speaking about only the Section 232 tariffs on Chinese steel, they still haven’t been effective — an unsurprising conclusion, given that China was not even a top-10 import source for steel when the Section 232 tariffs were being considered.

Overall, none of the data above definitively support Raimondo’s conclusion last week about the steel tariffs’ efficacy. Hopefully she’ll embrace this reality once the Biden administration completes their review.