In the first presidential debate, Donald Trump said, “We have to stop our companies from leaving the United States and, with it, firing all of their people.… They’re going to Mexico. So many hundreds and hundreds of companies are doing this.” He later added, “The companies are leaving. I could name, I mean, there are thousands of them. They’re leaving, and they’re leaving in bigger numbers than ever.” But Trump didn’t name thousands. He named two: Ford and Carrier.

U.S. companies commonly grow by expanding overseas, often to meet local demand (e.g., McDonald’s and Uber) rather than to export back to the United States.

The amount invested is recorded as Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) abroad.

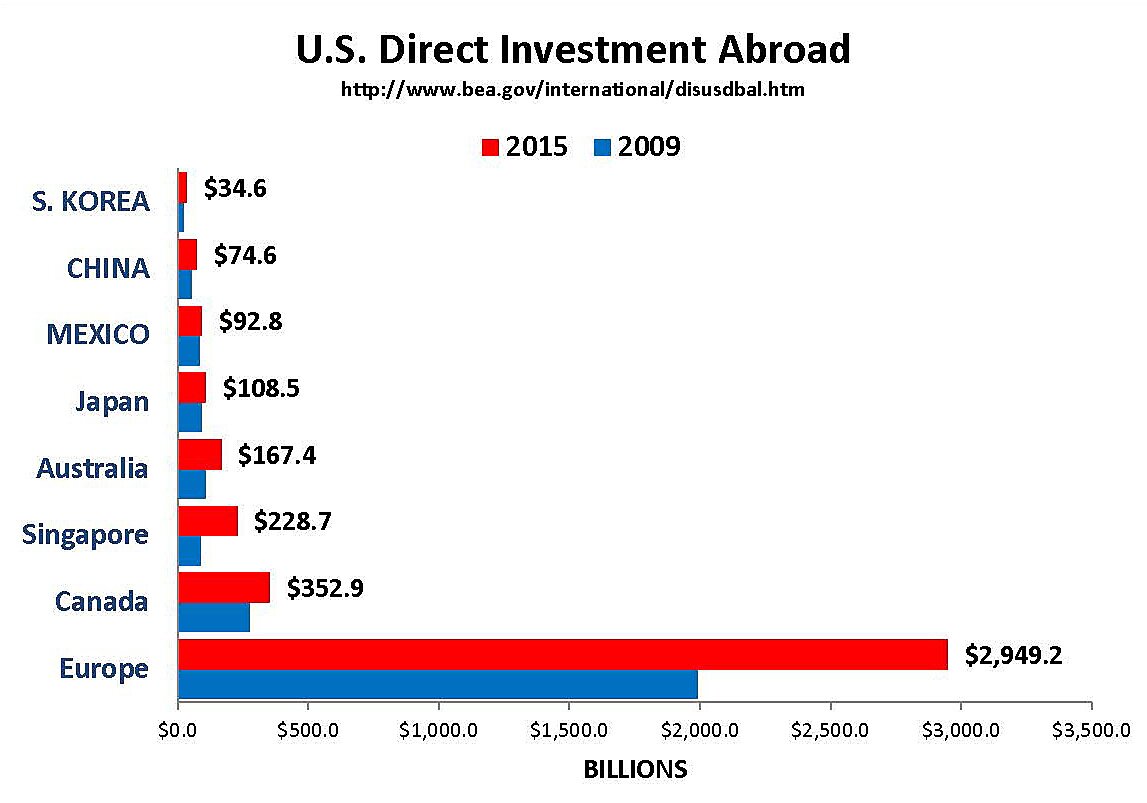

The graph shows the United States’ total direct investments in select countries for 2009 and 2015, valued at historic cost.

Contrary to Mr. Trump’s excited rhetoric, there has been very little FDI in Mexico, and such investments did not increase significantly from 2009 to 2015. In fact, China is now suffering a capital outflow, with a quarter of U.S. companies reportedly moving out.

U.S. firms mainly invest in their subsidiaries in Europe and Canada, and do so largely to service those markets more quickly with lower shipping costs. The U.S. runs a large trade deficit with Europe, second only to China, but that is a symptom of Europe’s economic weakness rather than strength. Stagnant economies neither need nor can afford many imports.

U.S. direct investment in Australia and Singapore increased significantly from 2009 to 2015. Far from being a threat, however, the U.S. runs sizable trade surpluses with both countries (and with Canada and Hong Kong), and has a Free Trade Agreement with Singapore.