In response to the crisis, federal policymakers have passed a series of aid packages providing hundreds of billions of dollars to state and local governments. Legislation, here and here, has provided $150 billion in flexible aid to the states plus more than $280 billion in other state and local aid for health care, education, housing, transit, food stamps, and other programs.

Congress and the administration are working on yet another bailout package. The House plan includes $1.1 trillion further aid to the states, while the Senate plan includes $105 billion for schools and colleges.

Federal aid to the states is harmful for many reasons. When tax revenues fall during recessions, state governments should tap their rainy day funds, cut low-value programs, freeze salaries, furlough workers, postpone new initiatives, and sell assets. The federal government can help by repealing rules that block the states from cutting spending on activities that receive federal money. Millions of American businesses are tightening their belts, so why not governments? Today’s lean budget climate is an opportunity to improve efficiencies in state and local agencies.

Even if some crisis aid to the states made sense, further aid would be too much. The aid already passed would mainly cover budget gaps if states were allowed maximum flexibility with the funds.

During the last recession, state tax revenues fell 10 percent from the 2008 peak and then began bouncing back. Recent projections suggest a decline this recession of no more than that. Tax Foundation surveyed current forecasts for a dozen states, and found that tax revenues are expected to fall about 4 percent in fiscal 2020 and 7 percent in fiscal 2021 from the fiscal 2019 peak. Tax Policy Center recently surveyed 27 states and found similar estimated declines, as did a recent study by economists Christos Makridris and Robert McNab. The budget gaps were larger when compared to a no-recession baseline of rising revenues.

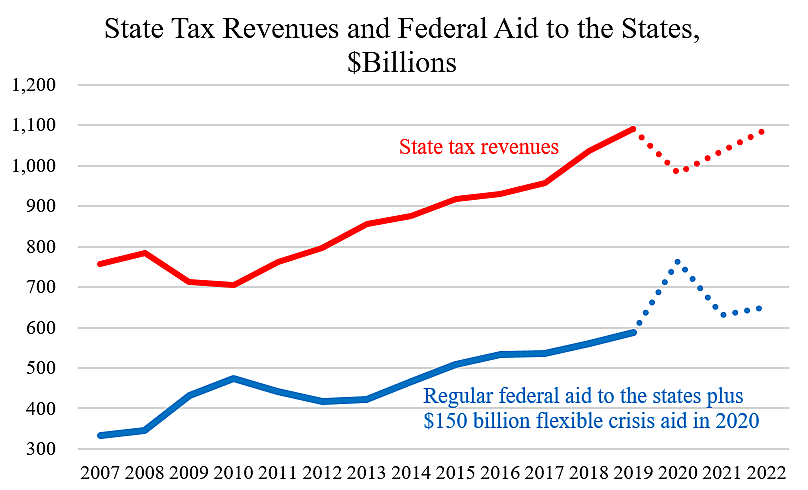

In the chart, the red line is Census data showing state tax revenues rising for a decade and peaking at $1.09 trillion in calendar 2019. Then the red dashed line assumes a 10 percent drop in 2020 and recovery in 2021 and 2022. Tax revenues would be down $109 billion in 2020 and $55 billion in 2021 compared to the 2019 level, for a two-year loss of $164 billion. The losses would be somewhat larger measured against a no-recession growth baseline. But either way, the aid handed out already would mainly fill state budget gaps if states were allowed to use the money flexibly.

The blue line in the chart shows total federal aid to state governments. The projection, 2020 to 2022, is based on regular aid growing per the pre-virus federal budget, plus the $150 billion in flexible crisis aid already provided. The media has focused on how much state tax revenues might fall, but even if the federal government provided no crisis aid, the large part of state budgets funded by federal dollars would chug along with steady increases.

Lastly, note that while state-level tax revenues may fall 10 percent this year, local government tax revenues may not fall much, if at all. During the last recession, overall local tax revenues were flat for a while and then began rising again.