Yesterday the New York attorney general reached a deal with the company Uber to cap its “surge” pricing during emergencies. The company, which uses an app to summon cars via a user’s smartphone, uses an algorithm that increases prices during periods of high demand, including emergencies and bad weather, to encourage more of its drivers to work. The agreement was reached in accordance with the City of New York’s law against price gouging, passed in 1979.

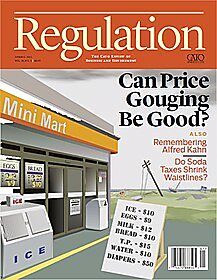

Was the agreement a good idea? In the cover story of the Spring 2011 issue of Regulation, Texas Tech researcher Michael Giberson examines the role of high prices and the resistance to them during emergencies.

Many people object to high prices during emergencies. The use of high prices by Uber after Hurricane Sandy prompted a Time writer to describe Uber’s pricing as “economically sound, ethically dubious.” Michael Sandel, professor of government at Harvard, is quoted in the Regulation article saying “A society in which people exploit their neighbors for financial gain in times of crisis is not a good society.… By punishing greedy behavior rather than rewarding it, society affirms the civic virtue of shared sacrifice for the common good.”

In response, Giberson argues “If it is admitted that giving merchants the freedom to pick their own prices does a better job than alternative ways of getting goods and services to where they are needed, then interference with that pricing freedom … harms precisely those persons who have been already harmed by the disaster, a result that suggests neither shared sacrifice nor promotion of a common good.” In addition, he argues it is unfair to “place a particularized obligation to sacrifice on a discrete segment of society, namely merchants. Addressing the particular hardships faced by the poor during emergencies is a task better left to government agencies or charities.”

Price gouging laws are an attempt to deny the economic realities of emergency situations. Price gouging laws reduce the incentives to provide needed goods and services in areas affected by emergencies and disasters. The cap on Uber’s surge pricing may make its customers happy now, but they may not be so happy when they wait hours for an Uber during the next blizzard, thunder storm, or other disaster. The writer concluded that “Price gouging might, at least in theory, help shrink lines and reduce shortages. But I think most people would rather wait in line than have someone make a windfall profit off their desperation.” With this agreement we will conduct the experiment to test his theory.

For more on Uber, see the recent blog posts by Cato’s Matthew Feeney and this article from the Summer 2013 issue of Regulation.