Global Science Report is a feature from the Center for the Study of Science, where we highlight one or two important new items in the scientific literature or the popular media. For broader and more technical perspectives, consult our monthly “Current Wisdom.”

The United Nation’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) seems more intent on maintaining the crumbling “consensus” on anthropogenic global warming than on following climate science to its logical conclusion—a conclusion that increasingly suggests that human greenhouse gas emissions are less important in driving climate change than commonly held.

This fact is obvious from the embarrassing lack of internal inconsistency contained in the leaked versions of the IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report. The Summary for Policymakers, a succinct and brief document supposedly encapsulating what is in the entire 3,000-page report is supposed to be approved by closing time on Friday, at a meeting currently taking place in Stockholm.

In no place will this internal inconsistency be more obvious than in how the IPCC deals with the discrepancy between the observed effectiveness of greenhouse gases in warming the earth and this effectiveness calculated by the climate models that the IPCC uses to project future climate change.

The warming effectiveness is known as the “climate sensitivity” and is the key parameter in how much the earth’s surface temperature rise as a result of the increasing atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. Most all climate impacts are related to the climate sensitivity—the lower the climate sensitivity, the fewer the impacts.

One problem. Climate scientists don’t know what the value of the climate sensitivity really is.

Not because the calculation is complicated—just take how much the global average temperature has changed over some longish time period (a couple of decades or longer) and divide by much energy was used to force that change.

What greenhouse gases, like carbon dioxide, do is to direct a skosh of radiation back down towards the surface rather than letting it escape out to space. The amount is small—think of evenly-spaced (every 3 feet or so) four-watt lightbulbs held above the surface. (If holding evenly spaced flashlights over the surface will take, say, forever to melt Antarctica, you’re thinking correctly!)

In fact, a reasonable value for the average energy change by late this century is about those four watts. “About” ought to be in italics because we really don’t know how much cooling is caused by other emissions, like particulate aerosols that go up the smokestack along with the carbon dioxide. And, for that matter, there are still some problems even knowing how much temperature has really changed because of differences that accrue depending upon how you measure and analyze it.

But the IPCC does provide estimates of these two values—temperature change and energy change—over the past century or so.

In its Fourth Assessment Report (AR4) (published in 2007), the IPCC reported that from 1901–2005, the global average surface temperature increased by 0.78°C. It also reported that the radiative forcing had increased by 1.6 watts per square meter (W/m2) from human activity.

If we make the assumption that very little of the increase occurred prior to 1901, then we calculate the climate sensitivity as 0.78°C divided by 1.6 W/m2 which yields a value of 0.49°C/W/m2. In other words, over the past century, the global average surface temperature seems to increase at a rate of about half a degree Celsius for each additional W/m2 of added energy.

This is what is known as the “transient” climate sensitivity—“transient”, in that the entire climate system has not yet come into equilibrium with the added energy. The temperature rise at equilibrium (known, unsurprisingly, as the “equilibrium” climate sensitivity) is higher than the transient climate sensitivity (how much higher is uncertain).

A doubling of the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide has been calculated to increase the radiative forcing by 3.7 W/m2, our proverbial tiny flashlight. So, multiply 0.49°C/W/M2 by 3.7 W/m2 and you get, according to IPCC’s previous numbers, that a doubling of the atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration produces a global temperature rise of roughly about 1.8°C (at the time of doubling, i.e., in a transient sense).

Now let’s see what the new IPCC report has to say.

From a leaked draft of the IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report (AR5), the IPCC reports a global temperature rise of 0.89°C** from 1901–2012 and a total anthropogenic radiation change of 2.29 W/m2. The new forcing estimate comes about from a newer understanding of the role of aerosols as well as the additional radiative forcing from greenhouse gas emissions since 2005. Repeating the climate sensitivity calculation with these updated estimates, and we get 0.89°C divided by 2.29 W/m2 equals 0.39°C/W/m2. This value is 20 percent lower than the value calculated with the IPCC AR4 numbers, and leads to a 1.44°C temperature rise at the time of a doubling of atmospheric carbon dioxide, a weenie .05°C/decade between now and when (if?) carbon dioxide doubles around 2075.

In other words, the latest observations reported by the IPCC proves that the climate seems to be less sensitive to changes in the greenhouse gas increases than the previous IPCC report indicated.

OK. This is well and good; now the IPCC’s new estimates are reflecting the latest science.

Unfortunately, the IPCC’s climate models are not.

If we examine the climate models chosen by the IPCC to make their projections of future climate change resulting from human greenhouse gas (and particulate) emissions, we find that instead of using models with a 20 percent lower transient climate sensitivity, the transient sensitivity of the models used by the IPCC is the same in the AR5 as in the AR4.

This has two serious implications.

First is that the climate models using by the IPCC are running behind the latest science, and secondly, and quite significantly, the climate models used by the IPCC produce too much warming for a given rise in atmospheric carbon dioxide levels. This means the climate model projections, which make up the meat of the IPCC Assessment Report (and upon which policy decisions the world around are based), are substantially overheating.

The IPCC implicitly admits this fact through its own numbers.

Now, if only they would admit this explicitly. Then we’d be getting somewhere. But, while they may pay small lip service noting things might not be all right, don’t hold your breath waiting for the IPCC to say “we goofed.”

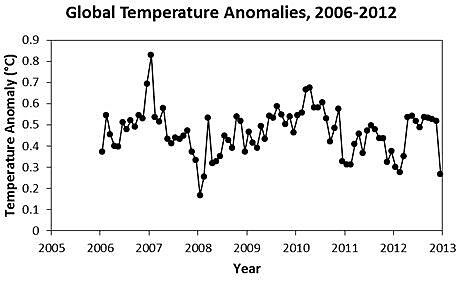

** Astute readers may wonder how this can be true, given the fact that everyone knows that there hasn’t been any warming since 2005. See for yourself in the East Anglia monthly climate history, the one scientists like best:

Through a quirk of statistics, the lack of warming observed since the IPCC’s Fourth Assessment Report has added about one-tenth of a degree to the overall global warming since 1900. Go figger!