Last week and this morning the results of two major international exams came out: the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) and the Program in International Student Assessment (PISA), respectively. Together, they offer a mixed bag of overall mediocre news for the United States.

On TIMSS—an exam that tends to use “traditional” questions such as directly multiplying two numbers—American students saw 4th grade math scores dip a bit between 2011 and 2015, 8th grade math scores rise a statistically significant amount, and 4th and 8th grade science scores rise slightly. We also placed pretty high compared to other countries, though we finished behind Kazakhstan on all tests. On the whole, that’s decent news (Kazakhstan notwithstanding).

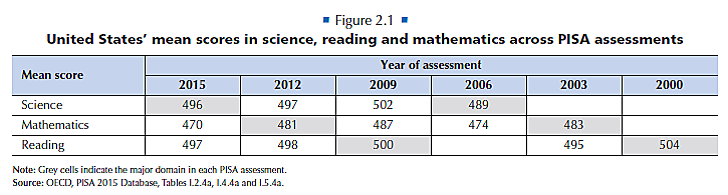

PISA would probably be best characterized the opposite way: bad news. Scores on the exam—which is more focused on solving “real world” problems, akin to multi-step word problems, and is only for 15-year-olds—were all down. Science, math, and reading, as you can see below, all dropped. And our placement among other participating countries? Well below average for advanced countries in math, slightly above in science and reading.

Taking PISA and TIMSS together, the news isn’t great, especially considering that we spend more on K‑12 education than almost any other country in the world.

That said, these scores only tell us so much, and it is impossible to definitively place blame or credit for them on any particular policy: school choice, Common Core, bilingual education, etc. It will be interesting to see, though, how groups like the Collaborative for Student Success will handle PISA. The Collaborative recently argued that adopting “high standards”—read: the Common Core—is clearly working because state test scores have gone up in many Core states. But it is quite possible that scores in Core states have risen largely because those states have adjusted to the Core, not because students are better educated. The target may have moved to the left, or even down, but scores will lag until sights are adjusted. Tests like PISA can serve as something of a check against using one exam to proclaim policy success.

Speaking of poorly grounded proclamations, the darling of progressive educators, Finland, continues to sink after its heady days atop the rankings about a decade ago. Its PISA science, math, and reading scores have all dropped since the early-to-mid 2000s. Meanwhile, the Finns ranked below the U.S. in 4th grade math on the most recent TIMSS, but above us in 4th grade science.

How about another country with somewhat mythical status: China. In the last two PISA iterations only students in elite Shanghai participated, and they scored very well. Alas, many commentators spoke as if atypical Shanghai represented all of China. This time around three other provinces participated, and scores plummeted.

What does all this tell us? First, that nothing clearly dramatic has happened in American education over the last few years, at least as reflected in scores on two international tests. That makes it especially hard to declare any particular policy proven good or bad, though the temptation to seize on test scores and make sweeping declarations is powerful. The scores also furnish a highly cautionary tale about picking the top-placing, country du jour—looking at you now, Kazakhstan!—and obsessing over what it has done and how we can do the same thing. It may not be so magical after all.

These tests tell us something. But what it is—and is not—can be tough to figure out. All we can say with some certainty is that the latest international exams, taken together, suggest mediocre American performance, especially for the money we spend.