(This is the second installment of a three-part essay. The first part is here.)

Big Engines that Couldn’t

Although Hoover’s Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) was “more largely a banker’s loan bank than anything else” (Ebersole 1933, 477), financial institutions were never the only firms eligible for its support. Railroads were an important exception from the start, though they were so mainly because financial institutions, commercial banks, and insurance companies especially, were railroads’ main investors. Thanks to New York and other state regulatory authorities’ inclusion of many railroad bonds among permissible investments for the banks and insurance companies they regulated, by 1932 those bonds made up 16 and 23 percent, respectively, of bank and insurance company assets (Mason and Schiffman 2002, 3).

Until 1929, railroad bonds had a good reputation: some lines had paid dividends without fail for generations. Hence their bonds’ AAA ratings. But the depression hit railroads hard. Between 1929 and 1933, their operating revenues were cut in half, while their fixed charges, including the interest they owed on their debts, stayed roughly the same. Even railroads that had been paying dividends continuously for generations were forced to stop doing so, causing their bonds to be downgraded. The RFC’s loans to railroads were supposed to help the financial industry by preventing railroads from defaulting on their debts, while sometimes helping the railroads pay for repairs and new constructions and otherwise keep their workers employed.

By the end of 1932, when financial institutions held 45 percent of the RFC’s outstanding loans, railroads were next in line with 21 percent (Ebersole 1933, 477). Unlike the RFC’s loans to banks, its loans to railroads were publicized from the start, because the Interstate Commerce Commission also had to sign off on them, and its policy was to report every loan it approved. Because it was mainly “Class I” railroads, with annual operating revenues of over $1 million, whose securities were on state regulators’ approved lists, most RFC railroad support went to them, with $280 million of a total of $350 million going to just 15 large lines. Over the course of its entire life, the RFC authorized 248 loans, totaling more than $1 billion, to 89 different railroads.

Whether they went to big railroads or smaller ones, the RFC’s railroad loans were generally earmarked for paying those railroads’ other creditors, with just a fifth being designated for upkeep and new construction. The fact that large investment houses were among the railroad creditors whose loans the RFC helped repay gave it still more bad publicity. One of its very first railroad loans, for example, helped the Missouri Pacific to repay a $5.75 million loan to J.P. Morgan and Company. The fact that the Missouri Pacific went bankrupt just over a year later didn’t make the loan it got smell any better.

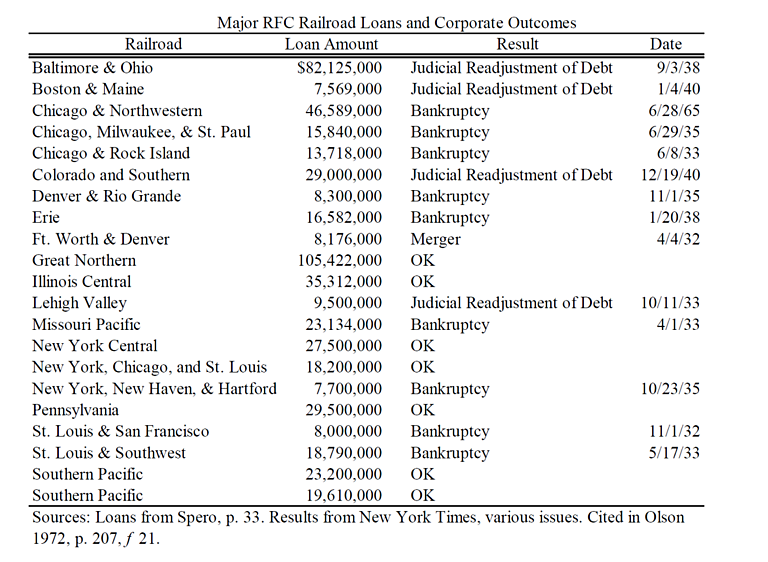

Yet apart from the Morgan connection, the Missouri Pacific case was to prove typical: during the Hoover years, two-thirds of the fifteen Class 1 railroads that received most of the RFC’s help ended up either going under or surviving only after having the courts intervene to adjust their debts (Olson 1982, 23; 97). Between Hoover’s departure and 1939, when the railroad lending program was wound-up after having lent a grand total of $802 million, twenty-five more Class 1 railroads that it helped suffered the same fate (Schiffman 2003, 806). The table below, reproduced from Mason (2000), shows the fates of a score of the RFC’s major railroad loan recipients. Evidently, however much it may have helped their creditors, the RFC’s largess alone wasn’t generally enough to save the railroads themselves.

The simple truth was that railroads’ woes weren’t just cyclical. Their losses also reflected the growing importance of newer forms of transportation. In October 1932, a group of major universities and insurance companies, all of which were saddled with lots of railroad debt, established a National Transportation Committee, with ex-president Calvin Coolidge as its head, to look into the railroad situation. In its February 1933 report, The American Transportation Problem, the committee concluded that, instead of just being victims of the depression, the railroads were facing “stiff, permanent competition from the [sic] airlines, automobiles, and trucks,” from which nothing short of “massive consolidation” could rescue them (Olson 1982, pp. 99–100).

So more credit was no real solution. But that’s not all. A recent, careful study (Daglish and Moore 2018) finds that the first announcement of a railroad’s first RFC loan tended to raise the spread between the yield on its bonds and that of Treasury securities by about 55 basis points, presumably because the loan was regarded by the public as a sign that its recipient was in trouble, and that in the long run, RFC assistance tended to lower railroads’ bond prices even more. So, instead of helping financial institutions with substantial railroad investments stay solvent, RFC support for railroads may have done just the opposite.

Nor does that support appear to have done the railroads themselves much good. On the contrary: most experts believe that RFC loans actually harmed them, by allowing them to delay both their bankruptcy and the reorganization of which many were in desperate need (Olson 98–99; Spero 1939). Because avoiding bankruptcy meant having to continue paying all their creditors, despite fallen revenues, roads that chose that option also tended to skimp on repairs and maintenance (Ebersole 1933, 486–7). For brief downturns, the strategy made sense. During the Great Depression, it became a recipe for railroad suicide. And because RFC loans allowed railroads that got them to stave off bankruptcy longer, they tended to make them that much less viable once they filed for it.

Bankruptcy itself did not, on the other hand, force railroads to shut down: instead of being liquidated, railroads were usually kept running by their receivers while shareholders made plans for their reorganization. Those plans typically emphasized rehabilitating the railroad’s neglected rights of way and equipment (Spero 1939; Mason and Schiffman 2002, 7). Jesse Jones put it pithily: “A bankrupt railroad cannot cut bait,” he says (1951, 107); “It has to keep on fishing.” And because they’re relieved of the obligation to pay the fixed charges on their securities, bankrupt railroads “are often able to keep their properties in better shape than those which remain out of receivership” (ibid., 108). For this very reason, one ought to take Jones’s claim that RFC railroad loans “created tens of thousands of jobs” (ibid., 106) with a pinch of salt: according to Jones’s own understanding, those loans seem more likely to have reduced overall railroad employment.

And that, according to several relatively recent studies, is just what the loans did. Surveying the whole 1929–1940 period, Daniel Schiffman (2003) finds that, once they went bankrupt, large railroads (which received 96.7 percent of the RFC’s railroad credits) tended to devote considerably more resources to maintaining their equipment and rights of way, and to keeping their workers employed, than they did while avoiding it by taking RFC loans. This was especially so, Schiffman says, during the crucial years 1930 through 1933. “[H]ad all large firms been bankrupt over that period,” Schiffman says (ibid., 820), “the additional maintenance spending would have boosted GDP by an average of 0.199 percent a year, and employment would have increased by an average of 0.125 percent per year.” He adds that his findings leave out multiplier effects. The lesson, Schiffman (ibid., 822) concludes, is “that governments should allow distressed firms to go bankrupt, instead of providing bailouts that merely postpone the inevitable.[1]

Minding the Gap

The RFC’s support for railroads was just the first inkling of what was to be a steady expansion of its involvement in lending to non-financial enterprises. During the Hoover administration, the Emergency Relief and Construction Act extended its remit to include lending to state and local governments for relief and public works and to various agricultural credit agencies. But that was nothing compared to the extent of the RFC’s reach under Jesse H. Jones’s leadership during the Roosevelt years. “The ‘new’ RFC,” Olson (1982, p. 43) observes, “would provide liquidity and capital to as broad business base as possible… . Slowly, almost imperceptibly as it poured billions of dollars into the economy, the RFC evolved into a major New Deal agency” which “[b]y the mid-1930s…was making loans to banks, savings banks, building and loan associations, credit unions, railroads, industrial banks, farmers, commercial businesses, federal land banks, production credit associations, farm cooperatives, mortgage loan companies, insurance companies, school districts, joint-stock land banks, federal intermediate credit banks, and livestock credit corporations.”

In this evolutionary process, no step was more controversial than the RFC’s decision to start lending to all sorts of ordinary businesses. Despite its other efforts, and officials’ attempts to cajole bankers into lending more, by late 1933 the volume of bank lending, and of commercial lending in particular, had hardly budged up from its level when the RFC was established. New Dealers feared that, by denying businesses the working capital they needed, bankers’ excessive caution threatened to undermine the efforts of their flagship recovery agency, the National Recovery Administration (Olson 1982, 137).

In response to such concerns, in September 1933 the RFC first offered to supply short-term funds to banks, mortgage loan companies, and other private lenders for up to six months at just 3 percent interest on the condition that they re-lend them to business firms for 5 percent or less. But the program was practically stillborn (Olson, pp. 139–40): by December the RFC had only lent $2 million under it. The bankers’ explained that, with prevailing money rates generally well below 5 percent—a fact they attributed to the limited demand for credit—the allowed spread just wasn’t big enough to cover their risks and still leave them with a profit. Some months before the RFC’s new initiative began, one of them had tried to warn the Senate Finance Committee that the government was erring by putting the credit-expansion cart before the purchasing power revival horse. “The administration,” he said, is “misinterpreting the real problem with the economy. … Banks were accumulating excess reserves…because there was so little consumer purchasing power in the economy. …Even hundreds of millions in RFC and Federal Reserve credit would not address the problem” (Olson p. 159).

But government officials weren’t buying it. Roosevelt even accused bankers of “hoping by remaining sullen to compel foreign exchange stabilization” (Olson, p. 138). Two 1934 studies offered grist for their mill. In the first, a survey of over 6000 firms nationwide conducted that July by the Bureau of the Census, 45 percent reported having trouble getting, with small firms having the most. The second, conducted by economists Charles O. Hardy and Jacob Viner, reviewed 1,788 loan refusals, and concluded that 374 good prospects were among them (Klemme 1939, 368–9). Such studies appeared to reveal a “credit gap,” that is, “a genuine unsatisfied demand for credit on the part of solvent borrowers” (ibid., 369). If the bankers wouldn’t fill it, even using cheap RFC credit, why not have the RFC itself do so? So, on June 19th, 1934, Congress gave the RFC permission to go into the commercial lending business.[2]

Alas, the performance of the RFC’s new Business Loan Division mainly served to prove that the bankers had been telling the truth all alone. Because Jessie Jones was determined to keep the RFC from lending to firms bankers themselves had good reasons to avoid, the RFC stuck to its own strict credit standards. Besides having to sport the Blue Eagle, firms to which it lent had to be financially solvent, and had to post adequate security. They were also supposed to show that they’d tried and failed to secure private-sector credit (Olson 1982, 163). Individual RFC loans were also limited to $500,000 and (more importantly) to 5 years maturity. Finally, the loans were made at prevailing market rates. When, some years later, the American Bankers Association sent out a survey asking businessmen whether the RFC’s credit standards were “appreciably less rigid than those of commercial banks,” 93 percent of those that responded said that they were either just as rigid, or even more rigid” (Kimmel 1939, 120). In short, whatever their other merits, the RFC’s commercial lending practices seemed tailor-made for testing whether the bankers were telling the truth about not overlooking good borrowers.

And the bankers passed that test with ease. By September the RFC had received fewer than 1200 business loan applications, and had approved only 100 of them, for a grand total of $8 million in loans. Two months later, an influential study commissioned by Henry Morgenthau and undertaken by C.O. Hardly and Jacob Viner, concluded—in case it wasn’t already obvious—that because the RFC’s lending policies hardly differed from those of most commercial banks, its business loan program had been “totally ineffective” (ibid., 168).

Not to be daunted, the RFC tried relaxing its lending conditions, particularly by gaining permission, at the end of June 1935, to lend for up to ten years and beyond its original $500,000 limit. But the changes made little difference. After climbing to 412 during the last quarter of 1934, the number of loans authorized by the Business Lending Division fell off rapidly so that, by the end of 1936, it had lent only $80 million to ordinary businesses, compared to $2 billion it lent to banks, and the $600 million it lent to railroads. During the 1938 downturn, it lowered its lending standards still further; yet by the close of that year it had still authorized only $384 million in loans to some 6,000 businesses, of which it disbursed only $157 million (Klemme, 370). “Even with liberalized regulations and more statutory authority,” James Stuart Olson (1982, 172) concludes, “the RFC’s business loan program never got off the ground”:

For more than three years [Olson writes], Jesse Jones had criticized and cajoled bankers, telling them to increase the volume of commercial and working capital loans or the country would stay mired in the depression indefinitely. But when the RFC started making those loans, Jones found himself agreeing with them: the number of applications was low and the credit worthiness of prospective borrowers left much to be desired (ibid., 177).

That the RFC’s Business Loan Division succeeded in making many loans at all was due to its eventual willingness to take risks no ordinary bank would have taken: most of its borrowers “were at, or under, the margin of creditworthiness when judged by the ordinary standards of commercial banks” (Saulnier, Halcro, and Jacoby 1958, 253–57). No wonder that, by February 1939, the division had racked up some $28 million in bad loans, meaning loans that had foreclosed, or were in the process of doing so, or ones that were in default (Klemme 1939, 373–74)—a loss rate well beyond what any commercial banker would have considered acceptable. It was, Jones admitted in his Seven Year Report to the President (1939, 10), “a substantially larger percentage of losses” than any of the RFC’s other divisions had incurred. And it was not helping the U.S. economy to recover.

Continue Reading The New Deal and Recovery:

- Intro

- Part 1: The Record

- Part 2: Inventing the New Deal

- Part 3: The Fiscal Stimulus Myth

- Part 4: FDR’s Fed

- Part 5: The Banking Crises

- Part 6: The National Banking Holiday

- Part 7: FDR and Gold

- Part 8: The NRA

- Part 8 (Supplement): The Brookings Report

- Part 9: The AAA

- Part 10: The Roosevelt Recession

- Part 11: The Roosevelt Recession, Continued

- Part 12: Fear Itself

- Part 13: Fear Itself, Continued

- Part 14: Fear Itself, Concluded

- Part 15: The Keynesian Myth

- Part 16: The Keynesian Myth, Continued

- Part 17: The Keynesian Myth, Concluded

- Part 18: The Recovery, So Far

- Part 19: War, and Peace

- Part 20: The Phantom Depression

- Part 20, Coda: The Fate of Rosie the Riveter

- Part 21: Happy Days

- Part 22: Postwar Monetary Policy

- Part 23: The Great Rapprochement

- Part 24: The RFC

- Part 25: The RFC, Continued

______________________________

[1] During the Roosevelt administration efforts were made, mostly on the urging of the ICC, to get the RFC to stop lending to doomed railroads. A June 16, 1933 amendment prohibited it from lending to railroads that clearly needed to be reorganized, while another, adopted in 1935, sought to limit its lending to railroads that “could demonstrate…their ability to survive a reasonably prolonged period of depression” (Mason 2000, 15–16). But because the RFC convinced the ICC to make exceptions to these rules, several railroads that received RFC support when they were nominally in effect still went bankrupt (ibid., 17).

[2] The so-called Industrial Advances Act also granted the Federal Reserve banks new powers to make direct loans to businesses by inserting a new section, 13b, into the Federal Reserve Act. These new powers were in addition to the 13(3) lending powers granted to the Fed in 1932, of which it made very little use during the depression. The Fed’s new industrial lending program was, if anything, even less successful than the RFC’s. Assessing it early in 1936, James C. Dolley (1936, 272) concluded that, because “[t]here was no widespread effective demand for industrial working capital credit which was not being accommodated by the commercial banks in 1934, and probably ever since the banking panic in March 1933,” it mainly succeeded in saddling the reserve banks with many bad loans. Selgin (2020) compares that failed Federal Reserve effort with the Fed’s attempt to lend directly to ordinary businesses during the COVID-19 crisis.