(This post continues my discussion of the “regime uncertainty” hypothesis, according to which the New Deal hampered recovery by causing businessmen to fear policy changes that might render their investments unprofitable.)

Insull’s Monstrosity

The 1935 Revenue Act wasn’t the only measure that had businessmen and investors shuddering that August. Less than a week after it became law, FDR signed the still-more controversial Public Utility Holding Company Act, granting the SEC the power to break up the nation’s utility holding companies.

On the eve of the Depression, Paul Mahoney explains, most U.S. electric and gas companies were directly controlled by trusts or holding companies. Groups of smaller utility holding companies were in turn controlled by a smaller number of larger holding companies, and so on for several layers. Three gigantic holding companies at the apex of this holding company “pyramid” ultimately controlled more than 80 percent of the nation’s power companies.

Until the Depression, the consolidation of the utilities industry awarded consumers and investors with falling electricity prices and robust returns. Even after the crash, utilities held up pretty well. Then, in June 1932, Insull Utility Investments, one of three holding companies at the top of the pyramid, failed, forcing many other holding companies to fail in turn. Some 600,000 utility shareholders faced huge losses.[1]

The Insull empire’s collapse turned Samuel Insull, its septuagenarian founder, into a symbol of the greed and corruption many blamed for the boom and bust. It also encouraged FDR, who had already crossed swords with utilities as New York’s governor, to make reforming them part of his New Deal. Roosevelt threw down the gauntlet during his September 21st Portland speech, assailing the “Insull monstrosity” and calling its business methods “wholly contrary to every sound public policy.”[2]

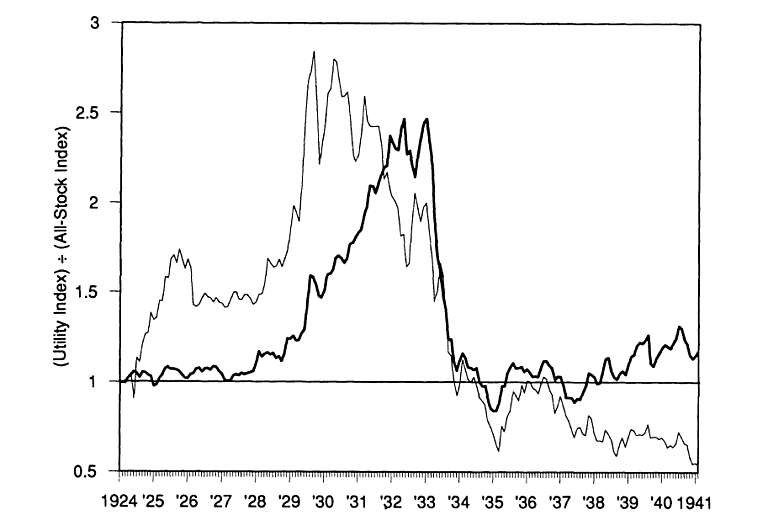

Roosevelt’s election left no doubt that a reform of the electric utility industry was coming. But no one knew just when, or what form it would take. Some New Dealers favored regulation; others wanted to ban utility holding company pyramiding, if not all utility holding companies. This uncertainty caused surviving utility share prices, which were still outperforming the market despite Insull’s downfall, to plummet, as can be seen in the chart below, from a 1992 article by William Emmons III.

Utility reform stayed on FDR’s back burner until July 1934, when he appointed a National Power Policy Committee to study the utility companies and propose legislation. The committee wouldn’t complete its report until late January, 1935. In the meantime, investors remained on edge, with many fearing the worst. In a January 19th column titled “Utility Baiting,” The Commercial and Financial Chronicle reported on what it called the “wholesale slaughter” of utility holding companies. “The attack of the Administration upon the utility industry,” it noted, “does not seem to abate with the passage of time.” Instead “the plans of the President to conduct a vigorous, and apparently an indiscriminate, attack upon utility holding companies [are] proceeding with dispatch.”

An Electric Shock

The administration finally introduced its bill on February 6, 1935, ending the suspense, but confirming investors’ worst fears. For its plan included what quickly became known as a “death sentence” provision, granting the SEC the power, not just to put a stop to pyramiding, but to force utility holding companies to disband altogether. That drastic step would expose those companies’ many shareholders to large fire-sale losses.[3] In less than a month, the New York Times reported, the bill had called forth “the greatest volume of criticism and objection evoked by any proposed legislation in recent years.” Considering the date, this was saying a lot!

But although the administration had made up its mind, the final outcome remained very much in doubt. Its bill now went on a six-month-long legislative roller-coaster ride, during which the death sentence appeared to die, was miraculously reborn, and was threatened with death once more. At last, in mid-August, a compromise was reached: the revised bill would ban pyramiding. But it would still allow individual holding companies to survive provided each controlled a geographically contiguous set of operating companies. At last, on August 26th, 1935, FDR signed the Public Utility Holding Company Act, better known as the Wheeler-Rayburn Act. Yet even that didn’t quite settle things. The industry at once fought back by filing a suit challenging the new law’s constitutionality, which was not finally settled until March 28th, 1938, when the Supreme Court ruled in the government’s favor.

Our concern isn’t with the Wheeler-Rayburn Act’s constitutionality, or its overall merits. It’s with the economic consequences of the fears that haunted investors and businessmen while the threat of draconian reform dangled over the utility industry like the sword of Damocles. In the famous open letter he published in the New York Times at the end of 1933, Keynes had reminded the President that he was “engaged in a double task, recovery and reform,” and that “for the first, speed and quick results are essential.” “On the other hand,” he went on to say,

even wise and necessary reform may, in some respects, impede and complicate recovery. For it will upset the confidence of the business world and weaken its existing motives to action before you have time to put other motives in their place.”

Whatever might be said in favor of FDR’s assault on utility conglomerates, it flew in the face of Keynes’s advice.

No Love Lost

Having dealt with the utilities, Congress adjourned. Soon after, FDR received a letter from Roy Howard, an influential newspaper editor and publisher who had supported his 1932 campaign. “Businessmen who once gave you sincere support,” the letter warned, “are now not merely hostile, they are frightened.” Howard went on to urge the President to “undo the damage that has been done by misinterpretation of the New Deal” by posting a public reply to his letter promising “a breathing spell to industry.”

To Howard’s surprise, and the business community’s immense relief, FDR’s reply, published in early September, didn’t just grant the requested breathing spell. It said that his legislative program “has now reached substantial completion.” New Deal experimentation had finally run its course. Or so it seemed.

And how the public breathed! Ray Moley (p. 318) later recalled its response, which “astonished” Roosevelt. “Thousands of letters and telegrams came in congratulating the President. Stock issues hit the highest level since September 1931 and the Gallup poll showed later a spectacular rise in Roosevelt’s popularity.” According to Gary Dean Best (pp. 110–111), “Businessmen, business writers, and business periodicals hailed the beginnings of the long-awaited recovery. Only a few skeptics warned that despite any boom that might occur, the foundations for a genuine recovery had not yet been laid.”

Alas, as some of those skeptics feared, the breathing spell turned out to be just that: an opportunity for businessmen to gulp some air before the next wave broke over them. Nor was that wave long in coming. No sooner did Congress reconvene, than FDR went on the offensive again. Instead of offering the usual, bland account of economic conditions, with suggestions for improving them, FDR made his 1936 State of the Union address the occasion for what The Nation called an anti-business diatribe. “We have returned the control of the Federal Government to the City of Washington,” Roosevelt said.

To be sure, in so doing, we have invited battle. We have earned the hatred of entrenched greed. The very nature of the problem that we faced made it necessary to drive some people from power and strictly to regulate others. I made that plain when I took the oath of office in March, 1933. I spoke of the practices of the unscrupulous money-changers who stood indicted in the court of public opinion. I spoke of the rulers of the exchanges of mankind’s goods, who failed through their own stubbornness and their own incompetence. I said that they had admitted their failure and had abdicated. … [B]ut now with the passing of danger they forget their damaging admissions and withdraw their abdication. They seek the restoration of their selfish power.

Roosevelt then deftly turned the tables on businessmen who complained that his policies undermined their confidence. “Their weapon,” he said,

is the weapon of fear. I have said, “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” That is as true today as it was in 1933. But such fear as they instill today is not a natural fear, a normal fear; it is a synthetic, manufactured, poisonous fear that is being spread subtly, expensively and cleverly by the same people who cried in those other days, “Save us, save us, lest we perish.”

I am confident that the Congress of the United States well understands the facts and is ready to wage unceasing warfare against those who seek a continuation of that spirit of fear.”

FDR’s verbal assaults on big business went on for the rest of that year, reaching a sort of apotheosis during his famous Madison Square Garden campaign speech that October. Comparing “business and financial monopoly” and other manifestations of “organized money” to an “organized mob,” he promised that they’d met their match. And he made no bones about having a personal score to settle. “They are unanimous in their hate of me,” he said. “And I welcome their hatred.”

Words, every child learns, aren’t sticks or stones. But to suppose that Roosevelt’s anti-business harangues couldn’t do any harm is to risk underestimating the part business confidence plays in sustaining private-market activity. What mattered, Schumpeter wrote (1939, p. 1046), was less that businessmen were threatened but that they felt threatened.

They realize that they are on trial before judges who have the verdict in their pocket beforehand, that an increasing part of public opinion is impervious to their point of view, and that any particular indictment will, if successfully met, at once be replaced with another.

“In a political and social environment which was infected with such hatreds and distrusts,” Kenneth Roose observed some years later (p. 224), “the risks and uncertainties of investment decision were seriously increased.” Moley (pp. 132–3) puts it more bluntly still. FDR’s “vague, veiled threats of punitive action,” he says, “tore the fragile texture of credit and confidence upon which the very existence of business depends.”

The Unkindest Cut

In the midst of this war of words, Congress passed the 1936 Revenue Act, including the notorious “undistributed profits tax.” That provision taxed firms’ retained net earnings (that is, those not paid out as dividends) at rates that rose with the share of retained to total earnings, with a maximum rate of 27 percent for a share of 60 percent or more. The administration hoped that, besides raising another $600 million in revenue, the new tax would stimulate spending by discouraging corporations from hoarding cash.

But to many, the new tax, the first word of which came in FDR’s supplemental March 3, 1936 budget message to Congress, was just another New Deal assault on business. “No other single measure, except possibly utility legislation, was so disapproved of by business” (Roose 1954, pp. 212–213). Writing in 1938, Willard Thorp, Director of Economic Research for Dun & Bradstreet, remarked that “with respect to no other legislative action of the last several years has business presented such a strong and unified front” (ibid., pp. 213–14, n16). Thanks to this concerted opposition, and despite FDR’s refusal to sign any tax bill that excluded it, the undistributed profits tax was omitted from the 1938 Revenue Act, and expired at the end of that year.

Rightly or wrongly, businessmen saw the undistributed profits tax as confirming the now widespread belief that the government was out to get them. As George Lent observes in his comprehensive 1948 assessment of the tax, “With the major exception of public utilities and railroads, American industry has expanded largely through the reinvestment of corporation earnings.” Consequently the undistributed profits tax “raised a fundamental issue over the proper direction and control of business investment and expansion” (pp. 111–12).

A Bark Worse Than Its Bite

How much did the undistributed tax really matter? According to Lent, its direct consequences “do not appear to have been so serious as its most violent critics have charged, or so desirable as its most ardent proponents have claimed.” The tax ended up raising only $145 million and $176 million in 1936 and 1937, respectively, with only 2.5 percent of firms paying the maximum 27 percent rate, and most others instead managing, through increased dividend payments or otherwise, to keep the surcharge at its lowest, 7 percent level.

Nor do the tax’s direct effects on investment seem to have been as severe as many feared they might be. Although it reduced retained earnings, to the extent that it did so by boosting dividends and other firm expenditures, the tax supplied others with means for purchasing more securities. And larger firms were able, Lent says (pp. 158 and 161), to make up for most of their loss of internal funds by selling securities or borrowing from banks. It was mainly small and medium-sized ones that found themselves placed “at a disadvantage in securing funds for growth” (ibid., p. 188).[4]

But while the undistributed profit tax may not have severely reduced businesses’ access to funds, it doesn’t follow that fears raised by it, together with its uncertain future, did not reduce their desire to invest. According to Kenneth Roose, by tending “to increase the uncertainty concerning the nature of the economic system of the future,” it did just that. “It would be a hardy investor indeed,” Ray Moley (p. 311) wrote, “who would venture his money in an enterprise that had no opportunity to acquire the very essentials of permanent corporate health.” It’s perhaps owing to such doubts, and not simply because they detested the undistributed profits tax, that in a survey of 3,000 Illinois manufacturers, 83 percent reported having “deferred or abandoned plans for plant expansion or rehabilitation” because of it (Lent, p. 132).

More recent research by Ellen McGrattan, involving a model in which uncertainty about future dividend tax rates plays a central part, lends support to Roose’s claim. “If, in addition to raising individual income tax rates,” McGrattan writes, “the government introduces a tax on the undistributed profits of corporations, as the U.S. government did in 1936, then investment is … negatively impacted. The introduction of such a tax would naturally affect the recovery in the second half of the 1930s.” In fact, McGrattan says, “tax rates on undistributed profits…led to [a] dramatic decline in investment.”

Packing it In

No survey, however brief, of confidence-shaking New Deal programs would be complete that failed to include the “court packing” plan originally hatched on Boxing Day, 1936. Still seething from the Supreme Court’s overturning of the NIRA and AAA, FDR had been looking for a way to bring it to heel, and was now convinced that his Attorney General had found it. The plan couldn’t have been simpler: the administration would author a bill to add up to six new justices to the bench, ostensibly for the sake of reducing the heavy burden being borne by the then-existing justices.

Alas, the plan also couldn’t have been more transparent. No sooner was the government’s plan unveiled, on February 5th, 1937, than its critics—including many Democrats—condemned it as an assault upon the Court’s independence. Although the administration pulled no punches in trying to push the measure through, it ultimately failed, thanks in part to a scathing Senate Judiciary Committee report on the bill that said it “should be so emphatically rejected that its parallel will never again be presented to the free representatives of the free people of America.”[5] One month later, Senate Majority Leader Joseph T. Robinson, who’d been leading the administration’s charge in the Senate, died of a heart attack. A week later the bill was sent back to committee, where the court-packing provision itself died.

The judicial implications of FDR’s court packing effort don’t concern us. But its effects on business confidence do. Although FDR himself never revealed what “kind of economic reform that his ‘reinvigorated court’ was supposed to approve” (Moley, p. 364), according to Gary Dean Best, his “determination to dominate the court convinced business and other critics that Roosevelt had in mind another sweeping program of business control akin to the NRA.” Considering the almost universal unpopularity of the original NRA, and the extent to which it impeded recovery, that would seem to have been a frightening prospect indeed.

***

So much for our parade of New Deal horribles, meaning actual or threatened policies that are supposed to have undermined businessmen’s confidence either directly or making them uncertain about the future business environment. Like all such parades, this one may convince you of the merits of the regime uncertainty hypothesis through its sheer vividness. But it shouldn’t: the true test of that hypothesis isn’t whether anecdotal evidence makes it seem convincing, but whether both theory and statistical evidence bear it out. I turn to consider such proof in the next installment of this series.

Continue Reading The New Deal and Recovery:

- Intro

- Part 1: The Record

- Part 2: Inventing the New Deal

- Part 3: The Fiscal Stimulus Myth

- Part 4: FDR’s Fed

- Part 5: The Banking Crises

- Part 6: The National Banking Holiday

- Part 7: FDR and Gold

- Part 8: The NRA

- Part 8 (Supplement): The Brookings Report

- Part 9: The AAA

- Part 10: The Roosevelt Recession

- Part 11: The Roosevelt Recession, Continued

- Part 12: Fear Itself

- Part 13: Fear Itself (Continued)

_____________________

[1] One estimate puts the ultimate cost to the public of those failures at $638 million, or just over 24 percent of the face value of the securities involved. But no such estimate could be made until 1946, when all the failed companies had been reorganized. Until then, much greater losses were anticipated.

[2] On October 4, 1932, a Chicago grand jury indicted Sam Insull and his brother, Martin, for embezzlement and larceny. Insull, who was in Paris at the time of the indictment, fled first to Greece and then to Istanbul to evade extradition, but was apprehended on a freighter bound from there to Egypt. He and 14 of his associates went on trial on October 2nd, 1934, the main charges against him being that he had “fraudulently schemed to induce investors nationwide to buy the common stock of Corporation Securities Company at inflated prices,” and that he’d used the mails to send circulars to those investors. During the trial, Floyd Thompson, the chief defense lawyer, argued that the government was making Insull a scapegoat for the depression itself:

Gentlemen, you have had a description here of an age in American history which we hope never will be repeated. We are trying that age. There is no proof here that anyone had any wrongful motive. There is proof that these men believed implicitly in the business venture in which they were engaged, and they poured their own fortunes and their own good names into it.

The jury apparently agreed: at midnight on November 24th, 1934, after deliberating for just 5 minutes, it found Insull and his co-defendants not guilty of all charges.

[3] As the previous chart shows, that’s exactly what happened. According to Paul Mahoney, the new law’s death sentence provision was regarded by traders “as detrimental to both the controlling companies at the top of the utility pyramids and to the controlled companies in the lower tiers of the pyramids.” For utilities that were already financially distressed, the “loss of a continuation option” was bound to mean collapsing share values. This outcome was an ironic answer to the harm Insull is supposed to have done to his own companies’ shareholders.

[4] According to research by Calomiris and Hubbard (1995), only about one-quarter of all firms issued bonds in 1936, with just 10 percent of those that did accounting for 90 percent of the bonds issued.

[5] No such luck, alas. Earlier this month, in the first such attempt since FDR’s, the Democrats introduced legislation to add four new justices to the Supreme Court.