“Under the New Deal, the US economy grew at rapid rates, even for an economy in recovery.” (Eric Rauchway, The Money Makers, p. 100.)

Before I start telling you what “the New Deal” did and didn’t do, I had better make clear what I mean by the phrase, if only to assure you that my meaning is perfectly conventional. Like Wikipedia, when I say “the New Deal,” I mean the “series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939.” I point this out because some claims made about the New Deal’s contribution to recovery refer to certain parts of it only, rather than to the whole thing.

Relief, Recovery, and Reform

Readers looking for a comprehensive list of New Deal undertakings are encouraged to consult that Wikipedia entry, for there were too many for me to list here, let alone describe in any detail. During its famous “first 100 days” alone, the Roosevelt administration passed 15 major pieces of legislation and created roughly as many new Federal agencies; and these early efforts were to be followed by many others. Although, as we’ll see, many of these efforts had Hoover-administration precedents, and some were merely repackaged versions of Hoover-era schemes, the scale and overall scope of New Deal undertakings was such as to constitute a sea-change in the federal government’s role—one that has endured ever since.

But not all of these New Deal efforts were aimed at promoting economic recovery. Instead, as any high-school American history text will tell you, the New Deal had three distinct aims—the “three R’s” of relief, recovery, and reform. It doesn’t follow that every New Deal effort can be neatly assigned to just one “R”: many can be said to have been intended to serve, if not to have served, multiple ends. Any relief program that meant more spending, for example, could also serve to promote recovery, particularly if it was financed by borrowing.

But programs that brought relief, as many New Deal programs did, didn’t necessarily promote recovery. FDR himself understood this. “Emergency relief under way and planned,” he wrote in Looking Forward (1933, p. 224) “will succeed only in the vital work of maintaining life. But it corrects nothing.” The same was true of New Deal programs whose chief aim was reform. Indeed, as we’ll see, some New Deal reforms undermined what might otherwise have been a far more successful New Deal recovery program.

As for New Deal policies and programs that had recovery among their chief aims, these were all supposed to help restore the general level of prices to its pre-depression level. Like many people at the time, FDR viewed the decline in prices since 1929 not just as a symptom but as a cause of the depression. As we’ll see, this reasoning was far from being altogether sound. Nevertheless, taken together with the Brain Trust’s aversion to “greenbackism” and various other populist proposals for money creation, it readily accounts for all of the New Deal’s otherwise diverse recovery gambits, including the abandonment of the gold standard; the RFC-financed gold-purchase program; the establishment of the Agricultural Adjustment and National Recovery Administrations (AAA and NRA); and the dollar’s eventual, official devaluation.

The Course of Unemployment

Did these and other New Deal programs succeed in pulling the U.S. economy out of the Great Depression? To begin to answer that question, we first need to examine the bare facts concerning the depression and recovery. Those terms refer, most obviously, to the sharp decline in output starting in 1929 and its eventual return at least to its pre-depression level, if not to a higher level consistent with some pre-depression trend. But they also refer to the equally-sharp post-1929 increase in unemployment and the subsequent return to what most consider “full” employment.

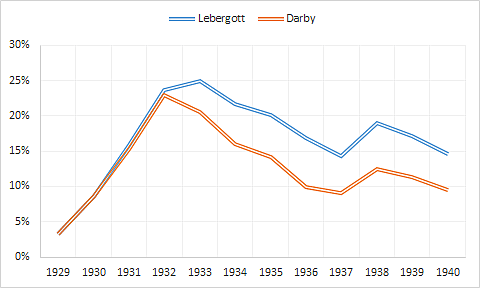

That the US economy suffered its most severe depression in the opening years of the 1930s is notorious. That it recovered rapidly for several years starting in mid-1933 is less well known, but no less indisputable. But the story of the Great Depression is far from a simple tale of depression followed by a speedy recovery. Consider the progress of unemployment, as seen in this chart snatched from Jim Rose’s blog:

Ignore the orange line for now (I’ll come to it): the blue one is the standard, BLS unemployment measure which, I maintain, is best for gauging the progress of the recovery. And that progress was neither steady nor ever close to complete. From 3.2 percent in 1929—which was by no means an exceptionally low rate by the standards of that decade—unemployment rose to a peak of just under 25 percent in 1933. By 1936 it had fallen to just below 17 percent. But then it rose again, to 19 percent, after which it fell to 14.6 percent. To put these figures in perspective, the peak unemployment rate during the severe but relatively short-lived 1920–21 recession, and the highest since the 1890s, was 11.7 percent. Even at its lowest level, the Great Depression unemployment rate was almost 3 percentage points higher.

Now, about that orange line. That shows a different measure of unemployment proposed some years ago in a 1976 JPE article by Michael Darby. What makes it different is that Darby counted all the persons working in New Deal work relief programs as “employed,” whereas the standard measure considers them unemployed. As you can see, although Darby’s numbers still don’t show unemployment dropping much below double-digits (the lowest level, for 1937, is 9.1 percent), they make the New Deal look a lot more successful than the standard numbers do.

Now, if all this were just a matter of classification, it wouldn’t signify much. After all, what we care about in gauging recovery isn’t simply whether people are working but whether the economy is capable of coming up with reasonably permanent jobs for them. But Darby’s position isn’t simply a matter of terminology: he claims that relief work served, not to give employment to workers who would otherwise have been unemployed, but to give better-paying or otherwise more attractive jobs to workers who could have found other jobs had they tried. According to that hypothesis, Darby’s numbers show the true pace of recovery.

But it’s a hard hypothesis to swallow. As Jonathan Kesselman and N.E. Savin note in their 1978 response to Darby, although it’s true that relief work was sometimes more appealing than private alternatives, it doesn’t follow that those alternatives were readily available. What’s more, they offer plenty of good reasons for thinking it wasn’t, starting with the most obvious, to wit: that millions of “Darby-unemployed” persons indistinguishable in any obvious way from those on work relief were still unemployed. If there were plenty of private jobs to be had, why wouldn’t they snap them up? Based on this and other salient facts, and a painstaking econometric test of Darby’s hypothesis, Kesselman and Savin conclude that, had workers employed by New Deal programs been thrown onto the labor market, few if any would have found gainful employment elsewhere. It follows that the BLS’s “uncorrected” unemployment numbers, intended to measure the lack of what Stanley Lebergott, their compiler, called “regular” work, supply a more accurate picture of the progress of recovery than Darby’s corrected series.

Darby’s intention, by the way, wasn’t to show that the New Deal was more successful than conventional statistics suggest. It was to claim that the New Classical view that unemployment is generally voluntary held even for the Great Depression: once the shock of the Great [monetary] Contraction had run its course, Darby claims, unemployment was bound to fall rapidly to its “natural” level as a matter of course, New Deal or no New Deal. New Deal programs merely served to obscure this naturally rapid recovery by supplying workers with more attractive jobs than the ones private employers would have been able to give them. I don’t buy this argument against the New Deal for a minute, both because I think some New Deal steps aided recovery (mainly by encouraging a revival of spending) and because I think others hindered it. But I also don’t find Darby’s numbers helpful in any other way for assessing the New Deal’s success.

The Course of Output

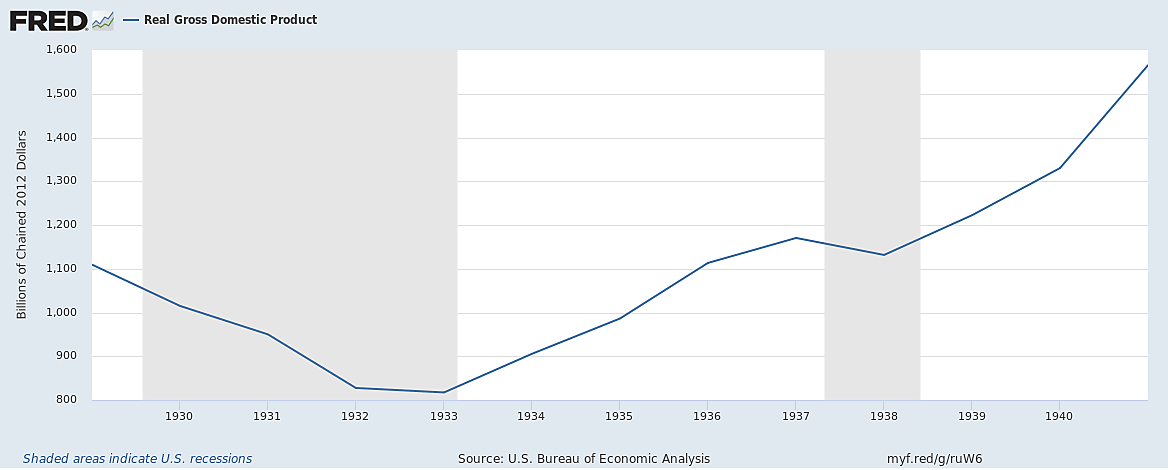

To switch now to looking at the course of real output, the picture here seems at first glance to put the New Deal in a much more favorable light. Here, for example, is what happened to real GDP:

Evidently, real output had returned to its pre-depression level by 1936 and, despite a serious setback in 1937–8, ultimately surpassed it.

But here again the statistics must be handled with care. Healthy economies grow; so a mere return of output to its starting level, or a little above it, after a decade is itself no great achievement. A better measure of the speed of recovery is the time it takes for output to return to its pre-crisis trend line, and in this instance that didn’t happen until 1942, after the New Deal had been cast aside for the sake of mobilization, setting-off what Hugh Rockoff calls a munitions-based “gold rush.”

More fundamentally, what matters isn’t the absolute level of output, but how the progress of actual output compares to that of potential output. That unemployment was persistently high itself tells us that output could have improved considerably more than it did. “The Depression years,” Alexander Field reports, “were disastrous from the standpoint of capacity utilization. …Double digit unemployment for more than a decade represented a terrible waste of human and other resources.” And it wasn’t just labor that was wasted: machines and all sorts of other inputs were also left idle. “The private sector capital stock,” Field says, also remained “in the aggregate, basically unchanged.”

So how could output have recovered as it did? The answer, Field says, is that, despite the depression, the 1930s witnessed remarkable improvements in total factor productivity (TFP)—that is, the amount of real output the U.S. economy was able to squeeze out of any given amount of land, labor, and capital:

Since private sector input growth was effectively absent, all of the growth in output was on account of TFP advance. And since there was virtually no capital deepening, almost all of the growth in output per hour (labour productivity) can also be attributed to TFP growth.

Just why did productivity grow so rapidly during the 30s? While the New Deal may well have contributed to the gains, according to Field its contribution—mainly through the Public Work Authority’s construction of streets and highways—was quite limited. Instead, he says, the coincidence of depression and TFP gains was mostly serendipitous: the harvest was mainly a result, not of anything that happened in the 30s, but of seeds sown by inventors and investors during the previous two decades.

To summarize: if we want to properly gauge the progress of economic recovery after any collapse, we can’t simply look at the number of persons employed, or the amount of stuff being produced. We have to ask, “how close is the economy to making full use of its valuable resources, including its labor force? How close is it to achieving its full potential?” And if we ask that question of the U.S. economy in 1939, as the New Deal neared its end, the answer must be, “Not very close at all.”

The International Picture

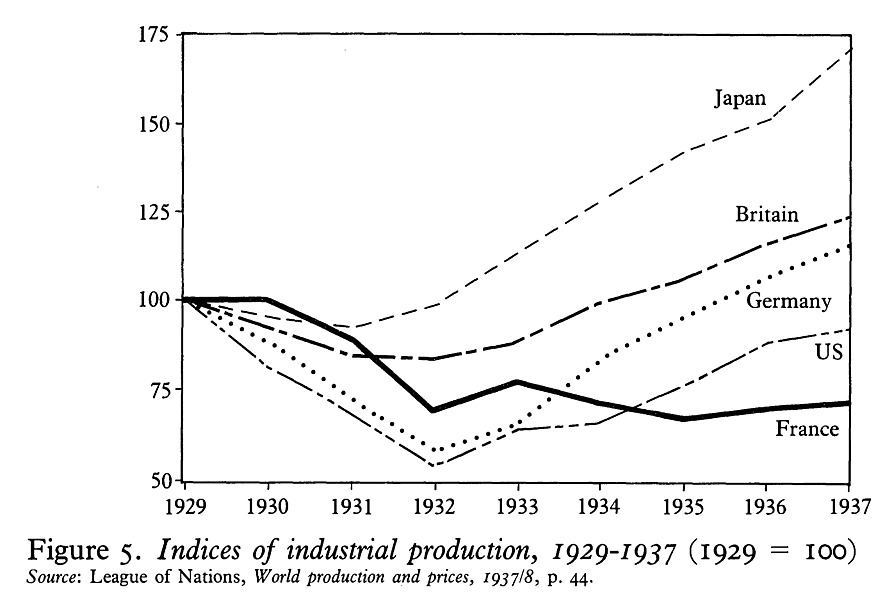

Another way in which to judge the progress of the U.S. recovery is by comparing it with those of other nations. The Great Depression was an international depression, after all. Were the New Deal conducive to recovery, one might expect the U.S. recovery to have matched if not surpassed that of other afflicted nations. Yet, as the chart below, from Barry Eichengreen’s Golden Fetters, shows, despite the rapid productivity growth it enjoyed, by 1937 the United States’ index of industrial production was still below its 1929 level, having grown relatively slowly, and in fits and spurts, since 1932. In contrast the indexes of several other European nations increased steadily, surpassing their pre-depression levels. France alone lagged even further behind than the U.S.

Eichengreen’s chart only goes up to 1937. Here’s another chart, from a French Wikipedia article (hence the French labels: note that “E‑U” stands for “États-Unis,” not “European Union”). This one shows the progress of real GDP (the data are Angus Maddison’s) through 1939. It also differs by excluding the data for Germany and adding those for the U.S.S.R. (ditto) and Italy. According to it, by the end of New Deal, the U.S. was tied with France for last place.

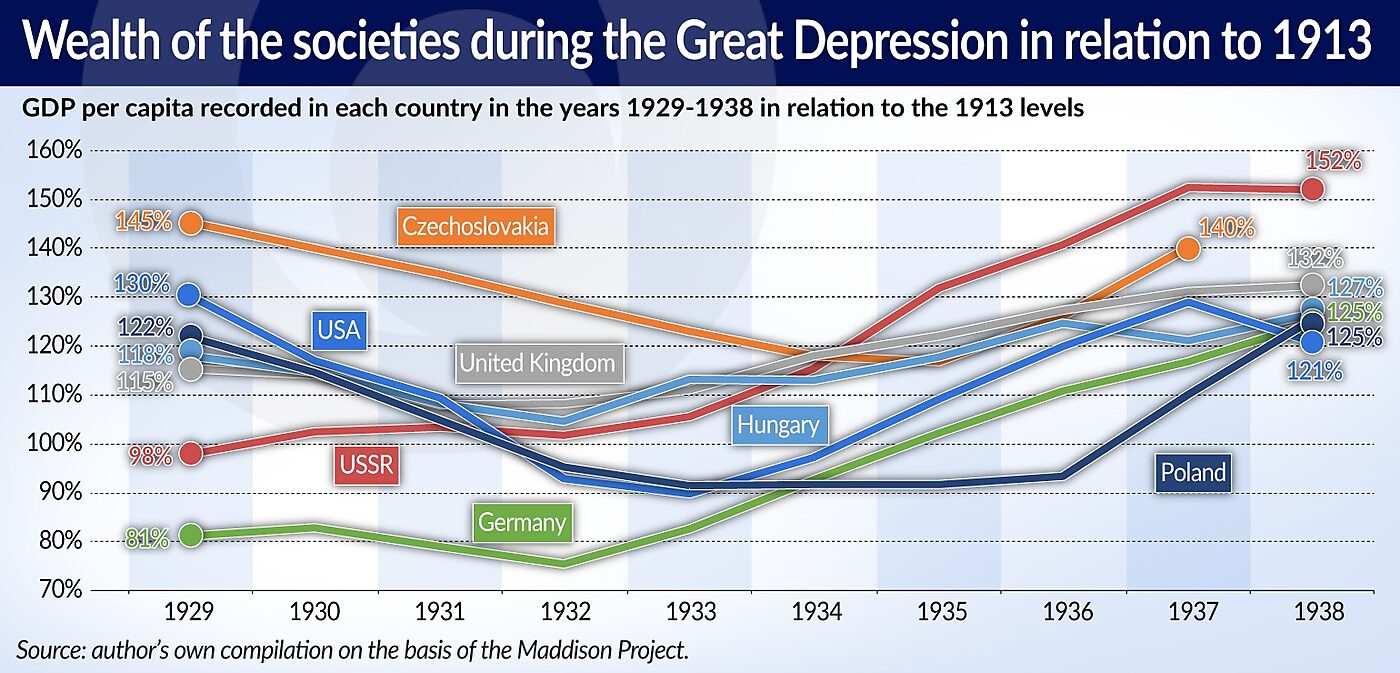

Finally, here’s a third chart, made by Piotr Arak also using Angus Maddison’s data, showing the progress of per-capita real GDP, relative to pre-WWI levels, in the U.S. and six other nations, including several Central European nations that were especially hard-hit by the depression, between 1929 and 1938:

According to this chart, the average U.S. citizen was 30 percent better off in 1929 than in 1913—a postwar gain second only to Czechoslovakia’s, where per-capita income had risen by 45 percent. By 1938, however, the average American was only 21 percent richer than in 1913, making the United States’ record the worst of the bunch.

***

Perhaps, after seeing me run through these statistics, you’re expecting me to add, “ergo, the New Deal was a flop.” But I know better than that. To make the case that the New Deal failed, I need to convince you, not only that it didn’t bring recovery, but that a different set of policies might well have done so. And that’s why this series is only just getting started.