The Congressional Budget Office, as part of The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2017 to 2027, has just released fiscal projections for the next 10 years.

This happens twice every year. As part of this biannual exercise, I regularly (most recently here and here) dig through the data and highlight the most relevant numbers.

Let’s repeat that process. Here’s what you need to know from CBO’s new report.

- Under current law, tax revenues over the next 10 years are projected to grow by an average of 4.2 percent each year.

- If left on autopilot, the burden of government spending will rise by an average of 5.2 percent each year.

- If that happens, the federal budget will consume 23.4 percent of economic output in 2027 compared to 20.7 percent of GDP in 2017.

- Under that do-nothing scenario, the budget deficits jumps to $1.4 trillion by 2027.

But what happens if there is a modest bit of spending restraint? What if politicians decide to comply with my Golden Rule and limit how fast the budget grows every year?

This shouldn’t be too difficult.

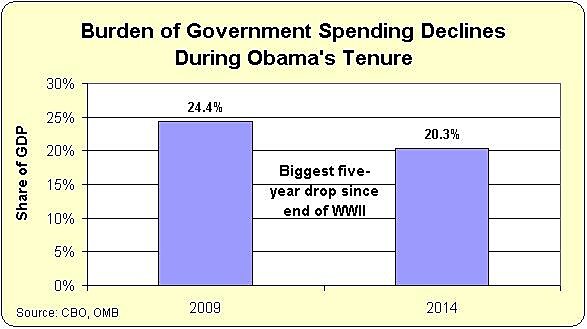

After all, even with Obama in the White House, there was a de facto spending freeze between 2009–2014. In other words, all the fights over debt limits, sequesters, and shutdowns actually yielded good results.

So if the Republicans who now control Washington are serious about protecting the interests of taxpayers, it should be relatively simple for them to adopt good fiscal policy.

And if GOPers actually decide to do the right thing, the grim numbers in the CBO’s new report quickly turn positive.

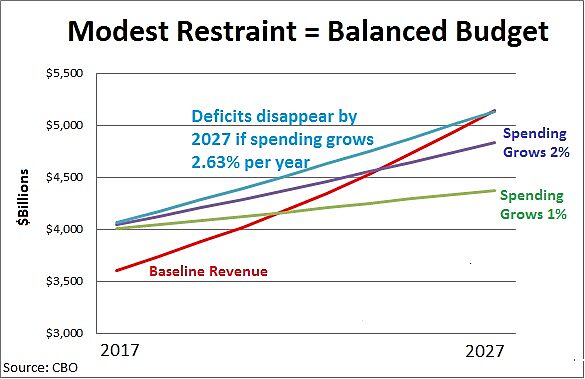

- If spending is frozen at 2017 levels, there’s a budget surplus by 2021.

- If spending is allowed to grow 1 percent annually, there’s a budget surplus by 2022.

- If spending is allowed to grow 2 percent annually, there’s a budget surplus by 2025.

- If spending is allowed to grow 2.63 percent annually, the budget is balanced in 10 years.

- With 2.63 percent spending growth, the burden of government spending drops to 18.4 percent of GDP by 2027.

To put all these numbers in context, inflation is supposed to average about 2 percent annually over the next decade.

Here’s a chart showing the overall fiscal impact of modest spending restraint.

By the way, it’s worth pointing out that the primary objective of good fiscal policy should be reducing the burden of government spending, not balancing the budget. However, if you address the disease of excessive spending, you automatically eliminate the symptom of red ink.

For more background information, here’s a video I narrated on this topic. It was released in 2010, so the numbers have changed, but the analysis is still spot on.

P.S. Achieving good fiscal policy obviously becomes much more difficult if Republicans in Washington decide to embark on a foolish crusade to expand the federal government’s role in infrastructure.

P.P.S. Achieving good fiscal policy obviously becomes much more difficult if Republicans in Washington decide to leave entitlement programs on autopilot.