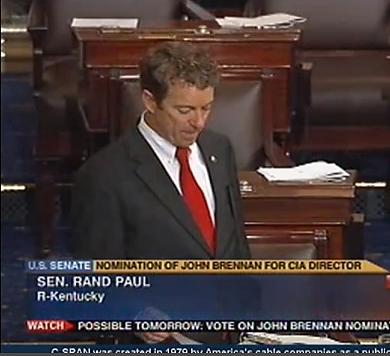

As Sen. Rand Paul acknowledged early on in his epic 13-hour speech Wednesday (highlights here), his decision to mount an old-fashioned, talk-till-you-drop filibuster of John Brennan’s confirmation as CIA director didn’t really have much to do with Brennan personally. But neither was it really, at a fundamental level, about the narrow question of whether the president can “drop a Hellfire missile on your cafe experience” as you sit sipping a latte on American soil. If any citizens were realistically worried about that prospect, Attorney General Eric Holder has (somewhat belatedly) answered that question in the negative, prompting Paul to declare victory on that front.

But as Wired’s Spencer Ackerman observes, the spectre of Predators over Starbucks actually served to spotlight the “extraordinary breadth of the legal claims that undergird the boundless, 11-plus-year ‘war on terrorism’ ”—and to frame a much broader and more wide-ranging critique of that “perpetual war,” in which Paul charged that Congress has abdicated its responsibilities to an unaccountable executive branch. In Paul’s view, “we shouldn’t be asking [the president] for drone memos”—documents laying out the legal basis for the CIA’s targeted killing program, which the administration has finally, grudgingly deigned to provide to Congress, though not the American public—“we should be giving him drone memos.” As if to highlight the erosion of statutory checks on the president’s counterterror authority, Sen. Lindsey Graham declared that, after all, the Authorization for the Use of Military Force passed after 9/11 made no exception for actions “in the United States”—even though Congress had specifically rejected a request to include that phrase in the authorization.

The broadly positive reaction to Paul’s filibuster suggests, to me at least, that many Americans now fall outside the bipartisan Washington consensus that there’s little need for serious congressional scrutiny or debate when it comes to the War on Terror, and are relieved to hear that dissatisfaction echoed on the Senate floor. No longer as terrorized or shell-shocked as we were a decade ago, perhaps we’re becoming less willing to accept assertions that the public has no business knowing how and when the president may authorize secret killings in countries where we are not formally at war. If we want to get really radical, we may eventually begin to suggest there are proper constraints—if not constitutional, then at least moral—even on the killing of human beings who had the poor taste to be born in another country. We might question whether Americans are being well served when Congress spends less time debating the reauthorization of the Patriot Act or the FISA Amendments Act than Senator Paul did (literally) standing on principle Wednesday night.

Is it absurd to fear, as some of Paul’s colleagues charged, that the president will begin launching drone strikes on American soil? Probably. But the point is precisely that we live under an administration so unwilling to acknowledge meaningful limits on what they may do in the name of national security that it was an exercise in tooth-pulling just to get a public disavowal of an absurd scenario that the government’s anemic targeted killing “standards,” taken to their logical extreme, would not appear to foreclose. The crucial message we should take from Paul’s marathon oration, then, may be this: If it’s absurd to pose the question that inspired his filibuster, surely it’s far more absurd that we’ve arrived, after a decade of complacency about government secrecy and unfettered executive discretion in the sphere of counterterrorism, at a point where the question would need to be posed.