Last week was a significant one for housing finance policy, as the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau gathered input on how to reform the underwriting rules that mortgage lenders must follow. With $15 trillion of mortgage debt outstanding, this is a subject of great economic significance for the U.S. economy. Unsurprisingly given the high stakes, it is also a contentious subject on which some of the largest trade and activist groups in Washington — from banks and Realtors to community groups and public-interest lawyers — have weighed. I too submitted a comment letter on behalf of the Cato Institute.

The auspicious news is that the CFPB has announced the expiration of a damaging loophole that has increased risk in mortgage finance. In her decision, CFPB Director Kathy Kraninger enjoyed the support of Mark Calabria, who as head of the Federal Housing Finance Agency is responsible for prudential standards at Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and the Federal Home Loan Banks. In this way, Kraninger and Calabria can help both consumer protectionandfinancial stability. The comment letters focused on what, if anything, should replace this loophole.

The regulations the CFPB seeks to update came into effect in 2014. As is well-known, the financial crisis caused a great deal of distress, with up to ten million American families losing their homes to foreclosure. Most of these people had borrowed unprecedented amounts for housing in which they had little equity. High mortgage payments relative to incomes meant that, absent continued price appreciation, these new buyers might soon find themselves unable to keep up. A great deal of blame for their plight belongs with Fannie and Freddie, two government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) that, thanks to their dominance of the secondary mortgage market and the prodding of politicians, led a steady decline in underwriting standards that ended in tragedy. Part of the legacy of the crisis was the giant bailout of Fannie and Freddie, which the Congressional Budget Office estimates left U.S. taxpayers $300 billion worse off.

Thus, it was a surprise that, when the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau crafted new rules for mortgage underwriting in 2013, it carved out an exemption for Fannie and Freddie from the general conditions applying to qualified mortgages (QMs), so called because they are meant to have features that make them unlikely to default. Whereas non-GSE QMs couldn’t exceed a limit on monthly debt payments of 43 percent of the borrower’s gross income in order to benefit from the QM safe harbor, GSE mortgages could. This debt-to-income (DTI) ratio matters because it predicts default, especially in times of stress like the 2008 crisis. Along with the borrower’s credit history, the loan amount relative to the price of the home, and other factors such as monthly cash flow, DTI ratios form part of a common suite of loan underwriting measures.

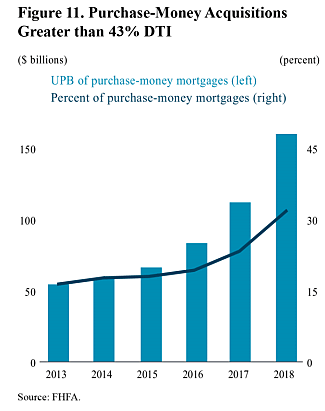

Despite the significance of DTI, the CFPB made Fannie and Freddie exempt from its post-crisis DTI limit, creating the loophole known as the “GSE patch” or “QM patch.” Since the patch came into effect five years ago, lenders have dished out high-DTI mortgages at a rising pace, safe in the knowledge that Fannie and Freddie — by now in government “conservatorship” — would buy them. Sure enough, the GSEs obliged, so that — as the chart below listing Fannie and Freddie mortgage acquisitions shows — an increasing share of the loans they buy from lenders have been high-DTI loans.

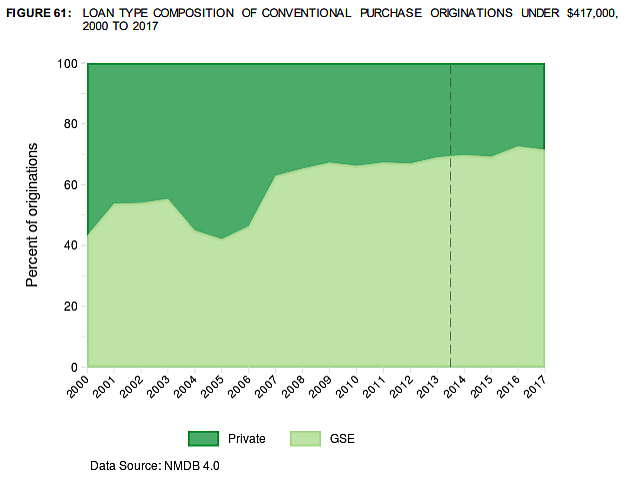

The problems with the patch are several and grave. First, by the CFPB’s own reckoning, mortgages issued under the patch are more likely to go delinquent than similar loans the GSEs cannot purchase because the loans are larger. This disparity in loan performance did not exist before the patch came into effect. Not for the first time, the opportunity to sell loans to a taxpayer-backed entity seems to have caused poorer underwriting standards. Privileging the GSEs has not only devalued the quality of Fannie and Freddie’s portfolio, but also increased their role in housing finance. As the chart below shows, Fannie and Freddie have grown the share of loans they buy since 2014. That contradicts a key goal of the Trump Administration — namely, to shrink the size of what remain fragile and systemically important institutions. It is also highly imprudent, given the lessons from 2008 about the dangers of a government duopoly.

The patch has also prevented a liquid market for non-QM mortgages from emerging. The CFPB’s intent in creating the QM was to give presumption of compliance to mortgages that, by meeting strict criteria, were unlikely to default early. All other mortgages would be subject to comprehensive underwriting by lenders. But the patch has created a loophole for riskier mortgages to eschew such underwriting. Even at its birth, the patch was a poor remedy to an ailing housing market. Now that the economy is booming, it has become unjustifiable.

Fortunately, the CFPB has announced it will let the patch expire as originally intended on January 20, 2021 or on the GSEs’ exit from conservatorship — whichever comes first.

But Kraninger shouldn’t stop there. The 2013 regulations created potentially unlimited lender liability for mortgages that do not meet the QM safe harbor. Unsurprisingly, such a draconian policy has chilled the market for non-QM loans. While the patch is in place, lenders have little incentive to push for changes to the QM standard, since they can avoid its most onerous burdens by directing their originations toward Fannie and Freddie. Now that the patch will expire, the need for an alternative standard is urgent.

With that in mind, the CFPB should afford QM protection to every mortgage that hasn’t gone delinquent within two years of origination. This will reconcile the Bureau’s objective of minimizing early delinquencies with a reasonable standard for liability that doesn’t chase lenders away from the mortgage market in fear of future litigation. There might be certain exceptions from the safe harbor for mortgages with non-standard terms such as high fees, variable rates, or balloon payments. But, in general, loan defaults that occur long after origination are not the consequence of poor underwriting but changes in the economy or the borrower’s own circumstances. Regulation must acknowledge that.

The CFPB should keep a 43 percent maximum debt-to-income ratio for loans that are QMs from the point of origination. That contradicts the view of some lenders, real estate agents, and think tanks who argue that an interest-rate variable should replace the DTI ratio. In a competitive market, their argument might be sound: interest rates summarize all the information that individual factors such as DTI supply regarding the borrower’s credit risk. The higher the interest rate, the greater the chance of non-repayment (other things equal). But our government-supported, duopolistic housing finance system blunts the predictive power of interest rates because low-risk borrowers subsidize high-risk borrowers. In that context, DTI is superior to interest rates.

Furthermore, the most common proposal for an interest-rate substitute for DTI (the Average Prime Offered Rate, plus 200 basis points) would substantially raise the share of Qualified Mortgages with early delinquencies, according to its proponents’ own data. In a distressed environment, that share will likely only go up.

In their effort to reduce the extent of taxpayer support for the mortgage market, Directors Kraninger and Calabria face formidable opposition from interest groups who benefit from greater lending volumes, looser underwriting, and the continued government management of Fannie and Freddie. Yet they must not waver, because avoiding a repetition of the last housing crash hinges on stopping public policy from promoting risk and unsound lending. The GSE patch’s expiration is a good start.

You can read Diego Zuluaga’s full submission to the CFPB here.